Hello readers,

This past week, my ASTU class has read and discussed a scholarly article called The Texture of Retracing in Marjane Satrapi’s ‘Persepolis’, by Hillary Chute, who is a literary scholar and expert in the genre of graphic narratives. Throughout the article, Chute examines a variety of aspects present in Satrapi’s Persepolis including its feminist standing, the style of its illustrations and how it affects the audience’s interpretation, and the process of “never forgetting” in Marji’s narration (Chute 97).

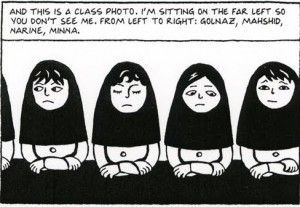

One of the many unique qualities of Persepolis in my eyes is Satrapi’s use of two narrators: Marji, the child protagonist, and Marjane, the older and more experienced narrator. As opposed to being one sole act of recall that we typically see in memoires, Persepolis shows the audience her “state of being of memory”, and her development of perspective as she grows up and reflects back on her previous self (Chute 97). A benefit of experiencing the narrative through a ten-year-old’s eyes is getting to see the simplistic and minimalistic visual interpretations of events that in reality are horrifically traumatic. A section of the article that was of particular interest to me examined the ease in which Marji, the child protagonist, visualizes and stylizes occurrences of horrific trauma so casually. By using black and white, and drawing with clean lines and literal translations, Marji takes violent events that people are not even used to reading about, let alone seeing, and overtly illustrates them with simplicity and innocence. For instance, when Marji learns that one of her prison heroes, Siamak, has been “cut to pieces” (Satrapi 52), the last frame on the page depicts her interpretation of the news which includes a hollow doll-like figure cut precisely into seven even pieces. Examples of these representations of trauma appear consistently all throughout the text and occasionally right in the middle of Marji’s daily personal routine, which emphasizes the eerie ‘normal’ quality of trauma in her everyday life. Surely, events such as torture, executions, bombings, and murder, are not remotely normal, yet the way in which they are presented in Persepolis suggest otherwise. I think Satrapi purposely used uncomplicated drawings to depict these appalling acts of violence to emphasize the normalcy of violence that people often tend to associate with Iran and the Middle East in general.

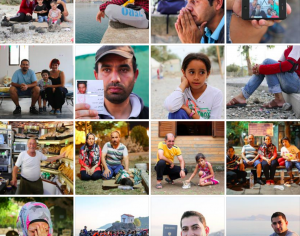

When considering my own exposure to Iran as a North American, non-middle-eastern teenager, I’m bombarded with images of war, poverty, and Islamic extremist groups like ISIS that have been depicted to me through news outlets and other forms of media. Unfortunately, these horrific events have acquired a certain normalcy, and the y tend not to make much of an impact on people until their truths are fully realized through a deep emotional connection and understanding. For instance, everyone is aware of the shocking photo of a Syrian toddler who washed up on the shore of Bodrum. This photo spread rapidly on social media and caused an uproar in the general public to increase humanitarian efforts towards the migration crisis. Sadly, there are thousands of children who have reached this same tragic fate; however, this little boy made a larger global impact because of the photo’s horrific and difficult-to-ignore emotional content. Likewise, a humanities website called Human of New York photographed and interviewed several refugees, and the comments on each post are filled with people expressing how this direct interaction with real people behind the crisis have changed their frame of thought towards the issues. Above are examples of HONY’s photographs of refugees during his visit to Greece.

y tend not to make much of an impact on people until their truths are fully realized through a deep emotional connection and understanding. For instance, everyone is aware of the shocking photo of a Syrian toddler who washed up on the shore of Bodrum. This photo spread rapidly on social media and caused an uproar in the general public to increase humanitarian efforts towards the migration crisis. Sadly, there are thousands of children who have reached this same tragic fate; however, this little boy made a larger global impact because of the photo’s horrific and difficult-to-ignore emotional content. Likewise, a humanities website called Human of New York photographed and interviewed several refugees, and the comments on each post are filled with people expressing how this direct interaction with real people behind the crisis have changed their frame of thought towards the issues. Above are examples of HONY’s photographs of refugees during his visit to Greece.

I think Satrapi’s portrayal of Marji’s perspective has a similar effect as it provides a shocking juxtaposition between the simple drawings and the violence they are producing, rejecting the face that it should be normal at all. Although no horrific and traumatic events, such as the ones that occur in Persepolis, can be adequately visualized, I think the minimalistic and innocent take on the images creates a more powerful effect than a realistic one ever could, as it forces readers to reach for the truth in their imagination. This overt visualization is one of the factors present in graphic novels that challenge the typical characteristics of written narratives.

Thanks for reading!

Harnoor

Works Cited:

Chute, Hillary. 2008. “The Texture of Retracing in Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis.” Women’s Studies Quarterly. Vol. 36(1/2) pp. 92-110

Satrapi, Marjane. Persepolis. New York, NY: Pantheon, 2003. Print.

Stanton, Brandon. “Humansofnewyork.” Humans of New York. Web. 15 Oct. 2015.