President of Rwanda on Aid.

http://www.azquotes.com/quote/152046

I will begin by quoting Dambisa Moyo in her book Dead Aid, “No country has ever achieved economic success by depending on aid to the degree that many African countries do” Aid has been seen and painted as the force that will drive most African countries out of poverty and allow them to “catch up” with its counterparts in the west in terms of development and economic growth. References are constantly made to the Post World War 2 Marshall plan in Europe that was apparently very successful. Americans donated up to $13 Billion to the war- torn economies of Europe in an attempt to revive these economies. Critics however say that European countries economies would have emerged from that mess with or without the US Marshall Plan. It is argued that if aid worked for Europe then it is no doubt bound to work for African countries as well, as long as good government policies and structures are put in place (Bovard 1986). This sounds really good in paper but I can’t comprehend why after decades of foreign aid in billions of dollars being pumped into Africa, the poor in Africa still languish in poverty and the numbers are anything but diminishing. I therefore argue that foreign aid does not work and it is high time that the key stakeholders in the ever-growing aid industry alias international development went back to the drawing board.

This cartoon perfectly captures the situation on poverty and aid.

www.polyp.org.uk

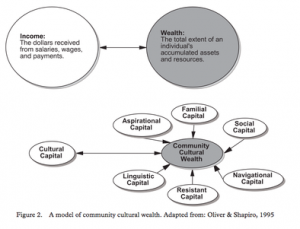

Poverty alleviation initiatives now approach poverty as a multi-dimensional deprivation of entitlements, capabilities and rights and not merely of income (Green 2006). Maia Green, in ‘Representing Poverty and Attacking Representations’, however argues that this revised definition was inspired more by institutions subscription to the Millennium Development Goals than by the ability to capture the experiences of the poor. It is therefore ironic that we hope to eliminate poverty among the world’s poor yet we exclude the very people that we hope to serve from key decision making processes. Most international organizations go into these communities with the notion that they know better and are more knowledgeable in matters international development only to be faced with a complexity and uniqueness of challenges. These not only make it impossible for such projects to be sustainable but they also undermine the entrepreneurial efforts by citizens in those countries as was alluded to in the film Poverty Inc.

Corruption is still rampant in most African countries and Aid seems to be propagating this as opposed to helping governments curb corruption. The African union estimates that corruption costs the African continent $150 billion a year. Giving money to countries whose internal structures are failing without holding them accountable does more harm than good. Aid money goes into the pockets of the elite few who are called governments at the expense of vital services like health, education, infrastructure that benefit the poor. As Andrew Mwenda alludes to in his TED TALK. External factors can only present an opportunity but the ability to use those opportunities and turn them into advantages relies heavily on internal capacity. We therefore need to focus more on building the internal capacities of countries in need of assistance before we can resort to aid which only worsens existing conditions for the poor.

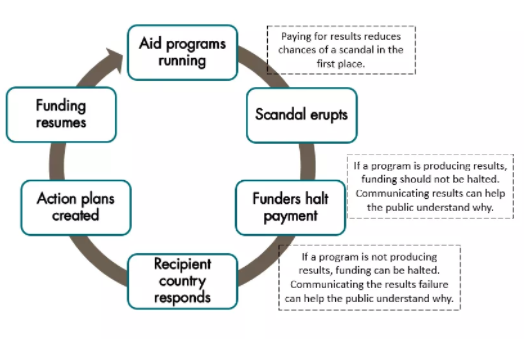

Possible solutions to help minimize corruption that is all too common in Aid. https://globalanticorruptionblog.com/2016/06/22/corruption-in-health-aid-escaping-the-scandal-cycle/

Despite major corruption accusations against government officials in countries that are key recipients of foreign Aid such as Malawi`s former president who was charged with embezzling upto $12 million of Aid money, the source of the money never stops sending more (Moyo 2006). This goes against the very ideals that Aid alleges to be based on, to help alleviate poverty and steer economic growth not benefit the select few corrupt government officials enriching them the more. In her book Dead Aid, Dambisa mentions, and I quote, “A constant stream of “free” money is a perfect way to keep an inefficient or simply bad government in power…” she further mentions that as more aid streams in to developing countries, the government is left with little to do other than pay the army and cater to its foreign donors needs in order in stay in power. These governments do not feel the need to raise money through taxes to cater for its citizens.

Povery Inc. is a documentary that perfectly captures the negative impacts of AID in developing countries. Impact to the local economies in these countries are far much greater that most can imagine, unfortunately that is the side of the story that the media never shows/tells. We never hear stories on enterprising and innovative Africans who are working hard to change their stories and that of their communities.

Image from Irish Aid Website showing a group of women carrying water.

https://www.irishaid.ie/what-we-do/who-we-work-with/civil-society/civil-society-overview/

As Kalpana Wilson clearly articulates in Race, Gender and Neoliberalism, the gendered nature of the way the media portrays aid must change. We are only told stories of women in the global south who work hard under extremely difficult circumstances to support their families. Such stories are apparently intended to challenge the representations of passive victims and portray images of hardworking women who are taking control of their lives. Such images, motivated more by the need to raise more funds than to tell the stories of the developing world women seem to have been very successful at masking oppression and exploitation and to even portray such acts as the norm in these countries. She critically analyses the branding skills used by big organizations like Nike in their branding strategies aimed to raise funds to support girls’ education in developing countries. In the video “I dare you” as part of the Girl Effect Campaign. (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-Vq2mfF8puE) she mentions how on one hand the girls are portrayed as individuals who have the potential and will to change their situations and that of their communities if given an education. On the other hand, the creators of the video are communicating that that will only happen if the viewers recognize that potential and give it shape and direction(Wilson 2011). This goes back to the old age narrative of white saviours and is based on the very ideals that colonialism was based on. Organizations thus need to be careful about the messages that they could be passing on to the public either intentional or unintentional. This messages play a key role in shaping perceptions of the global south.

Using Haiti as an example, simple acts of kindness from the international community following a natural disaster quickly turned into an economic crisis for some and an opportunity for others with the biggest losers being the poor in Haiti. It is well called for for the international community to respond when a country is hit by a natural disaster. However, when Aid causes more harm than good then we need to reevaluate our goals. Haiti has received upto $6 billion in foreign aid over the past decade, however it remains one of the poorest countries in the world(Ramachandran et.al 2012). Aid organizations have blamed the Haitian government for this lack of growth yet they seem to forget that the very aid that they give does, to a large extent, propagate these acts of corruption and limit the government’s accountability to its citizens. As the economist Terry Buss says, the large amounts of aid received by Haiti alleviates pressure on the government to provide services that are already provided by aid institutions. In addition, as was noted in the film poverty Inc, Aid creates unpredictable impacts on local economies as was the case in Haiti.

Breaking the cycle of aid dependency involves stopping aid. http://www.slideshare.net/geoffriley/aid-and-development

Young and innovative Haitians joined hands to develop a company that manufactures solar to help solve the power problem that they experienced following the earth quake. However, when aid agencies came in with their so-called compassion, they got companies in the west to donate thousands of Solar panels to Haiti. The young Haitians were of course run out of business because as they put it, “you cannot compete with free”. Despite these organizations being aware of the existence of a local solar manufacturing company, they chose to turn a blind eye. They in turn undermine entrepreneurial efforts by Haitians and propagate the cycle of dependency.

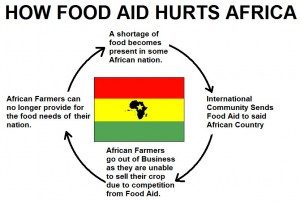

Food Aid is another type of aid that has received both criticism and praise in equal measure. Following the 1984 famine in Ethiopia, it became the largest recipient of food aid is Africa. Up to 2003, Ethiopia had been receiving up to $250 million a year of food aid with most of it coming from the USAID. As food aid kept streaming in, Ethiopian farmers were unable to sell their surpluses from the previous year. They had tonnes of food locked up in warehouses with no market because they simply could not compete with free. Their petitions to the government to ask America to donate money to buy local food bore no fruits.

Why Food Aid is harmful http://www.jonathanlea.net/2015/why-foreign-aid-is-harmful/

In 1943, the US congress passed a bill that American food aid must be grown in America. The US decided to focus on what was best for its farmers and not the world`s hungry. As Thurow et al (2009) the authors of ‘who is aiding whom?’ put it, “Even as American generosity grew— half of all international food aid is provided by the United States— so did its self-interest”. One of the farmers in the book is heard saying that American farmers need Ethiopian famine, otherwise where would all the surplus grown in the US go? When food prices dropped in the US due to over production, the volume of food aid rose. America`s generosity came with conditions which mostly put their interests first. Never mind that it would cost so much less to buy local food in or close to the areas experiencing famine. It was estimated that about 50% of all the costs associated with food aid come from transportation and storage of food. It seems to me that that was the least of US problems. As long as the system was working for them they cared less about farmers in Ethiopia. This creates a cycle of dependency and significantly undermines agribusiness in recipient countries. Food aid is critical when there are deficits in a country and the US generosity has no doubt helped save lives. However, the US needs to revise its stand on food aid so that it cannot further propagate hunger and dependency.

Chimamanda in her famous TED Talk ‘The danger of a single story’ mentions a couple things that stood out to me. She warns of the danger of telling a single story of a people definitively because that is all they become in the eyes of many. The media constantly portrays Africa as a place of despair, a people waiting to be saved by a ‘kind, white foreigner’. This is a narrative that is believed by so many people in the west. The media uses stories to break and malign, but as Chimamanda clearly articulates, stories can also be used to empower and humanize. The reading on ‘Development Made Sexy (2008)’ by Cameron and Haanstra clearly describes the role that the development agencies and media play in shaping representations of development in the global south and the global north. In an effort to raise more funds intended for international development projects, the representations of development have switched from that of scarcity and guilt to the celebration of abundance in the global north.

Madonna in an orphanage in Malawi with her adopted son. http://www.thehindu.com/opinion/op-ed/where-family-aid-offers-alternative-to-orphanages/article61097.ece

The perceived sex appeal and influence of celebrities is now the most wildly used form of representation. By getting celebrities to endorse development causes therefore influencing the opinions and actions of many on matters development, more funds are raised. Cameron and Haanstra however warn that depicting development as sexy may undermine the goal of promoting a deeper understanding of development issues in the global north. They raise 5 critical questions which include whether some issues/forms of agency cannot be represented as sexy and will therefore be marginalized. She also questions whether the shift of focus from the southern others to the northern selves will influence the imagined relations between the north and the south, whether this representation will promote/ mask the underlying structural causes that produce and sustain poverty and social injustices and how it constructs gender identities and relations. These are critical questions that show that representation of development as sexy may not be the better alternative and might infact just be another fund-raising strategy by the development industry whose funds do little to end poverty.

To summarize, I have demonstrated above why AID might not be the be best solution to end world poverty because so far not much progress has been made. I do however recognize that Aid is sometimes necessary to alleviate certain circumstances e.g. natural disasters and war but as mentioned in the film poverty Inc., this should not be a long-term solution. Focus should be shifted to capacity building nations that need support so they can be able to meet their needs in a sustainable manner without relying on external help. What developing countries need is profitable trade partnerships, well paying jobs, both domestic and foreign investments, research institutions, you name it! These are the things that will steer economic growth and development, not aid.

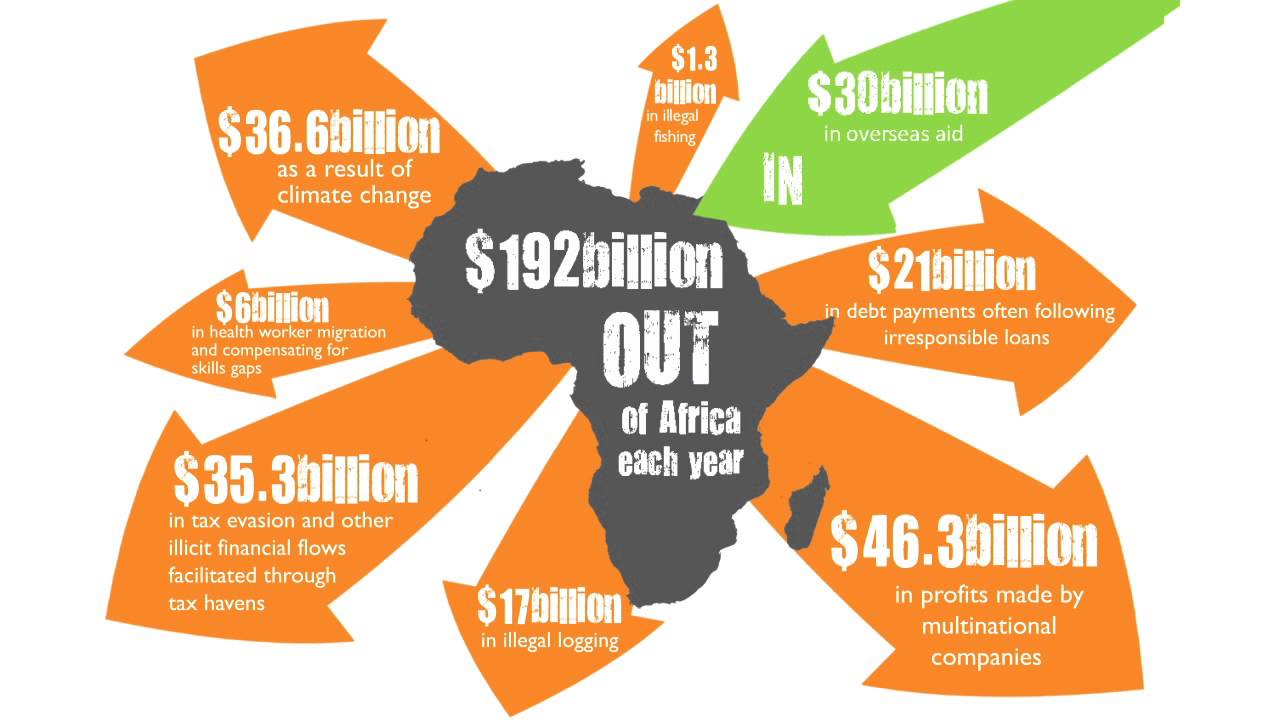

Africa’s billion dollars https://www.youtube.com/user/HealthPovertyAction

As an African, I am excited for the future of African countries, the fastest growing economies are in Africa. With a people so determined to change their stories and how Africa is perceived world over, Africa may just be the next frontier! This also means that development institutions clearly need to revise their ways of doing development work. It is important that the poor become the main focus of development work and not have few individuals benefit from it and maintain the status quo in a system that is simply not working. Media does play a key role in shaping perceptions and they should work hand in hand with development institutions and most importantly the poor in the global south to ensure that they are represented in the most accurate and respectful way possible.

References

- Andrew Mwendwa(2007) TED TALK: Aid for Africa? No Thanks.

- Bovard, J.,(1986). The Continuing Failure of Foreign Aid. Cato Institute Policy Analysis No 65.

- Cameron,J., Haanstra, A., (2008) Development Made Sexy: how it happened and what it means, Third World Quarterly, 29:8, 1475-1489, DOI:10.1080/01436590802528564

- Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie(2009) TED TALK: The Danger of a Single Story.

- Green, M., (2006) Representing poverty and attacking representations: Perspectives on poverty from social anthropology, The Journal of Development Studies, 42:7, 1108-1129, DOI: 10.1080/00220380600884068

- Moyo, D. (2009). Dead aid: Why aid is not working and how there is a better way for africa(1st American ed.). New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- Poverty Incorporated: Fighting Poverty is Big Business, But Who Profits the Most? By Michael Matheson Miller

- Ramachandran, V., & Walz, J. (2015). haiti: Where has all the money gone?Journal of Haitian Studies, 21(1), 26-65.

- Thurow, Roger; Kilman, Scott. (2009): Enough: Why the World¹s Poorest Starve in and Age of Plenty. Journal of PublicAffairs. Ch 6: Who’s Aiding Whom?

- Wilson,K., (2011) ‘Race’, Gender and Neoliberalism: changing visual representations in development, Third World Quarterly, 32:2, 315-331, DOI: 10.1080/01436597.2011.560471