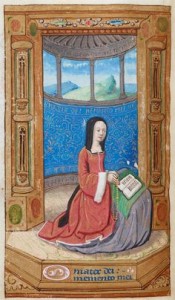

Considered the most popular book in the Middle Ages, the Book of Hours offered the reader “an intimate conversation with one of the most important people in his or her life: the Virgin Mary” (Wieck 27). While its design was based on the breviaries used by the clergy, the book’s target audience was the laity. It is composed of several divine offices dedicated to the daily performance of prayers and meditation, which would be read several times a day. Due to this constant use, books of hours were generally small and portable. According to Albert Derolez, the height of most books of hours are usually between 8 to 23 cms (85). Certain exceptions, however, can be found, such as the Duke of Berry’s Très Riches Heures, which is considered the largest version made for a Book of Hours.The portability and personal use of a religious book marked a shift in pious practices, bringing public devotion into the private sphere. Nonetheless, as Roger S. Wieck ascertains, “Medieval piety incorporated a substantial element of public display” (34). Thus, books of hours were also considered items of status, which could be exhibited as a symbol of elevated piety in public settings.

Books of Hours became especially popular with the rise of the cult of Mary; the Hours of the Virgin, the first office contained in Books of Hours, was the primary focus of this cult (Wieck 27). According to the Oxford Companion to the Book,

The Hours of the Virgin perhaps originated as early as the mid-8th century, and was established by the 10th century as an abbreviated version of the Divine Office for monks and canons. During the 12th century the text gained popularity with a broader audience, including lay men and women, when it was often attached to the psalter, then the most popular type of book for lay devotions.

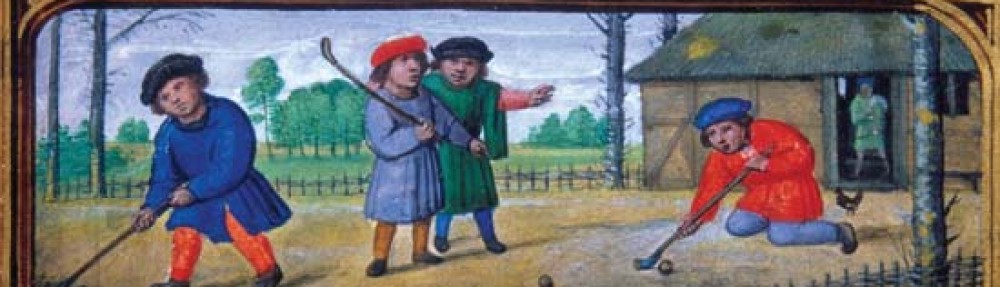

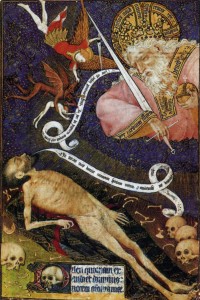

Kathleen E. Kennedy similarly comments on the how readers highly regarded their copies, stating that “[w]ith a Book of Hours the devotee prayed to Mary and the saints as personal heavenly intercessors, and the book itself could act as a sort of virtual shrine, including, by means of the Office of the Dead, the departed members of the devotee’s family and community” (694). In addition to the Hours of the Virgin, the Book of Hours were composed of a calendar, four gospel lessons, the hours of the cross, the hours of the holy spirit, two prayers to the Virgin known as “Obsecro-te” and “O Intemerata,” the Penitential Psalms and Litany, Suffrages, and an Office of the Dead (Wieck 27). Some calendars displayed illustrations of the seasons of the year and rural works connected to them.

The Hours of the Virgin are composed of eight sections:

- Matin and Lauds – daybreak

- Prime – 6 am

- Terce – 9 am

- Sext – noon

- None – 3 pm

- Vespers – sunset

- Compline – evening

These follow the clergy’s canonical hours (Wieck 28).

Differently from religious books served for instruction, books of hours “were intended to be held in the hand and admired for their delicate illumination rather than put on a library shelf and used for their text” (De Hamel 168). Being more than just a religious text, the book of hours was also an object of art and piety. Commenting on this artistic value of these books, Virginia Reinburg argues that in certain cases, a “book of hours itself may have served as a kind of amulet: an object to be worn or held or touched as much as read” (237). In many ways these books were also perceived as family treasures, which could be passed down by mothers to daughters (Wieck 28). Reinburg also discusses the physical value of these books, stating that

Women considered their books of hours intimate possessions, objects to be passed down as a precious legacy to daughters, goddaughters, and dearest friends. Patterns of gift giving and inheritance show this. To be sure, women sometimes gave books of hours to men, often sons or sons-in law. And men gave books to the women in their lives, usually their wives and daughters. But gifts among women were special: they wove webs of reciprocity, in which prayers and prayer books were signs of affection and enduring relationship. (237)

The introduction of Books of Hours also promoted a larger participation of women in religious practices. While men could also possess these books, their majority of their owners were women. Reinburg discusses the impact of female readership in the production and circulation of books of hours, explaining how

some booksellers’ inventories from the sixteenth century list dozens of copies of printed ‘hours for the use of women,’ suggesting that there were books of hours meant specifically for women. Books are also on occasion described as ‘woman’s book of hours’ in inventories after death, perhaps a reference to the embellished bindings and covers women crafted for what they sometimes called ‘my best prayer book.’ (236)

This care of their books clearly signals how women perceived these books as not solely a text to be read, but also as a valuable object of devotion.

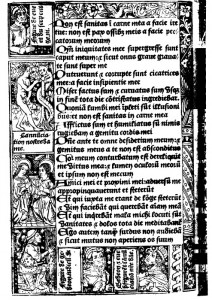

Due to this unusual physical significance attributed to these books, many scholars have been interested in investigating reading practices linked to these works. Art historians are likewise interested in Books of Hours. Since it was initially an extremely deluxe item, early book of hours are specially made for their patrons, often containing their portraits or coats of arms in illustrations (Wieck 30).As literacy and the popularity of this book grew within the laity, the demand for inexpensive books of hours increased, causing more lavish versions of the book to be produced (Wieck 33). With the advent of press, a variety of versions of books of hours were produced containing illustrations made with woodcutting. Mary Beth Winn estimates that “more than 1600 printed editions of Hours were produced before 1530, ninety per cent of them in France” (177).

As Books of Hours arrived in England, they started to be called “primers.” Nicholas Orme comments on the use of the term, saying that “rather confusingly, it seems to have been applied to both books of basic prayers and to books of hours” (695). As the name implies, along with being a text dedicated to devotion, these books could also be used as a literacy tool in the teaching of children (Orme 248-9). Reading was, indeed, considered an important aspect of piety which was significantly linked to one’s connection to God. Laura Sterponi comments on this aspect of reading, as she affirms,

The characterization of reading as a devotional activity and its close link with meditation and prayer is also manifest in the practice of lectio divina. Literally translated, lectio divina means ‘divine reading’ […] Lectio divina has been a central activity of monastic life since the founding of Western monasticism (fifth century) to the late medieval period, when it also became popular among the laity. Lectio divina was conceived of as a primary instrument for individual reformation, designed to progressively liberate the practitioner of vice, shape virtuous habits, and guide her to spiritual illumination. (671)

While the majority of the laity was not fluent in Latin, the oral repetition of the psalms during mass enabled them to understand their meaning while reading them at home. With the rise of Lollards in England, many books of hours started to be translated into English, making the material more accessible to readers. Although we no longer make use of Books of Hours nowadays, some of their illuminations can still be found in Christmas cards.