This section contains information on the University of British Columbia’s exemplar of the Book of Hours (Use of Rouen) – A Link to its Reference Page can be found HERE and a link to its digitized format can be found HERE. Please refer to the subsections “Contents” and “Codicological and Paleographical Information” for more technical details about our exemplar.

Being one of UBC’s most precious acquisitions, our Book of Hours has joined the library’s Western Manuscripts and Early Modern Texts in the beginning of 2016. While little is known about its provenance, documentation signals that the manuscript was created circa 1430-40, for the use of Rouen, France. According to the Sotheby’s auction information, “[t]he style of illumination, the miniature of St. Romanus, bishop of Rouen (who also appears in red in the calendar), and the Use of the Hours of the Virgin, all point to the book’s origin in Rouen.” Containing 108 pages, the book was commissioned by a French woman, whose likeness appears in the last illumination of the work next to the figure of the Virgin and baby Jesus (f.99v).

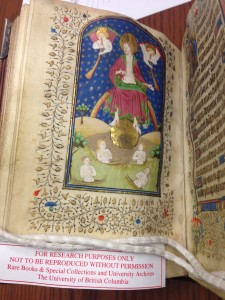

Its six illuminations were likely created by the Fastolf Master and members of his atelier, whose name came from a manuscript produced for Sir John Fastolf in 1450. He moved to Rouen in 1420, after mastering his craft in Paris. Being near the centre of the English administration, he obtained several English clients. He left Rouen in 1449 in order to settle in London (Sothebys).

The book was rebound in the 19th century, when it acquired its current faux-medieval brown leather binding with metal fittings.

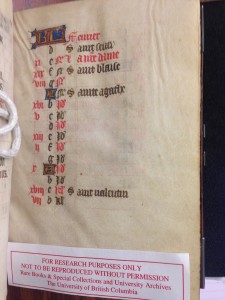

As usual in Books of Hours, our exemplar begins with a calendar containing dates of Saint’s days and Feast Days:

In contrast with the rest of the book, the calendar is in French. It contains six lined columns with 16 lines each, and its text is written in black and red with various decorated initials. According to Christopher De Hamel, it was customary to write “ordinary” saints’ days in black ink and special feasts in red ink (this custom is also responsible for the creation of the expression “red-letter day”) (174). This exemplar clearly follows the pattern. Annotations of birthdays and deaths, also customary in the Middle Ages, can be found in our exemplar:

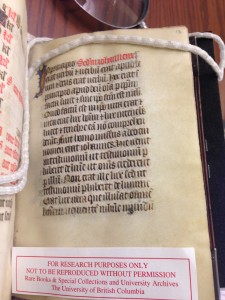

Following the Calendar, one can encounter the Gospels of John, Matthew, and Mark, which contain illuminated initials and golden details throughout the text. Interestingly, all Gospels, with the exception of Matthew, begin with the expression “In illo tempore,” which means “At that time.” One can only wonder why the expression was omitted in Matthew; perhaps the scribe was copying this Gospel from another exemplar? Or perhaps he unintentionally skipped a line? Some other irregularities in Latin can be found in this exemplar which denotes that the scribe was possibly not very familiar with the language.

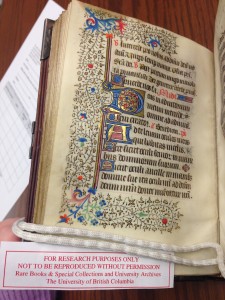

The Gospels are followed by the Hours of the Virgin, which is introduced by an illumination of the Annunciation:

As usual, the Offices begin with the expression “Domine labia mea aperies. Et os meum annunciabit laudem tuam” (“Lord, open thou my lips, and my mouth shall forth thy praise”) (De Hamel 174). This first office contains the hours of the virgin (matin), lauds, suffrages, prime, terce, sext, none, vespers, and compline (Information about specific psalms and the contents of each section can be found in the contents tab). All of the sections begin with highly decorated initials in blue, red, and gold, as well as some border decoration.

This Office is then followed by the Seven Penitential Psalms, which were connected to the salvation of one’s soul. De Hamel argues that most readers of Books of Hours would read them quietly, probably under their breaths (170). Our exemplar contains a singleton (a single page which was not a part of the text’s original gathering), which contains an image of a wounded Christ surrounded by angels. This illumination was used for meditation on the significance of penitence and of Jesus’ sacrifice.

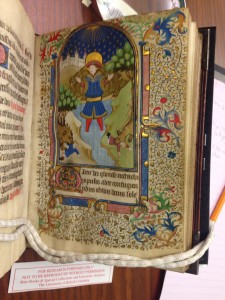

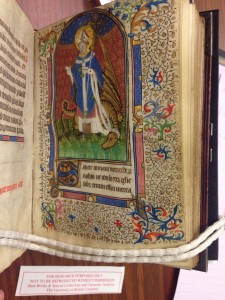

This section is followed by the Litanies, which consisted of a list of saints’ names to whom one would pray. In our exemplar, the name of each saint is introduced by a decorated initial and is followed by the word “Ora” (“Pray”). This section contains the images of St. Eustace (possibly connecting the manuscript to the nearby town of St. Eustache-das-Forêt, where the patron of this book possibly lived (Sotheby)) and of St. Romanus.

After this section, one can find an inserted singleton, which contains a full-page illumination of a funeral service, indicating the beginning of the Office of the Dead (f.66v).

This Office is composed of several Psalms, some of which are repeated from previous sections, which are focused on the idea of dying well. It also comprises three “Nocturne” sections which were read in alternating days of week. Differently from the signs of thorough use on first pages of the manuscript, which contain the Hours of the Virgin, the pages of the Office of the Dead appear to be in pristine conditions, indicating that they were perhaps not usually read by the book’s patron.

Following the Office of the Dead, one can find the Offices of the Holy Cross and of the Holy Spirit. Being optional parts, these offices are not contained in all Books of Hours. The Book then concludes with another series of prayers to the Virgin, where the illumination of the book’s patron (above) can be found. Although annotations are considered rare in books of hours, our exemplar possesses a small notation in French next to this last illumination.