Group 13 members with all smiles at the poster session.

Coming back from the Reading Break at the end of February, our group launched into our interview phase; the hands-on community engagement piece many of us had been longing to start. What we were not prepared for, however; was the month-long debacle of tracking down business owners and securing interview times. While we had collaboratively written a template email to send out to businesses, we found positive responses few and far in between. Despite persisting with follow-up emails and cold calls, by the 2nd week of the month we had only managed to secure half our intended number of interviews. With mild panic settling in with the lack of responses from the businesses we had contacted, we reached out to our community partner for help.

Throughout this process, Kevin was able to connect us to businesses through his personal connections. Interviews seemed to magically fall into our lap after Kevin reached into his network. With his aid, we were able to get three additional interviews to the ones we managed to secure. While our personal efforts felt like pulling teeth, we were amazed by the time and energy Kevin’s contacts were willing to take to participate in our research project.

Our experiences engaging with community members in Chinatown revealed the importance of a liaison in asset-based community development. Not only was Kevin able to secure interviews for us, but his personal connections with our interviewees made for enriching conversations that provided key information. We found his presence, as well as Christina’s, reassuring and instructive. It was fascinating to watch how easily Kevin’s personal contacts would open up, sharing key information that our individual group members would have much more difficulty capturing on our own.

The title of our “Flexible Learning” days resonated more and more as we realized the importance of embodying flexible learning. While we had created a tidy timeline for how we imagined our project would unfold, few if any of the deadlines we had previously set were met in reality. We found ourselves feeling uncomfortable with the uncertain future as the days went by with what seemed to be little to no progress. The lack of security about the future of our project was challenging to deal with, but somewhere along the way, it became inherent that embracing this factor was the pathway to our success.

Becoming “flexible learners” for us meant being nervous during our first interviews, but improving from our mistakes. It meant going out of our way to reschedule our activities for a last minute interview. It meant going off-script during the interviews to ask bold questions. It meant challenging our ideas of what was the “right” or “proper” way to do things and finding alternatives. As Shulman highlights: “without a certain amount of anxiety and risk, there’s a limit to how much learning occurs” (2005, p. 18). This became apparent as we embarked on our interviews since most of us held little to no experience conducting interviews prior to this project. As we observed Kevin and Christina’s ways of engaging with interviewees, we found ourselves learning important interview skills and applying them when we had the chance. While we had moments of anxiety and regret, (i.e. not having the boldness to probe deeper with certain interviewees), we were able to take our experience in stride and improve upon in consequent opportunities. We found that our collective confidence grew through the interview process.

The interviews were also an excellent opportunity to apply the concept of “asset-based community learning” which has been an ongoing theme throughout our course and project. Community projects, while well-intentioned can veer towards a “needs-based approach” where outside experts “play up the severity of problems” and “[present] a one-sided negative view” in order to extract results that are needed for the purpose of the study (Mathie & Cunningham, 2003, p. 476). Going into the interviews, we kept this in mind and maintained an open-minded approach, remembering that our role as outsiders was to listen and learn from the members of the community – the true experts in this scenario. Ultimately, this approach paid off well as we not only learned about inter-business relations which was the focus of our interviews, but we also gained invaluable insight into the personal growth stories of each business, and the ideals each business owner had for their community. This not only made the interviews more interesting but also gave us more insight into opportunities that utilize the community’s assets and benefit its members as a whole; something to consider as we make suggestions in our final report.

Infographic of our study’s findings.

Lastly, our experiences have allowed us to reflect on our own learning. Shulman (2005) asks, “are there signature pedagogies in undergraduate liberal education?”. (Signature pedagogies being distinctive teaching practices) He argues that lecture-style courses often foster environments where students are “disengaged, invisible, unaccountable, and emotionally disconnected”. However, we were able to see how the LFS 350 course and community projects reflect features of certain “signature pedagogies”. For example, Shulman (2005) notes that a universal feature of signature pedagogies is that they make students feel deeply engaged, highly visible and potentially even vulnerable. According to the article, learning requires that students feel visible and accountable – signature pedagogies tend to be interactive, so students feel accountable to instructors, as well as to fellow students. Shulman’s observations resonated with our group – we felt that the LFS 350 learning environment exemplified these aspects of the signature pedagogies through the smaller tutorial discussions, group work, and interactions with our community partners.

In our collaboration with the hua foundation, we felt connected and engaged with the work we were doing because it was a real-life application of the topics we have been learning in class. Working with the organization and conducting interviews also put us out of our comfort zones (as Shulman noted, making us feel “vulnerable”) and challenged us to develop new skills. This course made us feel visible in comparison to a typical lecture-style course – we felt more deeply involved in the course and the learning materials because of the class structure and community partner project.

In preparing for the final report, we know that there will likely be roadblocks along the way. The questions our research project asks do not have simple answers and will require wrestling with complex ideas and concepts. Especially as the end of the term increases in workload for all of us, we will need to continue to be “flexible learners” and embrace the uncertainty of what this project entails.

We will be able to take the skills we gained throughout the interview process and apply them to future interviews and similar situations. While Kevin and Christina’s expertise helped us probe deeper during our research phase, it also introduced a certain amount of bias to the answers through leading questions, which will be acknowledged in our final report. Additionally, of the seven interviews we conducted, many had prior connections to the hua foundation or a personal connection to Kevin. As a result, the data collected may not be representative of all new Chinatown businesses and may be biased towards values of the hua foundation.

As highlighted in the “Writing Up Science-Based Practical Reports” (Harper Adams University, n.d.) guide, we must write objectively, removing bias, emotions and subjective writing. In future interviews, we will not have the luxury of having someone with a wealth of knowledge present. However, this highlights the need for having an in-depth understanding of the local history and context of wherever our projects may take place. Furthermore, the essence of asset-based community development involves the mobilization of community members and their assets (Mathie & Cunningham, 2003), and it will be our duty to empower community members and aid them in building on their current strengths. It will be a lengthy and potentially unsmooth process, as cooperation requires mutual trust, and trust requires time, commitment and mutual understanding. Hopefully, in future situations, we will have more time to gain this understanding by connecting with local stakeholders and community members.

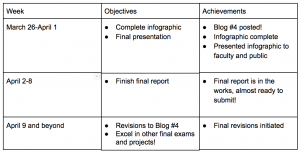

Where we were this week and where we will go next week

References:

Harper Adams University. (n.d.). Guide to Essay Writing 2017/18. Retrieved March 30, 2018, from https://cdn.harper-adams.ac.uk/document/page/127_Guide-to-Essay-Writing.pdf

Mathie, A., & Cunningham, G. (2003). From clients to citizens: Asset-based Community Development as a strategy for community-driven development. Development in Practice, 13(5), 474–486

Shulman, L. S. (2005). Pedagogies of uncertainty. Liberal Education, 91(2), 18–25. Retrieved from http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ697350.pdf