“Like traditional landscapes, video game landscapes incorporate the moral ideologies of their producers and therefore limit or direct the kinds of lessons about the real world that players might learn. Video game landscapes may therefore reinforce the dominant ideologies that govern the production of real world landscapes as much as they challenge them”

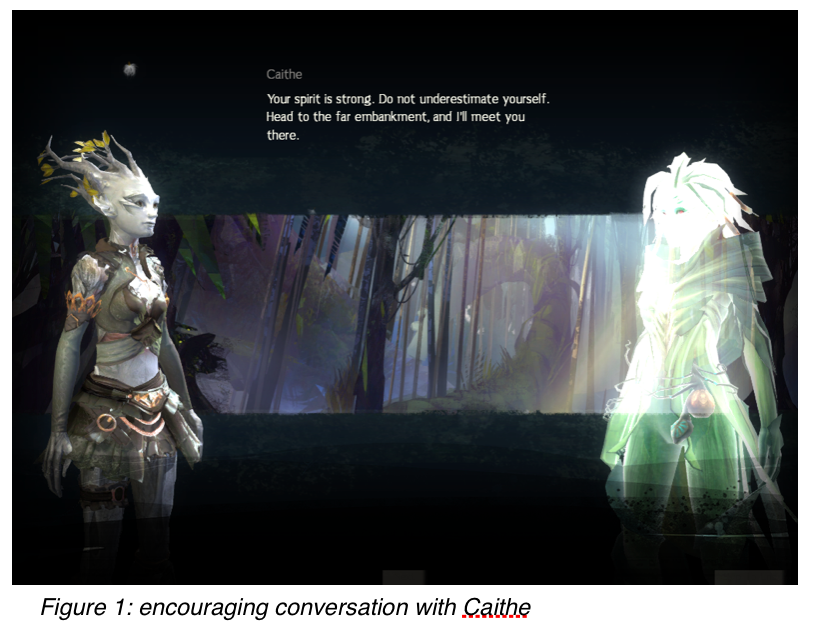

As I entered the game for the first time, I was greeted by a mysterious character called Caithe. Through a series of conversation with Caithe (Figure 1), Caithe had emphasized that my spirit is strong and to never underestimate myself. Followed by this pep talk, I was then released to the actual game field called the Caledon Forest.

The Caledon Forest is as magical as it sounds. The entire landscape is nature-filled, with bright earthly colours and magical creatures. I was encouraged to explore the different sceneries of the game field. However, not long after I get to enjoy myself in this magical world, I was soon informed that the village is being invaded by the “termite larvae”. In effort for the peaceful inhabitant to live in the utopian world, I have to kill the termites and protect the inhabitants from these evil creatures.

Once the quest started, the entire colour scheme changed. The background music also shifted into a darker tone, signifying that a catastrophic force is emerging. The landscape became gloomy and dark (Figure 2). The surroundings were filled with the invaders. The shifts provide a sense of urgency and destruction. In fact, it effectively calls for action, informing the players that fighting against the evil creatures is deemed necessary to help the Forest and its inhabitants to regain peace.

It wasn’t hard to target these creatures because they were labelled with a red tagline of “termite.” In comparison, other avatars and characters were labelled with a green tagline of their names. These colour codes made it easier to make a distinction between who the protagonists and antagonists are.

Upon completing the task as instructed, it became evident that the pleasures players gain from the game stem from the tension of the good and the bad. The game polarized the two ends. Just as the pep talk was given by Caithe, we were informed that we have the spirit and strength as the protagonists of the game, in which the good force made us invincible and indestructible. We were given power because we have to fight against the evil deeds such as the termites.

However, as Logan suggested that “ video game landscapes may, therefore, reinforce the dominant ideologies that govern the production of real-world landscapes as much as they challenge them,” Guild War 2 as well as the production of these dominant ideologies. The ideologies of “destroying the evil” were also predetermined upon entering the game. We were taught who the invaders are. With no prior knowledge of the species historical background, we were seduced by the idea that the antagonists are destined to be destroyed. As players, we became invested in this storyline – that to protect our loved ones ( such as to restore the utopian Caledon Forest), we, as the protagonists, have to gain more power to fight back the odds that are against us. However, the idea that we can take control of our surrounding is illusional. Just as the dominant ideologies reinforced by the contemporary real world, the idea of who should be granted with social acceptance and who should be alienated are often governed by those who have power. They continue to reproduce the ideologies of social status and hierarchy because such social structures act in their best interests.

References:

Michael W Longan. “Playing with landscape: social process and spatial form in video games” Aether Vol. 2 (2008)