Assignment 1.3: Summary of Chamberlin’s Final Chapter

J. Edward Chamberlin’s If This Is Your Land, Where Are Your Stories?: Finding Common Ground closes with a poignant chapter titled “Ceremonies.” In the final chapter, the book as a whole is tied together, and three of Chamberlin’s essential points stand out to me. He emphasizes the importance of building understanding between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people in Canada through the power of stories, calls attention to the paradoxical nature of stories and the contradictions they weave, and asserts his belief that we should (and we can!) return “underlying title” to aboriginal title. Finally, Chamberlin brings these ideas together to assert an answer to his titular question, resolving that our stories lie on “on common ground” (240).

Canada is a nation marked by the history of settler-colonialism, but Chamberlin believes that through the transformative power of stories on relationships and understanding, the Indigenous people of Canada can finally have justice and reclaim a sense of unsettled home on this stolen land. While we cannot change the past or erase the violence inflicted by settler-colonialists, Chamberlin maintains that “we can replace the theatre of desecration with the theatre of a decent burial” (233). Throughout the book, Chamberlin ruminates on the power of stories as “ceremonies of belief” that carry important messages of who we are and where we belong, and importantly, emphasizes how misunderstanding the stories of others can lead to and exacerbate conflict. This has been seen time and again when the stories of the First Nations and Inuit people clash with the stories of settlers. Chamberlin believes that Canada can write a story for all of us, “of natives and newcomers,” that has something to “offer the world” when, through this role, our country steps into the role of a peacemaker and mediator (228).

Part of the power of stories arises from their paradoxical nature. To understand someone else’s story or their relationship to it, one must accept and explore the contradictions inherent in stories. Chamberlin describes a myriad number of “contradictory truths” that manifest in stories: sense and nonsense, truth and fiction, reality and imagination, mystery and clarity. At the borders between these ideas, liminal spaces are created. We should not avoid or ignore these spaces due to fear of contradiction or fear of disrupting our firmly held beliefs about ourselves and others; these are the areas where we may begin to explore our relationship to those different than us so to begin moving beyond a black and white understanding of “Them and Us” (223). Accepting contradictions means we might believe and not believe our own stories or the stories of others. In this manner of thinking, we might hold our own beliefs while not discrediting the belief of someone different than us. Chamberlin makes clear that just as there is a difference between sense and nonsense, there is still a difference between Them and Us, but that the difference becomes transformed by our shared value in ceremonies of belief (224). We do not need to believe in stories that are not our own, but we must understand the importance of believing, and see their faith in their stories; “We need to understand because our lives depend on it” (224).

Chamberlin makes the bold assertion that Crown land should be reverted in title to Indigenous land. He hopes that this change might “finally provide a constitutional ceremony of belief in the humanity of aboriginal peoples” (231). However, Chamberlin makes a controversial point when he argues that changing the title would be legally easy, but wouldn’t truly change anything. He maintains that what is needed to create change is an understanding of stories and ceremonies, and a recognition of our own stories being equally important and real to the stories of others. I was uncomfortable with Chamberlin’s word choice in stating that changing the underlying title back to Indigenous title would be an “aboriginal ‘trick'” (229). He says “we’ll get used to it” and “it will still be a metaphor” (233). A shift in ideology is important; however, I believe an underlying change must be matched by a radical shift in perspective on the surface as well.

I continue to question whether I agree with Chamberlin’s final answer to “if this is your land, where are your stories?” I cannot agree that this land is truly “common ground” in a literal sense. But I understand his metaphor of our need to discover shared interests and create understanding between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Canadians. I will continue to explore these ideas and seek to better understand my own position.

Works Cited

Chamberlin, J. Edward. If This Is Your Land, Where Are Your Stories?: Finding Common Ground. Vintage Canada, 2004.

“City of Winnipeg Moves Forward on Policy for Changing Potentially Offensive Names of Monuments, Places | CBC News.” CBCnews, CBC/Radio Canada, 15 Jan. 2020, www.cbc.ca/news/canada/manitoba/winnipeg-renaming-reconciliation-1.5426498.

Silberman, Raylon. “Pine Ridge: The Three Stages of Liminality.” Indigenous Religious Traditions, 14 Oct. 2014, sites.coloradocollege.edu/indigenoustraditions/•-ceremonial-reflections/pine-ridge-the-three-stages-of-liminality/.

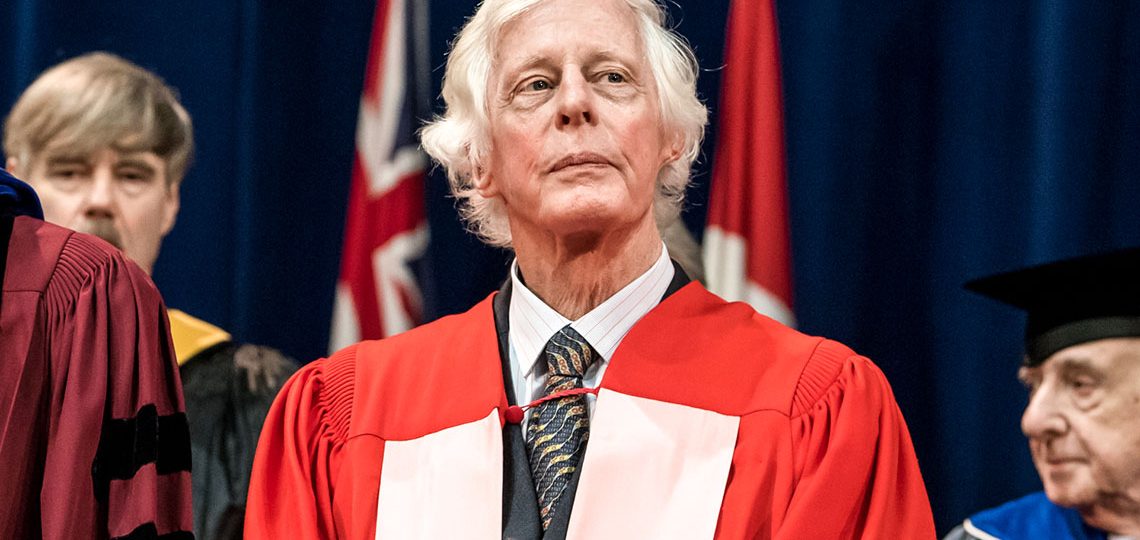

Steve Frost. “Scholar, author and Indigenous rights advocate Edward Chamberlin receives U of T honorary degree.” U of T News, UToronto, 13, June 2013, https://www.utoronto.ca/news/scholar-author-and-indigenous-rights-advocate-edward-chamberlin-receives-u-t-honorary-degree.

Tuck, Eve, and K. Wayne Yang. “Decolonization Is Not a Metaphor.” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, vol. 1, no. 1, 8 Sept. 2012, pp. 1–40., https://jps.library.utoronto.ca/index.php/des/article/view/18630.

Thank you Georgia – I’m sending you out a comment sheet this morning, just wanted to stop to let you know I appreciate your insightful reading.

Thank you so much, Erika! I really appreciated your comment sheet. I’m really enjoying looking critically at my sense of home and of the power of stories in creating my sense of identity.