The purpose of modern and renovated buildings are often to support tourism and international business; they do not directly benefit the locals. These create zones of exclusion that allow tourists to access the history and heritage of the region, but do not allow locals to define or interact with it. As a nation built off of colonialism and international influence, social memory is often traded off for a simpler, idealized Cuban experience.

In similar cases around the Caribbean, for example the Mayan Riviera and Puerto Rico’s Caribe Hilton, ‘public’ areas have become exclusive to tourists, where local access has been limited to employment (Morawski, 2014; Manuel-Navarrete & Redclift, 2012).

A Global Phenomenon

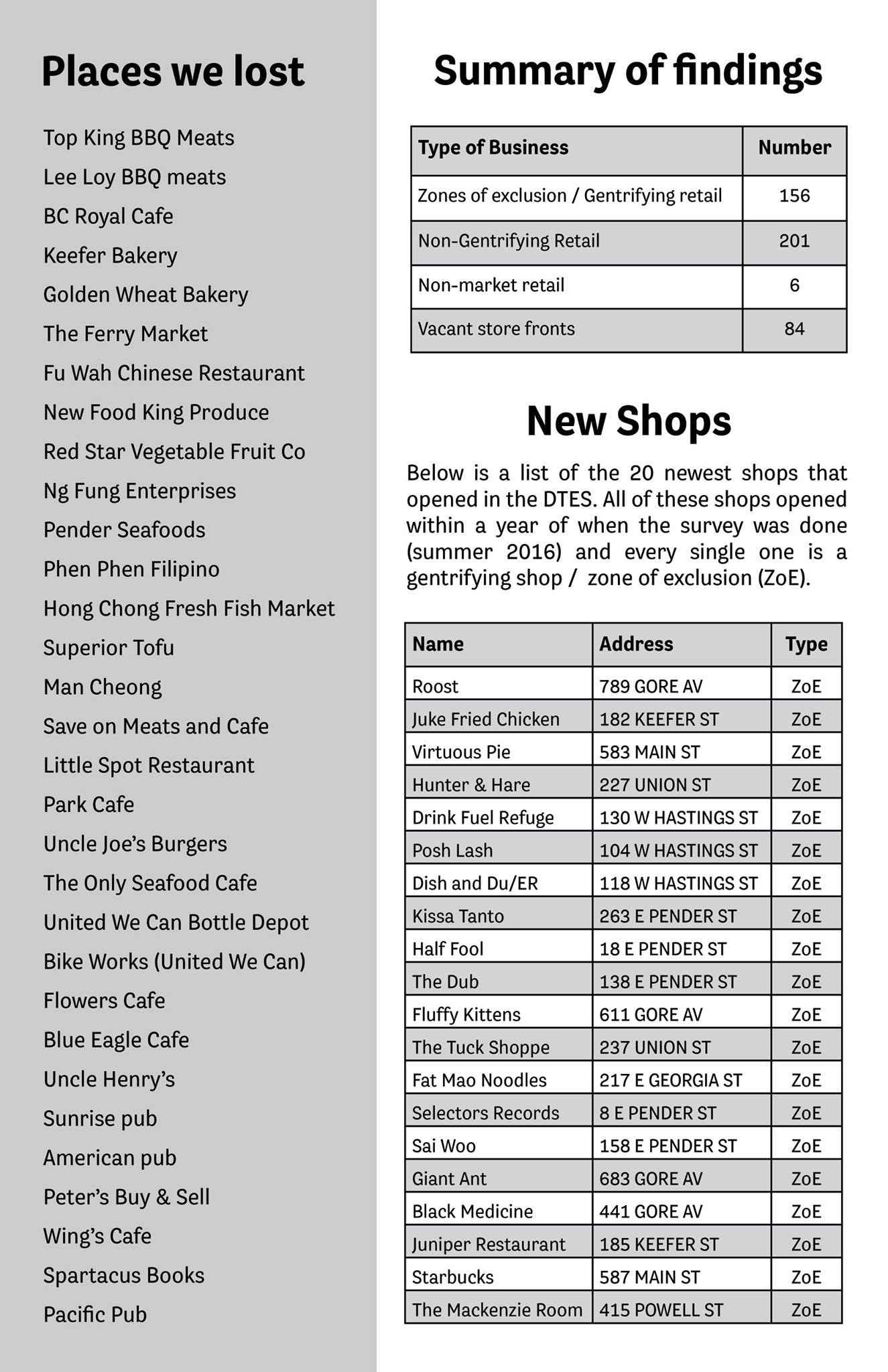

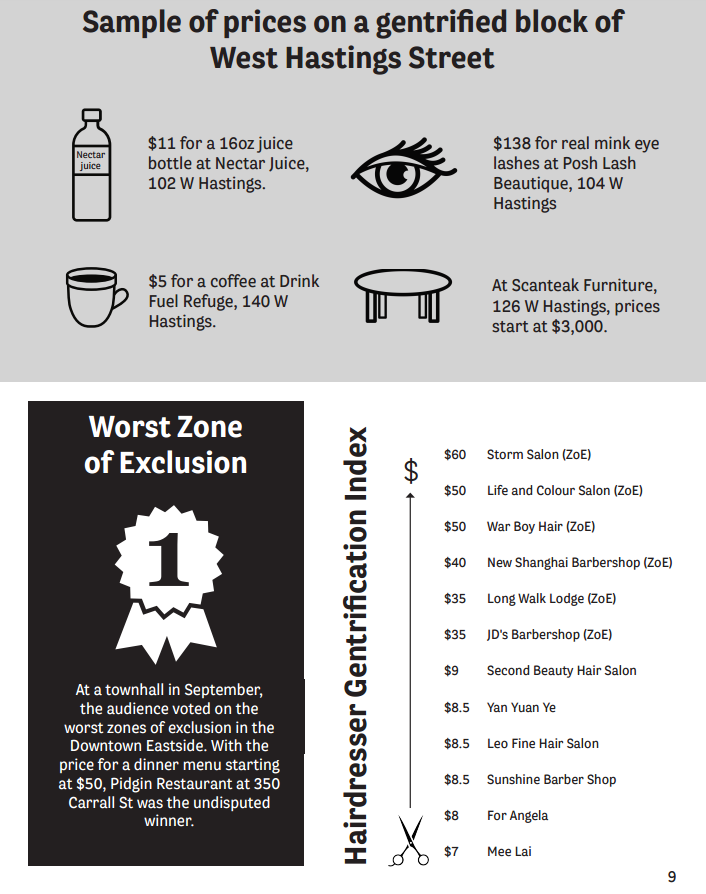

The unintended effects of modernization and the prioritization of tourism has also infiltrated the Global North. This is visible in Vancouver, BC, where gentrification has occurred as a result of rising land value and demand for housing. This is particularly evident in neighbourhoods such as Chinatown and the Downtown Eastside (DTES). These neighborhoods have rich histories and in recent years have been home to low-income locals. However, large scale developers have purchased and rebuilt areas with market-rental condominiums and hip, new businesses and restaurants, pricing out former welfare-rate residents. A recent report released by the Carnegie Community Action Project (2017) mapped the rising cost of local amenities, finding that, in some of the gentrified areas, a bottle of juice cost more than a haircut from a legacy business in Chinatown. Heritage and history has come down to building facades, replacing Chinese seniors with young people, able to afford market condos. Businesses and restaurants adapt to the new clientele, rapidly changing the face of the neighbourhood for economic benefit.

In a Cuban context, heritage areas have adapted to tourist clientele, displacing local businesses for profit, effectively becoming exactly what Castro vowed it would not. By allowing foreign investment and influence to choose the path to heritage preservation, corporations define cubanidad for the locals, rather than allowing them to tell their own stories through their own voices.