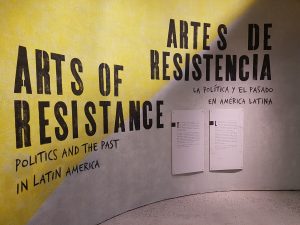

Two weeks have passed since I’ve wrote my previous blog on MOA: the arts of resistance. However, some of the issues that came up from it has continued to bother me.

After receiving the comments on my blog post and reading through the class blogs, I started dwelling on my previous blog post and came to a conclusion that I should write an extension of it.

There were three issues that had me scratching my head.

The first issue was how society tries to shape people in certain ways. In the case of the Mexicans, it was during the Spanish colonization when the Christian missionaries tried to implant the Christian morals and rituals by force. They justified their oppressive methods believing that their ways and their religion was superior and they were civilizing the inferior race. This aspect of Christian injustice had me cringing inside as one who believes in Christ. It is so against what I believe the bible and Jesus taught, that I feel I would have added my voice to rebel against such tyranny.

Secondly, personally, the perspective shift on the concept of “rebellion” itself was quite intense. Growing up in a very conservative Asian Christian household, I always thought being rebellious was negative and bad. Honestly, when I first approached the exhibition, there was a sense of uneasiness in me. However, I’ve now learned that fighting for justice is not always bad after all – that is, when it is really “just” and not just a “justification”.

For instance, being rebellious when you are forced to do something may seem to be justifiable; I can relate to such an experience because when I recall my relationship with my parents during high school, I remember how I would always try to go against their will–although sometimes I knew they were right–just because I was forced to do something. Furthermore, I remember what I learned in my Political Science class recently – about how power doesn’t equal authority, and how power based on force usually doesn’t gain people’s respect. In the end, after some time had passed, I acknowledged that being rebellious wasn’t always “just.”

Thirdly, to elaborate on what I’ve said in my recent post,

“ I could understand the rebellious spirit embedded within the masks. I was surprised by how a single mask could contain such a deep story, and how it could become an agent of telling a nation’s history. “

although now I know the historical context of the devil masks and understand that it was a cultural ritual, I’m still struggling to accept it from a moral perspective.

I heard from a friend that in one of her philosophy classes they were talking about relative morals. If I were in her class, I would ask what attitude and mindset I should have when approaching a culture/belief that contradicts my ideologies or paradigms. Acceptance and tolerance are two different things. Although I understand with my head, I still have the unrelieved emotions that weigh me down in light of the fact that I cannot accept what the mask represents. Should our response to oppression or injustice be the be the opposite of what is being done? The demon masks were the people’s way of rebelling against the Christian/colonial oppression, kind of like a “take that.” But in my opinion, their form of rebellion would actually hurt them more.

In Christianity the cross represents the love and the redemption by god of his people – the story of how Jesus suffered and was persecuted in order to save his people; however, this Is tragically used by those who claimed to be Christians to oppress and enslave others who they looked on as those who needed salvation. One story of salvation was used to oppress, creating a twist from the Christian perspective, and such irony – the story of the demon masks.

http://www.latinamericanstudies.org/aztecs/aztec-religion.pdf

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spanish_missions_in_Mexico