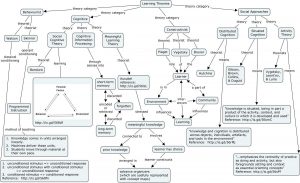

To design a framework incorporating all the theories, one needs to understand each theory in depth, its philosophy, focus, its primary audience. Only then can one connect the dots and visualize a coherent picture weaving together the different learning theories. Following is a brief description of the various learning theories currently in practice. Please click on the ‘read more’ button for reading in details.

Behaviourism: Endorsed by B.F. Skinner, John Watson (1878–1958), van Pavlov (1849–1936), Edward Thorndike (1874–1949) among others, explained human and animal behavior regarding external physical stimuli, responses, learning histories, and (for certain types of behavior) reinforcements. It claims that people have no free will – a person’s environment determines their behavior. We learn new behavior through conditioning. Thus learners are passive and can be trained to display favorable behaviors through reinforcements, practice, and external motivation. The learner is expected to progress in a linear quantitative fashion where the progress made by the learner is measured by observing behaviors on predetermined tasks (Fosnot, 2013).

Cognitivism: In the late 1950s, learning theory began to make a shift away from the use of behavioral learning models to understanding more complex cognitive processes such as thinking, problem-solving, language, concept formation and information processing (Snelbecker, 1983). Cognitive theories focus on the conceptualization of students’ learning processes and address the issues of how information is received, organized, stored, and retrieved by the mind. Learning is concerned not so much with what learners ‘do’ but with what they know and how they come to acquire it (Jonassen, 1991). Cognitivism, like behaviorism, emphasizes the role that environmental conditions play in facilitating learning. Instructional explanations, demonstrations, illustrative examples and matched non-examples are all considered to be instrumental in guiding student learning. Additional key elements include the way that learners attend to, code, transform, rehearse, store and retrieve information. Students’ thoughts, beliefs, attitudes, and values are also considered to be influential in the learning process (Winne, 1985).

Maturationism: Actively endorsed by Arnold Gessel(1931), maturationism is an early childhood educational philosophy that sees the child as a growing organism and believes that the role of education is to support this growth passively rather than actively fill the child with information. This theory maintains that children mature as they grow older. Personalities and temperament will be revealed with little influence from the surrounding environment. From a maturationist’s perspective, children’s environments should be adapted to their already genetically determined needs and characteristics.

Constructivism: Constructivism is endorsed actively by Piaget, Vygotsky, Bruner, Von Glasersfeld. According to both behavioral and cognitive theories, the world is real, external to the learner. The goal of instruction is to map the structure of the world onto the student (Jonassen, 1991). However, constructivism is a theory that equates learning with creating meaning from experience. Constructivists do not deny the existence of the real world but contend that what we know of the world stems from our interpretations of our experiences. Humans create meaning as opposed to acquiring it. Both learner and environmental factors are critical to the constructivist, as it is the specific interaction between these two variables that creates knowledge. Piaget proposed a theory of assimilation and accommodation where, when the learner’s existing mental models are disturbed by new experiences or information, then learner tries to accommodate the new understanding in the existing schema, thereby leading to learning. Social constructivism is a variant of constructivism which focuses on social interaction as a cause of meaning making. For constructivists, learning is not the result of development; learning is development (Fosnot, 2013).

Constructionism: Developed by Seymour Papert, in his words, “Constructionism shares constructivism’s view of learning as “building knowledge structures” through the progressive internalization of actions. It then adds the idea that this happens especially felicitously in a context where the learner is consciously engaged in constructing a public entity, whether it’s a sand castle on the beach or a theory of the universe” (Ackermann, 2016). Papert claims that “diving into” situations rather than looking at them from a distance and the connectedness rather than separation, are powerful means of gaining understanding. Becoming one with the phenomenon under study is, in his view, a key to learning. Thus, situated and problem-based learning is an important part of constructionism. Papert’s constructionism focuses more on the art of learning, or ‘learning to learn’, and on the significance of making things in learning.

Connectivism: Proposed by Siemens and Downes, connectivism is a theory for 21st-century learning. Siemens claims that learning is no longer an individualistic activity. Knowledge is distributed across networks. In our digital society, the connections and connectedness within networks leads to learning. Siemens argues that a central tenet of most learning theories is that learning occurs inside a person. However, these theories do not address learning that occurs outside of people (i.e. learning that is stored and manipulated by technology). He specifically questions how does learning theory change when information storage, processing, and recall are off-loaded onto devices and through networked connections? In the brain, knowledge is distributed through connections between different regions of the brain and in the networks we form (social and technological) knowledge is distributed through connections between individuals, groups, and devices (Siemens, 2006).

Connectivism: Proposed by Siemens and Downes, connectivism is a theory for 21st-century learning. Siemens claims that learning is no longer an individualistic activity. Knowledge is distributed across networks. In our digital society, the connections and connectedness within networks leads to learning. Siemens argues that a central tenet of most learning theories is that learning occurs inside a person. However, these theories do not address learning that occurs outside of people (i.e. learning that is stored and manipulated by technology). He specifically questions how does learning theory change when information storage, processing, and recall are off-loaded onto devices and through networked connections? In the brain, knowledge is distributed through connections between different regions of the brain and in the networks we form (social and technological) knowledge is distributed through connections between individuals, groups, and devices (Siemens, 2006).

Phenomenology: Phenomenology is actively endorsed by Edmund Husserl. By employing our experiences of perception, thought, memory, imagination, emotion, desire, and volition, Phenomenology studies the intentional structures of consciousness. The goal of phenomenology’s intentionality is to develop: … a complex account of temporal awareness (within the stream of consciousness), spatial awareness (notably in perception), attention (distinguishing focal and marginal or “horizontal” awareness), awareness of one’s own experience (self-consciousness, in one sense), self-awareness (awareness of oneself), the self in different roles (as thinking, acting, etc.), embodied action (including kinesthetic awareness of one’s movement), intention in action (more or less explicit), awareness of other persons (empathy, intersubjectivity, collectivity), linguistic activity (involving meaning, communication, understanding others), social interaction (including collective action), and everyday activity in our surrounding life-world (in particular culture).

Neuroscience: While neuroscience is an emerging field with a vastly changing landscape, few neuroscientific findings have been shown to be fundamental to the way we think and learn. Formation of interconnections between nerve cells has been central to how learning takes place. In 1949, Hebb proposed a principle that “When two neurons fire together the synapses are altered through growth and they will tend to be wired together” (p. 11). Hence, Hebb coined the phrase, “neurons that fire together wire together.” With the progress of advanced imaging technologies, we have made tremendous progress in understanding what happens at a neurobiological level when learning occurs and how it differs with different factors.

This concept map may help us understand the connections between different learning theories. For a better quality please click on the image and it will zoom in and out.

Activity 3: Please choose any one theory of your choice and analyze it. Post a brief note about its strengths and limitations and when could it be best used.

_____________________________________________________________________________

References

Ackermann, E. (2016). Piaget’s Constructivism, Papert’s Constructionism: What’s the difference? (1st ed., pp. 1-11). MIT Media Labs. Retrieved from http://learning.media.mit.edu/content/publications/EA.Piaget%20_%20Papert.pdf

Ertmer, P. & Newby, T. (2008). Behaviorism, Cognitivism, Constructivism: Comparing Critical Features from an Instructional Design Perspective. Performance Improvement Quarterly, 6(4), 50-72. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1937-8327.1993.tb00605.x

Fosnot, Catherine Twomey. Constructivism: Theory, Perspectives, and Practice, Second Edition (Kindle Locations 779-780). Teachers College Press. Kindle Edition.

Siemens, G. (2006). Connectivism: Learning theory or pastime for the self-amused? [Electronic Version]. elearnspace, 1-43. Retrieved September 9, 2007, from http://www.elearnspace.org/Articles/connectivism_self-amused.htm

Snelbecker, G. (1974). Learning theory, instructional theory, and psychoeducational design. New York: McGraw-Hill.