Image Source: https://bit.ly/37yN9Oj

HISTORY & BACKGROUND

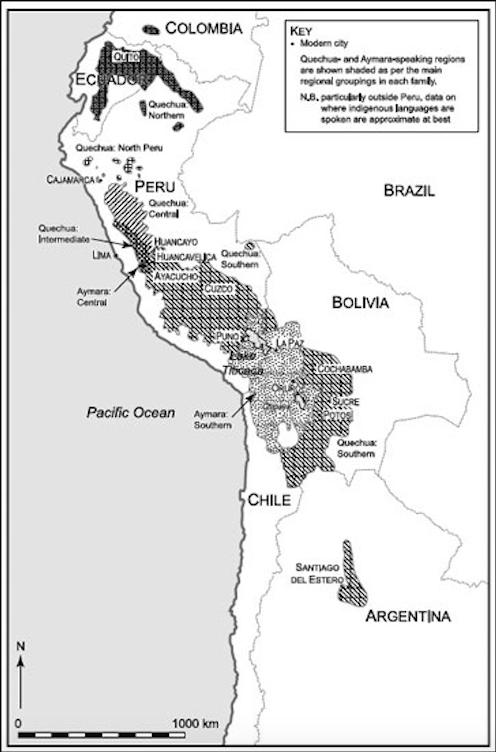

The Uros are a sub-ethnic group belonging to the larger Aymara Indigenous population, which span across Bolivia, Chile and Peru. In order to understand the geographical conditions by which the Uros live, we must first dive into the history of the Aymara, and its multiple divisions over time. The Aymara are presently one of the largest ethnic groups in the Andes amounting to approximately two million inhabitants, and their language, also called Aymara, is the fourth most spoken Indo-American language (after Quechua, K’iche Maya and Guaraní) (Albó, p. 43). Their emergence is dated years before Incan civilization, around 1200 and 1400 AD, in the Andean region of Apurimac in Peru where they built their initial community. The Aymara are known for their adaptation and resilience following a history of migration, which has led the group to be dispersed through the Andes. However, the decision to migrate occurred due to two historical periods: the Inca and the Spanish conquest.

We will begin by talking about the Inca conquest, or the Tahuantinsuyu, where the main goal of the Inca was to create a homogenized Andean community. In order to achieve this, Indigenous communities around the region were brought to Cuzco, the capital and home of the Inca, and separated into small villages called Ayllus, where they were forced to adopt Quechua as their lingua franca and work in subsistence farming for the community (Albó p. 44). Consequently, the Tahuantinsuyu became an environment of cultural exchange during this first conquest, where a large part of Aymara identity was lost and merged with Quechua. Yet, the arrival of the Spanish prompted the Aymara to migrate once again. The Spanish perceived the Inca as a single ethnic group, so they concentrated their conquest efforts mostly around the capital and surrounding areas. Because state borders were incredibly ambiguous during this period, the Aymara were allowed to escape the contested city of Cuzco and fled towards more remote areas across Bolivia, Peru and some of Chile. During this series of migrations, there was a split between the Aymara according to the regions they inhabited: those who arrived in lake Titicaca and Poopo in Puno were the Uros or Pukina, the Aymara remained in Wari and later returned to Cuzco, while those settling in Bolivia called themselves the Uru. Despite having a wide variety of sub-communities and villages, most of these groups still identify themselves as Aymara to this day. The Uros are one of the most prominent divisions of the Aymara, who arrived at Lake Titicaca during the Spanish conquest and purchased it from them, calling themselves the protectors of the lake, which now constitutes a large part of their identity (Albó p. 46).

COSMOLOGY

Due to the cultural exchange that occurred during the Tahuantinsuyu, the Aymara adopted a cosmology that’s very similar to the Quechua, which focuses on the spiritual reciprocity between the soul and the land. The Aymara conceive living beings to have five souls, the most important being the Ajayu. Whilst losing any of the remaining four souls is often related to illness, to lose the Ajayu is to perish. However, the Aymara notion of passing spans beyond our physical death, given that the Ajayu persists through the land and mountains, serving as “Apus” or protectors of the community (Robledo p.3). Nature, in its entirety, is considered to be a living being that possesses an Ajayu, so the means to access their ancestors is always through the land by performing rituals and offerings. Aymara cosmology is based upon the notion that if you’re gentle to the land and your ancestors, they will be gentle to you in return, which is why their foodways are closely tied to their spirituality.

Offerings and sacrifices are constant, cyclical practices that help the Aymara secure a good relationship with their ancestors. In these rituals, food is offered for a good harvest and animals are sacrificed to serve as spiritual guides to those crossing the river towards the mountains (those who have passed away). Moreover, the very structure of Aymara foodways is designed to adapt to the land rather than destroy it. This is reflected through the predominance of concentric circles and “Andenes” (terraces) which span through the landscape, preserving its natural shape and topography (Kessel p.11).

FOODWAYS: TOTORA

The geographical area where the Uros are located, Lake Titicaca, has very specific weather and topographical conditions to which the group had to adapt in order to sustain themselves. This notion of adaptation is central to Aymara/Uro’s identity and is directly built by their relationship to Totora (also known as Chullu), which is what the Uros Islands are made from. During the rainy season, clumps of Chullu roots naturally float with the floodwaters out into the open lake, where the Uros will collect them to start forming floating islands. Bundles of green Chullu are laid horizontally on top of the root clump foundation in overlapping criss-cross layers until they build up four to seven meters. A finished floating island typically has about 1-2 meters of Chullu reed above the water, with an island depth of about 8 meters to support it under the water. Because part of their cosmology relies upon spiritual reciprocity, instead of disrupting the natural landscape, the Uros learnt to coexist with it, which is why Totora became their first food. The Totora root is the only part of the plant that is ingested, which serves as a great source of iodine for the Uros. However, it’s a first food that’s used in its entirety for tons of different purposes such as clothing, mats, baskets, material to build their houses, and burnt as fuel for cooking (Huamanchumo p.13). The picture on the right is of a dish known as the soup of Carachi Amarillo, taken by one of our team members who visited the islands a few years ago and tried this fish-based soup!

One of the most important uses of Totora is as a means of transportation, since it is used to build the “Caballitos” or fishing boats. Fishing is also pivotal to the Uro identity due to the importance and centrality of the lake as their main source of food, which is gifted by their ancestors. The “Caballitos” are the result of a strong communal effort of subsistence, which we will discuss later. We see that the Uros’ relationship with Totora aligns well with the concept of spiritual reciprocity, given that they also recognize the value that the plant has to the land. The animals that support the Uros’ diet, such as fish and birds, all depend on the Totora to sustain themselves in their natural habitat, which is another reason why it is a first food for the community as a whole, including the ancestors.

Below is a recipe for one of the many traditional dishes that the Uros community makes in their households. This particular dish is called Chupe de Quinua, chupe referring to a stew with a variety of vegetables and protein, in this case, quinoa with potatoes, squash, corn, among other delicious vegetables. Our group has made a video on how to prepare this delicious recipe for anyone who is interested! While you’re cooking, enjoy the song “Chuklla” by Uro composer, “Waskar Amaru,” based in Puno.

Watch Now

Chupe de Quinua Recipe: (Serves 4)

Ingredients:

3 cups of boiled Quinua

1 medium red onion, diced

1 tablespoon of crushed garlic

3 tablespoons of “aji colorado” (red chilli pepper)

3 tablespoons of ground “aji amarillo” (yellow chilli pepper)

1 teaspoon of pepper

1 teaspoon of cumin powder

1 handful of oregano

Salt to taste

Oil (necessary amount)

½ cup of diced squash

½ cup of celery

½ cup of chopped leek

1 medium chopped carrot

½ cup peas

½ corn

2 chopped medium-sized potatoes

50 grams of fresh cheese

1 huacatay leaf

1 handful of finely chopped cilantro

1 yellow chilli pepper roasted on fire

Steps:

Add oil to the pot. Once heated, add onion and garlic until garlic gives off an aroma.

Add all the spices and stir.

Add the remaining vegetables and stir. On the side, grill your aji amarillo straight on the stove.

Add water until all vegetables are properly soaked and stir.

Add your boiled quinoa and stir for a few seconds.

Put a lid on for the chupe to boil faster, while adding the grilled aji amarillo.

Stir every once in a while and serve with cilantro on top!

AGRICULTURAL TECHNIQUES

As discussed previously, The Uros people share a lot of cultural practices with the Quechua and Aymara, which is why their agricultural techniques are fairly similar as well. Because of geographic and ecological factors, including high elevation and the dry, cold climate, the Uros did not cultivate their own crops until fairly recently (Dàmaso et al., p. 11). Instead, their main source of survival is through fishing and hunting, where the Uros hunt for native species of fish such as el carachi, el ispi, el mauri, and more commercial species including trout, which are readily available in the bodies of water where they live (Contreras). The Uros also hunt for ducks and grow guinea pigs (cuys), pigs, and chickens on their islands for later consumption (The Uros People of Lake Titicaca). This demonstrates how nearly all of the food grown and activities conducted by the Uros are purely for subsistence. They do not usually engage with the domestic market whatsoever.

Totora reed, being their staple food, is an extremely time-consuming plant to cultivate and take care of. Each reed requires relatively long hours of labor, and perfection is important because the Uros’ islands need to be well-built and weather resilient, through the interweaving of reeds and making sure they are tight enough to be used for shelter or transportation. However, Totora has other applications besides building, such as dried fuel burnt in pottery appliances for cooking (pottery pictured below). It also serves the purpose for pain relief, as a herb for tea, and even as a hangover cure (The Uros People of Lake Titicaca). It can also be manipulated in the building of boats, which is the Uros’ main form of transportation to and from the city of Puno. Since the material wielded for the boat needs to be extremely strong and durable, this Totora is specifically cultivated in pukios, also known as wachaques, balsares or totorales, which are sunken beds found in protected reserves (Banack et al., p. 12).

The Uros men are usually who engage in the boat-building task which can take up to 1 month if approximately 5 men are working on it (Mendez, p. 8). The process involves cutting and drying basal leaves, called moka, along with the totora plant on the sand. Usually, the best selection of these plants are the ones who are 8 months to 1 year old, because they are in the optimal condition in terms of durability and softness to be manipulated into the shape of a boat. Once the selection process is complete, they use instruments like Le ena to shape the plants by hitting on the stems and Carabato, adopted to compress totora stems (Mendez, p. 9). By using these tools, they eventually create the shape of the boat and then start wrapping it with string made of fibers until it is deemed to be strong enough. When it comes to dividing tasks overall, cultivation is considered to be a man’s job, usually applied to the elders, as the younger men build their boats and fish every day. On the other hand, women are responsible for collecting the fish, drying them out, and selling any surplus in the market. In general, while men do the hefty work, women are responsible for managing family finances and doing more of the monetary tasks.

The Uros men are usually who engage in the boat-building task which can take up to 1 month if approximately 5 men are working on it (Mendez, p. 8). The process involves cutting and drying basal leaves, called moka, along with the totora plant on the sand. Usually, the best selection of these plants are the ones who are 8 months to 1 year old, because they are in the optimal condition in terms of durability and softness to be manipulated into the shape of a boat. Once the selection process is complete, they use instruments like Le ena to shape the plants by hitting on the stems and Carabato, adopted to compress totora stems (Mendez, p. 9). By using these tools, they eventually create the shape of the boat and then start wrapping it with string made of fibers until it is deemed to be strong enough. When it comes to dividing tasks overall, cultivation is considered to be a man’s job, usually applied to the elders, as the younger men build their boats and fish every day. On the other hand, women are responsible for collecting the fish, drying them out, and selling any surplus in the market. In general, while men do the hefty work, women are responsible for managing family finances and doing more of the monetary tasks.

The Uros boat-building process requires only one plant for several functions, which has fascinated sociologists and engineers who are in search of sustainable ways to create transportation vehicles without contaminating the environment (Mendez, p. 9). Reed boats are quickly becoming one of the top options due to the fact that they do not require many building tools and that they are an eco-friendly alternative to other types of water transportation. Even though these may seem like positive outcomes for the environment, the Uros fear that this will interrupt the supply of Totora, as the demand for reed boats increases. Industrial companies could get the chance to invade their lands and take away their most important plant.

EFFECTS OF GLOBALIZATION

As governments always do, the federal government found a way to eventually provide tourism access to the floating islands of the Uros, which has impacted these communities in several ways (Cheong, p. 42-43). As the tourism industry has grown, the Uros have been able to both create agency for themselves and exert control over this increased yet sustainable tourism. They have been able to do this through partnerships with the regional and federal governments of Peru ensuring that their daily lives are not impacted in a negative way by bringing in tourists. The Uros saw tourism as an opportunity for economic growth so that parents could invest in their children’s education and improve their overall standards of living. However, some locals believe that tourism and globalization have threatened their culture and identity, where ideas of sustainability are being taken away from these Indigenous groups and given a more industrial perspective, attracting investors who want to take away their land and resources.

Even though the Uros have been able to receive more autonomy over the tourism industry, the government has still made some decisions that have impacted the way the Uros use their land. Since the government declared some of the lands as public, near where the Uros reside, they can no longer extract the Totora plants growing in those areas and use them for their beds, which is essential considering the supply of Totora is decreasing (Banack et al., p. 16). Furthermore, the media has had a significant impact in letting others see what the Uros communities have to offer, meaning an influx of tourism and guides using motorboats that affect the fish and wildlife population in the region, cutting down on the amount of food available for locals (Cheong, p. 76). Moreover, thanks to the close geographical proximity of the city of Puno, where urbanization has taken place for the past few years, contaminated waters have caused areas near the Uros houses to be prone to eutrophication, which is characterized by excessive growth of algae leading to oxygen depletion in the water. This drastically affected the fishing industry, in reaction to which the Uros had to collaborate with authorities to create policies for water contamination that ensure minimal environmental degradation and protect the food supply of the local community (France and Syarifuddin, p. 291). Issues like these have proven that it is necessary for the Uros to form partnerships in order to increase their income through tourism and secure access to the market, but also to preserve their culture and traditions.

A rise in interconnectedness to the city of Puno has allowed the Uros to obtain easier access to materials that have helped them in the construction of boats and houses. For example, since they know the totora plant is getting harder to cultivate and use in their everyday lives, the Uros use plastic bottles or other objects for their boats, as it provides the same purpose as the totora plant in boat-building (Banack et al., p. 15). Not only does this let them conserve their staple food, but it also appeals to tourists, as outsiders see recycling plastic material as an alternative and sustainable solution. Caballitos are also being built in bigger sizes with more intricate faces since, as we have discussed in previous classes, foreigners feel more attracted to objects that look more complex, exotic, different. Thus, like the Maya, the Uros have turned to strategic essentialism as a means of participating in the tourist market. Another advantage that the Uros have gained thanks to the rise of the tourism industry in their area has been channelled through which they can not only learn, but can also showcase their food and culture, such as through local restaurants. Restaurante Flotante “Suma Kurmi,” created by Gina Lujano Suaña, a 24-year-old woman from the Uros community, has become a national sensation for any tourist who wants to visit the Uros Islands (Contreras). The restaurant’s name, meaning “beautiful rainbow” in Aymara, represents a source of income for her family as well as a pathway for tourists to try some of the traditional dishes of the Uros. In an interview with Gina, she mentioned that instead of using the native fish species such as el acarchi, el ispi, or el mauri, she uses trout, a more commercial fish that they are comfortable cooking and tourists are comfortable trying. At the culinary school Gina attended, she noticed that these schools seem to focus more on the preparation and service rather than the origins of the meal, and wished that they taught more about where their ingredients come from and how they can respectfully prepare them without depleting them, one of the main reasons why she built her restaurant to implement this vision. This is yet another clear example of how the Uros are using different forms of media to get their message across and ask tourists to be more mindful of their spaces and food in such a rapidly changing environment.  Now, specifically referring to the changes that technology has provided to the Uros people of Peru and Bolivia, we can see these have had mainly positive outcomes. The Peruvian government has been able to arrange, through an independent contractor, solar panels on all of the islands so that there is access to satellite TV as well as solar energy to be used for electricity (Dupre). The communities have to pay a monthly fee for up to seven years to repay the government for these installations, as a means of forcing them to participate in the monetary market. The Uros, however, generally do not see it in this way. They have been introduced to a more modern way of living, and they are now able to connect to city dwellers and urban services they did not previously have (Mendez, p. 6). Thanks to the increased connection between Puno and the Uros, the younger population of the Uros frequently prefer living in the city or visiting more often thanks to the increased employment opportunities to sustain their families. The older population often travels to Puno as well, or to less remote areas where tourists visit

Now, specifically referring to the changes that technology has provided to the Uros people of Peru and Bolivia, we can see these have had mainly positive outcomes. The Peruvian government has been able to arrange, through an independent contractor, solar panels on all of the islands so that there is access to satellite TV as well as solar energy to be used for electricity (Dupre). The communities have to pay a monthly fee for up to seven years to repay the government for these installations, as a means of forcing them to participate in the monetary market. The Uros, however, generally do not see it in this way. They have been introduced to a more modern way of living, and they are now able to connect to city dwellers and urban services they did not previously have (Mendez, p. 6). Thanks to the increased connection between Puno and the Uros, the younger population of the Uros frequently prefer living in the city or visiting more often thanks to the increased employment opportunities to sustain their families. The older population often travels to Puno as well, or to less remote areas where tourists visit  in order to sell their handicrafts, especially since their islands are unable to sustain the number of tourists that try to visit. However, because of the frequent use of boats to transport people to and from the city, the water has been polluted to the point where locals can no longer use it as a source of fresh water for consumption (Totora-Ark of Taste). What used to be an easy task of getting a bucket and swinging it into the lake for drinking, cooking, and cultivating, has now turned into travelling long distances to be able to consume fresh water. Operation Blessing, an organization responsible for alleviating human suffering all over the world, has heard about these issues and decided to implement the Kohler Clarity filter on the islands for fresh and clean consumption of water without having to travel very far (Burbach). This is another example of how globalization and its effects are mutually constituted with the resulting remedies. Globalization and water pollution are co-constitutive with non-profit intervention and water purification systems.

in order to sell their handicrafts, especially since their islands are unable to sustain the number of tourists that try to visit. However, because of the frequent use of boats to transport people to and from the city, the water has been polluted to the point where locals can no longer use it as a source of fresh water for consumption (Totora-Ark of Taste). What used to be an easy task of getting a bucket and swinging it into the lake for drinking, cooking, and cultivating, has now turned into travelling long distances to be able to consume fresh water. Operation Blessing, an organization responsible for alleviating human suffering all over the world, has heard about these issues and decided to implement the Kohler Clarity filter on the islands for fresh and clean consumption of water without having to travel very far (Burbach). This is another example of how globalization and its effects are mutually constituted with the resulting remedies. Globalization and water pollution are co-constitutive with non-profit intervention and water purification systems.

These are some of the many ways the Uros have participated and been affected by a rapidly globalizing world. Even though there have been significant impacts on the sources and homes of the Uros, locals continue to survive and find solutions to coexist.

Bibliography

Albó C., X. “Aymaras Entre Bolivia, Perú Y Chile”. Estudios Atacameños, vol. 19, no. 1, pp. 43-74, doi:10.22199/S07181043.2000.0019.00003.

Banack, Sandra Anne, et al. “Indigenous Cultivation and Conservation of Totora (Schoenoplectus Californicus, Cyperaceae) in Peru.” Economic Botany, vol. 58, no. 1, 2004, pp. 11–20. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/4256771.

Browman, David L. “Titicaca Basin Archaeolinguistics: Uru, Pukina and Aymara AD 750–1450.” World Archaeology, vol. 26, no. 2, 15 July 2010, pp. 235–251., doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00438243.1994.9980274.

Burbach, David. “Uros – Water Everywhere, But None to Drink.” Operation Blessing, 7 Aug. 2017, www.ob.org/uros-water-everywhere-none-drink/.

Cheong, Caroline S. “Sustainable Tourism and Indigenous Communities: The Case of Amantaní and Taquile Islands.” Thesis / Dissertation ETD, University of Pennsylvania, 2008, pp. 1–119.

Dámaso, Nilton Vela, y Niltonveladamaso. “‘Qhas Qot Zuñinaka’ Las Personas De Agua y Lago.” Issuu, Ministerio De Cultura – Perú, 2019, issuu.com/niltonveladamaso/docs/libro-catalogo_qhatqotzu_inaka.

Dupre, Brandon. “How This Peruvian Village Is Building Homes on a Floating Island.” Culture Trip, The Culture Trip, 21 Dec. 2017, theculturetrip.com/south-america/peru/articles/the-process-of-building-huts-on-the-uros-island-peru/.

Esper, Federico. Tourism and Culture Partnership in Peru. World Tourism Organization, 2016.

Kessel, Juan Van. Tecnología Aymara: Un Enfoque Cultural. CIDSA, 1993.

Mendez, Rocio Torres. “Uros Hand Made Reed Floating Islands.” Fraunhofer, Rotterdam (Netherlands) in-House Publishing, 2010, www.irbnet.de/daten/iconda/CIB21650.pdf.

Mendiola Vargas, Cecilia. “Totora – Arca Del Gusto.” Slow Food Foundation, 9 Dec. 2018, www.fondazioneslowfood.com/en/ark-of-taste-slow-food/totora-2/.

Contreras, Catherine. “Suma Kurmi: La Historia De Un Restaurante Que Flota Sobre El Lago Titicaca.” Redacción El Comercio Perú, NOTICIAS EL COMERCIO PERÚ, 18 July 2017, elcomercio.pe/gastronomia/peruana/uros-gastronomica-restaurante-flotante-isla-totora-443182-noticia/?ref=ecr.

Robledo, Richar Parra. “Muerte, Purificación y Vida.” Aries, 16 Nov. 2019, aries.aibr.org/articulo/2019/20/1779/muerte-purificacion-y-vida-el-alma-en-la-cosmovision-aymara.

Sandoval, José Raul, et al. “The Genetic History of Indigenous Populations of the Peruvian and Bolivian Altiplano: The Legacy of the Uros.” PLoS ONE, vol. 8, no. 9, 2013, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0073006.

Syariffudin, Evi. “Living over Water: Introduction to Ecotourism Development Concerns for the Tonle Sap, Cambodia, and Lake Titicaca, Peru.” Restorative Redevelopment of Devastated Ecocultural Landscapes, by Robert L. France, CRC Press, 2016, pp. 227–293.

“The Uros People of Lake Titicaca.” Peru Hop, 30 Jan. 2020, www.peruhop.com/the-uros-people-of-lake-titicaca/.

All photographs used in this blog are courtesy of Sophia-Joe Lunny.

Lecture By: Valentina Gonzalez, Grace Livengood, Khushi Malhotra, and Sophia-Joe Lunny