MOA Arts of Resistance: Sympathy for the Devil

From May 17 to September 20, 2018, the Arts of Resistance: Politics and the Past in Latin America exhibition has taken place at the Museum of Anthropology, UBC Vancouver. As it is stated by the homepage of MOA, curated by Laura Osorio Sunnucks, the exhibition illustrates how communities in Latin America use traditional or historical art forms to express contemporary political realities. The exhibition is a unique opportunity for visitors to learn about Latin American politics through the lens of contemporary art. It demonstrates how objects can embody important historical and cultural memories and has the potential to influence how Latin American art and culture are showcased in museums and galleries. (https://moa.ubc.ca/exhibition/arts-of-resistance/)

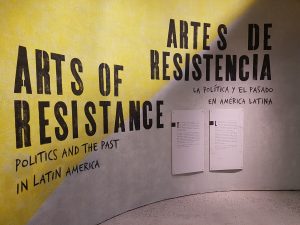

As I entered the museum, I first noticed the several totem poles exhibited straight ahead of the entrance. Although not part of the Arts of Resistance exhibition, the fact that totem poles were also used as significant political instruments, especially as signs of resistance and rebellion, remarkably came to my mind. When I approached the Arts of Resistance exhibition, I noticed the difference in the atmosphere of the exhibition itself; it felt a bit more modern and dynamic than the other parts of the museum. The bright lively yellow sign that indicated the start of the exhibition seemed to well characterize the exhibition as a whole. Furthermore, from the very entrance, I was very pleased to see how all the explanations of the artworks had a separate Spanish translation (instead of French) regarding the fact that the exhibition was depicting the artworks that were deeply rooted to the history of the Latin Americans.

From graffiti to masks and clothes, there was a wide range of diversity of the form of artworks that all commonly embedded stories of resistance in significantly different ways. Personally, among all the pieces of artwork within the exhibition, the demon masks at the “sympathy for the devil” corner were the most strikingly impressive. I was shocked to read the explanation of the artwork, due to the fact that the devil – a morally deviant character – was perceived as a being who offered consolation, listened to the commoners‘ problems, and could respond and act more quickly than God to Mesoamerican natives.

However, after visiting the exhibition, when I researched on the Mexican colonization – on how in the 1500s, Spanish missionaries would ruthlessly and compulsively spread Christianity to the Latin American natives – and learned that the excessive religious passions of the missionaries ended up leading to many side effects in South America: indoctrination, forced labour, epidemics, death, torture, and burning of ancient religions, I could understand the rebellious spirit embedded within the masks. I was surprised by how a single mask could contain such a deep story, and how it could become an agent of telling a nation’s history.

http://www.hani.co.kr/arti/society/life/303135.html#csidxf56915e942a5fb791822938b3d7f54f

https://www.apuritansmind.com/the-christian-walk/easter-the-devils-holiday-by-dr-c-matthew-mcmahon/

http://www.latinamericanstudies.org/aztecs/aztec-religion.pdf

https://www.jstor.org/stable/1008535?seq=3#metadata_info_tab_contents

Hi, this is a comment.

To get started with moderating, editing, and deleting comments, please visit the Comments screen in the dashboard.

Commenter avatars come from Gravatar.