Migrant Foodways: the Story of Teiji Morishita

by Gabriel Lee

In 1920 Teiji Morishita emigrated from Japan to Canada joining his sister in Vancouver BC [1]. He began working at the Ebisuzaki dry goods store. This store had stood on Powell street for a generation selling goods imported from Japan to the Japanese community on Powell street [2]. This short essay intends to look at the kinds of goods imported to the store and how those goods reflect the kinds of transnational linkages described by Elizabeth Zanoni’s book, Migrant Marketplaces.

A Portrait of a Man (Teiji Morishita) Standing Outdoors: Raymond, AB, 1943. Source: 1943.2011.79.4.1.4.50, Morishita Family Collection.

Elizabeth Zanoni’s book Migrant Marketplaces creates an analytical framework with which we can view migration. These migrant marketplaces that she analyzes show the effects of government policy from both the host country and the sending country [3]. This kind of framework is an interesting way of viewing migration in a more holistic sense as it shows how both countries are involved in the journey and economic success of an immigrant/emigrant. This can also be described as the transnational global economy that the world was becoming around the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries.

The Ebisuzaki store existed right on the edge of that turning point and can serve as a new site with which we can test Zanoni’s hypotheses.

The Ebisuzaki store served the interests of the community best through participation in transnational markets. By bringing in cultural goods for sale from Japan the store fits with Zanoni’s ideal of transnational marketplaces. Right up until their closing in 1942, the store was operating and selling goods they had imported [4]. Teiji Morishita, at that point the sole owner of the store, kept fairly well-documented records of what was sold/imported on certain weeks.

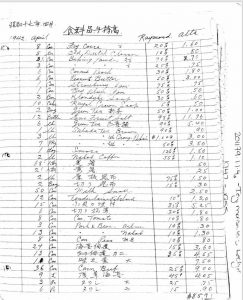

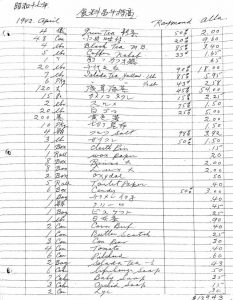

A Selection of Balance Sheets

Source: 1942-55 2011-79-1-1-4a, Morishita Family Collection

The store’s records for April show that they had made deliveries to Raymond, Alberta. They delivered essentials like baking powder or canned fruits [5]. What is interesting are the lines that Teiji wrote in Japanese. Those lines are the records of imported goods. One kind of imported good they sold was kombu. Kombu is a kind of dried seaweed used in traditional Japanese cooking. Many soup-based dishes require it to make the dashi or broth [6]. The store sold two kinds of kombu, “seven swords (七刀)” and “atsuita.” [7] Given that the name “seven swords” appears next to other goods on Teiji’s delivery list it seems as if that particular kombu is a brand [8]. The name “seven swords” didn’t make an appearance on any of the import documents that Teiji kept. This could mean that the seven swords brand/company was located within BC and the store didn’t need to import the products themselves. Whether the seven swords brand is an international brand or not it still shows how the Ebisuzaki store engaged with and helped perpetuate the migrant marketplaces that Zanoni discusses. The “atsuita” kombu is also interesting since it seems to refer to a specific kind of seaweed. This seems like it might be a kind of kombu rather than a brand given that there is a kind of kombu called atsuba kombu. Atsuba kombu is a kind of kombu that is harvested in Hokkaido [9]. If the “atsuita” kombu is Teiji’s version of atsuba kombu then this further shows the transnational markets that Teiji participates in given the fact that the first surge of colonization in Hokkaido ended thirty years prior [10]. If not it still shows how the Ebisuzaki store bought and sold different kinds of goods from across the globe thereby fitting into these transnational economies that Zanoni describes.

Sheets of Kombu

Source: Wikimedia Commons

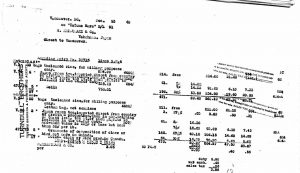

Another aspect of migrant marketplaces Zanoni looked at was the prestige of authenticity. She pointed out how the Italian dreams of economic colonialism needed migrants to be the buying and selling Italian goods made in Italy. These kinds of dreams were thwarted by the actions of protectionist policy in the Americas and were further stymied by the actions of the immigrants creating “tipo” goods as substitutes [11]. Tipo goods are the products of Italian immigrants abroad creating Italian-style goods produced in other countries. The Ebisuzaki store while not using the term tipo to describe their homemade goods the store buys into some degree of authenticity as a value. This can be seen in the customs documents kept by Masataro Ebisuzaki. Ebisuzaki kept different documents recording his dealings with the company Turnbull Brothers, a customs agency. One particular receipt stands out which is for December 23rd which lists a few items that were given extra duty fees that Masataro would have to pay [12].

Receipt Regarding the Cargo of the Tatuno Maru, December 23, 1940

Source: 2011:79:3:1, Morishita Family Collection

The most important ones on the list would be fees for Japanese green tea and rice. The green tea deals with Zanoni’s idea regarding the importance of authentic goods versus those Japanese-style goods made by other countries. Masataro made a conscious decision to buy green tea from Japan and in doing so participated in Zanoni’s transnational marketplace. He also helped promote the Japanese state through economic exchange by selling specifically Japanese green tea, another aspect of Zanoni’s description of styled goods vs authentic goods. The rice could fit into Zanoni’s framework in a few different ways. The Turnbull Brothers receipt says that the rice is “for milling purposes only.” [13] Teiji kept a recipe detailing how the Morishitas made miso and one of the ingredients in malt rice which can be made with unmilled rice [14]. Rice didn’t turn up on any of the other documents so either its sale was kept on a separate document that was lost or it was used for personal consumption. If it was used for personal consumption that shows how single immigrant households simultaneously participated in the creation of tipo goods (creating their miso instead of buying miso from Japan) while also still placing value on authenticity (the importing of Japanese rice to create their miso). Even if the rice wasn’t used for the creation of miso it still shows the value of authenticity in creating and maintaining these transnational trade routes.

The Ebisuzaki store serves as a great research site for how migrant groups participate and perpetuate transnational trade. From the store’s importing documents we can learn about how migrants participate in the larger aims of their governments(the potential role of Hokkaido in sourcing kombu) to how they place a premium upon authenticity (the import of Japanese green tea). These documents also show how migrants create their own goods and influence their new cultures.

References

[1] “Biography of Teiji Morishita.”

[2] “Biography of Teiji Morishita.”

[3] Elizabeth Zanoni, Migrant Marketplaces: Food and Italians in North and South America (Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2018). 3

[4] Food Balances Shipments to Raymond, AB for April Showa year 70, April 1942. MS90, Folder 1, Teiji Morishita 1942-55 2011-79-1-1-4a, Morishita Family Collection. Nikkei National Museum & Cultural Centre, Burnaby, British Columbia.

[5] Food Balances Shipments to Raymond, AB for April Showa year 70, April 1942. Morishita Family Collection

[6] “Konbu,” Eat-Japan, accessed February 14, 2022.

[7] Food Balances Shipments to Raymond, AB for April Showa year 70, April 1942. Morishita Family Collection

[8] Food Balances Shipments to Raymond, AB for April Showa year 70, April 1942. Morishita Family Collection

[9] “Atsuba Kombu Seaweed from Hokkaido,” Nishikidori, accessed February 14, 2022.

[10] Sergey Viktorovich Tkachev, Sergey Vasilyevich Ryazantsev, and Natalia Nikolaevna Tkacheva, “The Beginning Stage of the Japanese Colonization of Hokkaido (1869-1919),” Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 2015.

[11] Elizabeth Zanoni, 74

[12] Receipts Regarding the Cargo of the Tatuno Maru December 23, 1940. MS90, Folder 8, Accounts Payable 2011:79:3:1, Morishita Family Collection. Nikkei National Museum & Cultural Centre, Burnaby, British Columbia.

[13] Receipts Regarding the Cargo of the Tatuno Maru December 23, 1940, Morishita Family Collection.

[14] Recipe for Miso and Recipe for Hotcakes. MS90, Folder 1, Teiji Morishita 1942-55 2011-79-1-1-4a, Morishita Family Collection. Nikkei National Museum & Cultural Centre, Burnaby, British Columbia. : “Kome Koji,” Eat-Japan, accessed February 14, 2022.

Bibliography

“Atsuba Kombu Seaweed from Hokkaido.” Nishikidori. Accessed February 14, 2022.

“A Portrait of a Man(Teiji Morishita) Standing Outdoors; Raymond, AB.” Morishita Family Items, Family photographs, 2011.79.4.1.4.50, Morishita Family Collection. Nikkei National Museum & Cultural Centre, Burnaby, British Columbia

“Biography of Teiji Morishita.” Nikkei National Museum & Cultural Centre, Burnaby, British Columbia.

“Kome Koji.” Eat-Japan. Accessed February 14, 2022.

“Konbu.” Eat-Japan. Accessed February 14, 2022.

Morishita, Teiji. MS90, Folder 1, Teiji Morishita 1942-55 2011:79:1:1:4a, Morishita Family Collection. Nikkei National Museum & Cultural Centre, Burnaby, British Columbia.

Tkachev, Sergey Viktorovich, Sergey Vasilyevich Ryazantsev, and Natalia Nikolaevna Tkacheva. “The Beginning Stage of the Japanese Colonization of Hokkaido (1869-1919).” Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 2015.

Turnbull Brothers. Receipts regarding the cargo of the Tatuno Maru December 23, 1940. MS90, Folder 8, Accounts Payable 2011:79:3:1, Morishita Family Collection. Nikkei National Museum & Cultural Centre, Burnaby, British Columbia.

Wiegand, Alice. Kombu. Wikimedia Commons, 2006. Accessed March 27, 2022.

Zanoni, Elizabeth. Migrant Marketplaces: Food and Italians in North and South America. Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2018. Accessed February 14, 2022. ProQuest Ebook Central.