Hello readers!

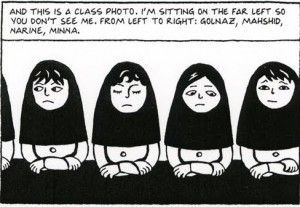

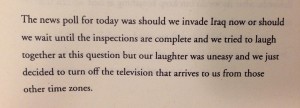

I can hardly believe that we have already reached the time for our last ASTU blog post, so I wanted to take a quick look back at our year. One of the most prominent themes of our class this year was trauma. We read a wide array of what one could call ‘trauma narratives’ that explored the social, personal, cultural, and political factors that traumatic events can have on individuals and communities. For instance, going back to first term, we started with “Persepolis” and explored Marjane’s disheartening upbringing during the Iranian revolution. Then, in “Safe Area Gorazde”, we saw the impacts of the Bosnian War through the eyes of an American journalist. In “Obasan”, we witnessed Naomi’s destructive past that caused poignant impacts to her adult perspective. We read about the deep rooted repercussions that a veteran’s PTSD had on his daily interactions in the short story “Redeployment”. And our past two texts, “Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close”, and “The Reluctant Fundamentalist”, we witnessed the growth of two very different characters in post 9/11 America.

Although the theme of trauma becomes at times extremely heavy and heart wrenching, it is evident that through trauma comes great literature. Not only can trauma narratives provide solace for authors, but they can also give readers a deeper understanding of the human experiences behind the facts and dates of traumatic world events. The traumas experienced by the characters we read about differed immensely in terms of their time frame, scale, and location. However, I think it is safe to say that the characters held the same overarching sentiments of fear and vulnerability. In most cases, this fear was a result of the creation of some sort of social divide. Whether it was the attack on the World Trade Centre, or the construction of Japanese internment camps, the characters we read about were living through trauma created from society’s development of the ‘Other’. After reflecting back, I now see a sort of irony in these trauma narratives: they were based from the establishment of various social oppositions while simultaneously being unified through the raw human emotions felt by the characters. Reading the texts, it didn’t matter where in the world the character lived or what ethnicity they were because we could always relate to their human emotions. In fact, I think the human perspectives in our texts were even more powerful than the various traumas that they were describing.

The impacts of social divides is an idea that we have come back to time and time again throughout all of our courses in the Global Citizens stream. It is also one that is, unfortunately, very relevant to recent current events, such as the bombings in Brussels just a couple of days ago. Traumatic events and attacks such as these are perhaps not easily preventable; however, I believe that literary texts (as well as other forms of self-expression, such as art and poetry) that come out them are necessary in order to voice the emotions and experiences behind such difficult issues. Above all, I think trauma narratives succeed in connecting individuals to form the universal solidarity that today’s world is in desperate need of.

Thanks for reading, and thanks for the great year!

Harnoor

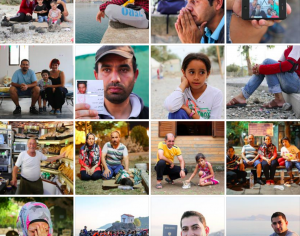

y tend not to make much of an impact on people until their truths are fully realized through a deep emotional connection and understanding. For instance, everyone is aware of the shocking photo of a Syrian toddler who washed up on the shore of Bodrum. This photo spread rapidly on social media and caused an uproar in the general public to increase humanitarian efforts towards the migration crisis. Sadly, there are thousands of children who have reached this same tragic fate; however, this little boy made a larger global impact because of the photo’s horrific and difficult-to-ignore emotional content. Likewise, a humanities website called Human of New York photographed and interviewed several refugees, and the comments on each post are filled with people expressing how this direct interaction with real people behind the crisis have changed their frame of thought towards the issues. Above are examples of HONY’s photographs of refugees during his visit to Greece.

y tend not to make much of an impact on people until their truths are fully realized through a deep emotional connection and understanding. For instance, everyone is aware of the shocking photo of a Syrian toddler who washed up on the shore of Bodrum. This photo spread rapidly on social media and caused an uproar in the general public to increase humanitarian efforts towards the migration crisis. Sadly, there are thousands of children who have reached this same tragic fate; however, this little boy made a larger global impact because of the photo’s horrific and difficult-to-ignore emotional content. Likewise, a humanities website called Human of New York photographed and interviewed several refugees, and the comments on each post are filled with people expressing how this direct interaction with real people behind the crisis have changed their frame of thought towards the issues. Above are examples of HONY’s photographs of refugees during his visit to Greece.