You might wonder why it is important for me to go into things like binding, covers, etc. Like I said before, this bit of the research can give me the tools to gauge what kind of market this book was aimed at. Bear in mind that the question is, “Why was the book so popular?”. This section could very well become the reason why one theory seems more plausible than another one to answer the question: “A binding’s quality may signify the regard in which the text is held, or the level of use it is expected to have, or it may say something about the owners taste and standing.” This quotation is from English Bookbinding Styles.

This post will be divided into two parts. Part I will look at the the physical aspects of the book. Part II will look inside the book. Let’s begin!

Part I: The outside of the book

The Cover:

By looking at the cover, I am interested in answering two questions:

- What is the cover made out of?

- What is that design on the cover?

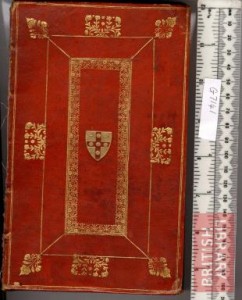

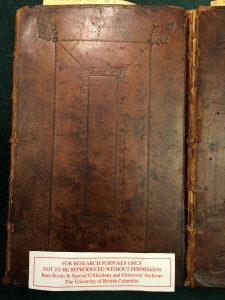

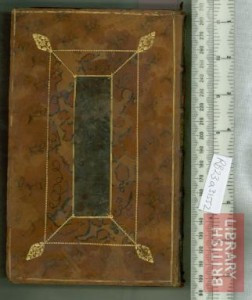

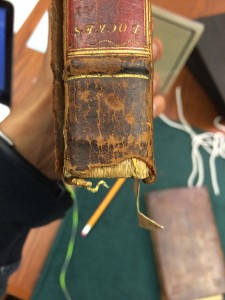

At first glance, it seems that the cover is made out of some kind of leather based on the colour and feel of it. This leather has been pasted over the board and spine of the book. Before answering what the cover was made out of, I am going to turn to the ornamentation of the cover. The decoration seems quite simple; however, the spine is better decorated:

It does not seem like the person that had the book bound spent a lot of money on its decoration. If the person did not spend a lot on the decoration of the book, it could point me towards what kind of leather was used. At the time, the leather could be from either goatskin, sheepskin, or calfskin.

Goatskin would have to be imported from Turkey, which would have been expensive (Pearson 19). Going through the British Library Catalogue and looking for covers around the same era with the same ‘panel design’ on the cover, I found that most of the covers were made out of goatskin. But most of those covers were also red in colour and looked more ornate:

Let’s now look at something from around the same period in calf:

Published in 1706. This one is more what I’m looking for.

Published in 1706. This one is more what I’m looking for.

Pearson writes in English Bookbinding Styles, “It [calf] was usually dyed some shade of brown and, although it could be produced in other colours, English bindings of this period in red, green and other hues will more commonly be found to be goatskin” (18). Our leather is also ‘brown’ and resembles the picture right above this paragraph. It wouldn’t be unfounded to say that the leather covering is made from calf, which answers the first question. (It was hard to find anything about sheepskin, in case you caught on).

Now we can turn to the second question, which I have already started answering. The design is a ‘panel design’. Pearson writes, “The centre and corner idea remained current throughout the Restoration period and beyond…” (73).

A close-up of the cover:

There are a lot of floral/foliage designs that have been pressed into the cover. Pearson notes that this kind of design is prevalent in The Restoration (73). But I did state that the spine seemed to be more ornate. Let’s go back to that:

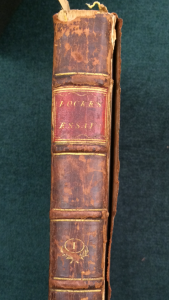

There is some work done in gold

There is some work done in gold

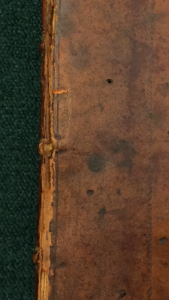

The spine has a ‘raised band’, which is caused by the sewing. The ‘inside’ of the book that makes up the text is referred to as a bookblock. The bookblock is made up of sections:

You can see all of the sections at the bottom of the book

You can see all of the sections at the bottom of the book

These sections were sown together, which in this period would have been done by cord (Pearson 102). This sewing shows as ‘raised bands’ on the spine. Our book has five of these raised bands. The book could be given further stability by allowing the sewing to run into the cover of the book. You can see this in our book here:

Turning back to the spine, there are compartments caused by the raised bands. There is a title on one of these compartments. The practice of putting titles on the spine (Spine Labelling) started happening when shelving practices changed to that of shelving books with the spine facing outwards (107). The edges of these compartments are further decorated with ‘narrow gold fillets’. However, there is not much work done on the spine. Another look at the spine reveals the endband:

The little thing hanging off with some cord sticking out

The little thing hanging off with some cord sticking out

These endbands also became prevalent with new shelving practices. The book would now be reached for by tugging at the spine. The endbands would give the spine extra support.

Our endband seems quite ordinary, in terms of its lack of ornamentation. Compare this endband to one on another copy of the Essay that we have at the library:

Clearly a little more work was put into this one

Clearly a little more work was put into this one

So far we have covered: the cover, the cover design, sewing, spine, and endbands. All of the evidence so far points towards this being a rather ordinary edition. We can now turn to what’s going on inside the book.

Part II: Inside the book

The book is in two volumes:

The edition that I am looking at has Volume I published in 1716 and Volume II published in 1715. However, both Volumes are continuations of each other, since the index at the end of Volume II refers to the correct page numbers in Volume I. The first volume was published by John Churchill and the second one by John Churchill and Awnsham Churchill. They were both brothers, and John was the younger one. I will come back to the Churchills a littler later.

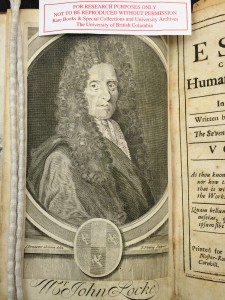

The book begins with an author portrait:

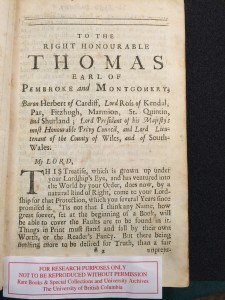

The book then has a dedication to “Thomas Earl of Pembroke and Montgomery”:

This ‘Thomas’ is Thomas Herbert whom Locke met Montpellier, France. Locke travelled in France from 1675 to 1679, where he met Herbert. Herbert had undertaken a “three-year tour of France and Italy”, which is when he met Locke. This all recorded in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

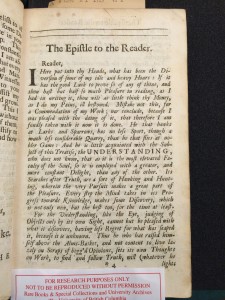

Moving on, we then have “The Epistle to the Reader”:

This edition also has a lot of footnotes:

The footnote states: “The Doctrine of Identity and Diversity, contained in this Chapter, the Bishop of Worcester pretends to be inconsistent with the Doctrine of the Christian Faith…”

What is going on here? The footnote refers to an idea of Locke that was challenged to be inconsistent with the Christian Doctrine. However, the editor of this book, who is also the publisher and most likely Awnsham Churchill, diffuses this claim in the footnote. There are still a lot of questions to be asked here: When did this editorship begin? Why was it done? Did Locke approve of it? However, these question cannot be answered from within the book. This, therefore, segues quite well into the question: What surrounds this book?