“Most days I wish I was a British pound coin instead of an African girl…

“A pound coin can go wherever it thinks it will be safest. It can cross deserts and oceans and leave the sound of gunfire and the bitter smell of burning thatch behind…

“How I would love to be a British pound. A pound is free to travel to safety and we are free to watch it go. This is the human triumph. This is called, globalization. A girl like me gets stopped at immigration, but a pound can leap the turnstiles, and dodge the tackles of those big men with their uniform caps, and jump straight into a waiting airport taxi.”

-(Little Bee, Chris Cleave)

Even in the post nine eleven era, money opens doors. It goes where people cannot, slipping easily through borders and into new hands. Meanwhile, ordinary people are finding it increasingly harder to travel, let alone immigrate. Our world is purportedly postnational– ethnic diversity abounds- Canadian cities like Vancouver and Toronto, once predominantly white, now have populations made up roughly equally of people of colour and those of European heritage. People move across borders searching for better jobs and quality of life.

Yet nationality is still important, it impacts how you travel, influences how much you pay for school, and determines tax brackets. The costs of living internationally determine who is able to immigrate and succeed in a new country, and the price of immigration is too steep for many to pay. Those with money find fewer barriers than those without.

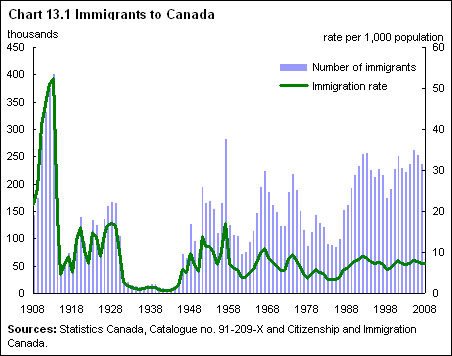

Canada’s immigration rates have stayed pretty consistent through the last 20 years, instead of growing along with the global population and the increasing global interest in immigration.

The last decade has also seen a dramatic increase in migratory workers searching for higher paying jobs in westernized nations, but Canada’s population of migrant workers is low. (Although to be fair, so is the USA’s and the UK’s. Source: January 2014 article in National Geographic on migrant workers) The countries with the largest migrant labour populations are mostly in the Middle East.

Although it is, of course, entirely speculation, I sometimes wonder if our static immigration rates and low migrant labour populations have something to do with white xenophobia. We’re all a little uncomfortable with those that are different from us, unless, as previously mentioned, they have money (we’ll let that rest for now). And while our ‘multicultural,’ ‘postnational’ culture is comfortable with certain markers of difference, there is a limit to which we tolerate it. A man who drives badly is just a bad driver, but we all know the stereotypes that are muttered when the idiot in the other car is a woman, elderly, or someone who looks like they might be an immigrant. As Oku muses in the novel, a white man caught doing the same questionably legal things he and other black Torontonians might would be let off with a warning, rather than incarcerated (even if only for a night). Superficially we aren’t racist, we ‘don’t see culture’, we’re as happy to see an African girl with dark skin as we are to see a British pound coin.

But as Little Bee elaborates in the first chapter of Chris Cleave’s novel (which I quoted above- you should read it by the way, it’s great), stigma against outsiders is determined by more than appearance. When those we see as outsiders behave differently than we do, follow different social cues, talk differently, or do things we find questionable we judge them more harshly, we ostracize them. When an African girl (like Little Bee) has a strange name, a different accent, and not a penny to her name we are less welcoming to her than to another dark skinned woman. Being labeled ‘eccentric’ is a luxury only afforded to the wealthy or white.

So sure, western society isn’t xenophobic. We’re only xenophobic when you’re not like us…

I think this is why Brand’s novel is so important to our society today. A lot of people have expressed frustration with the immaturity of Brand’s characters, as if they are somehow dramatically different from the people we know in real life. But honestly, how many of us thoroughly enjoyed The Catcher in the Rye? How is self-centric, vapid, clueless Holden Caufeild any different from Brand’s four young-adults? Are we willing to be more forgiving to him because he fits the other molds (white, wealthy, male, cis-gendered, straight) we’ve established for people we’re willing to like? And why are we so desperate to see people from other circumstances portrayed in the way Quy describes near the beginning of the novel?

At the risk of sounding pretentious, I suspect that those who don’t like Brand’s novel dislike it because they are either unwilling to consider the questions her writing raises or are made profoundly uncomfortable by them.

Food for thought.