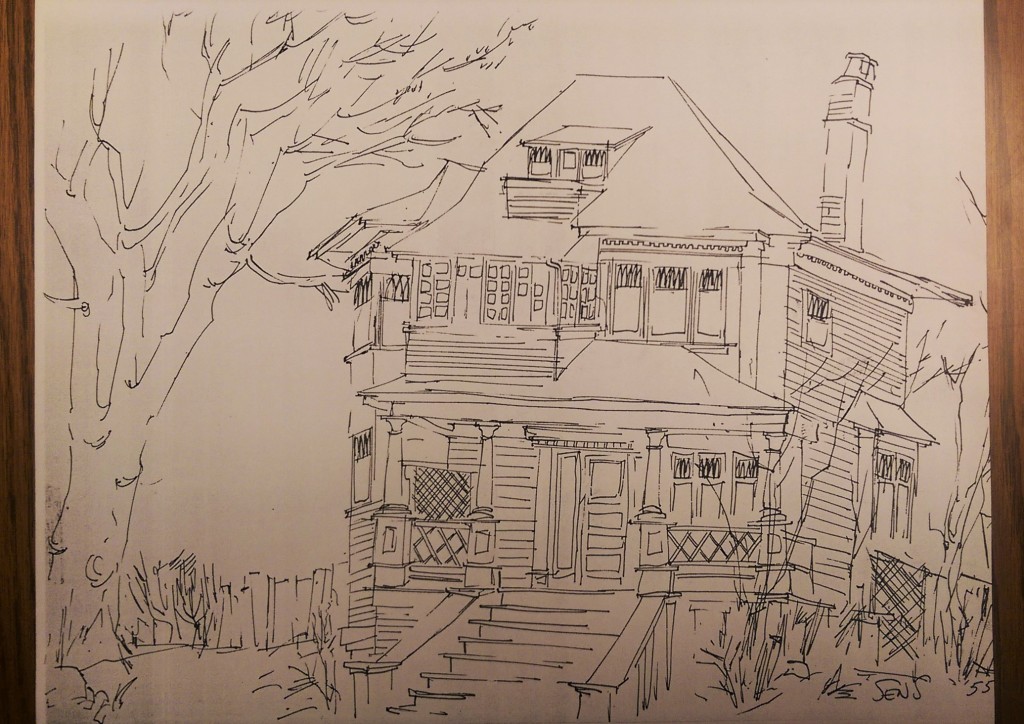

Before the development of today’s computer animation, where illustrations are either scanned into or drawn directly in a computer software, there was traditional animation. Al Sens transitioned seamlessly between the artistic roles of cartoonist to an animator because his animation technique essentially boiled down to a series of cartoons (each new drawing slightly altering from the previous drawing), each photographed onto a film reel (each photograph on the film is called a frame) that, when played, created the illusion of movement. Hand-drawn animation techniques are done on an animation stand, a flat table-top with an overhanging animation camera to photograph each frame.1

By and large, Sens’s films were made using the technique of cel animation. A cel (or celluloid) is a drawing or photocopy on a transparent sheet of acetate. A cel can contain characters, text/writing, or foreground details of the setting, and different combinations of cels can be stacked on top of each other. Cels (or combinations of cels) are accompanied by an underlying background image.2

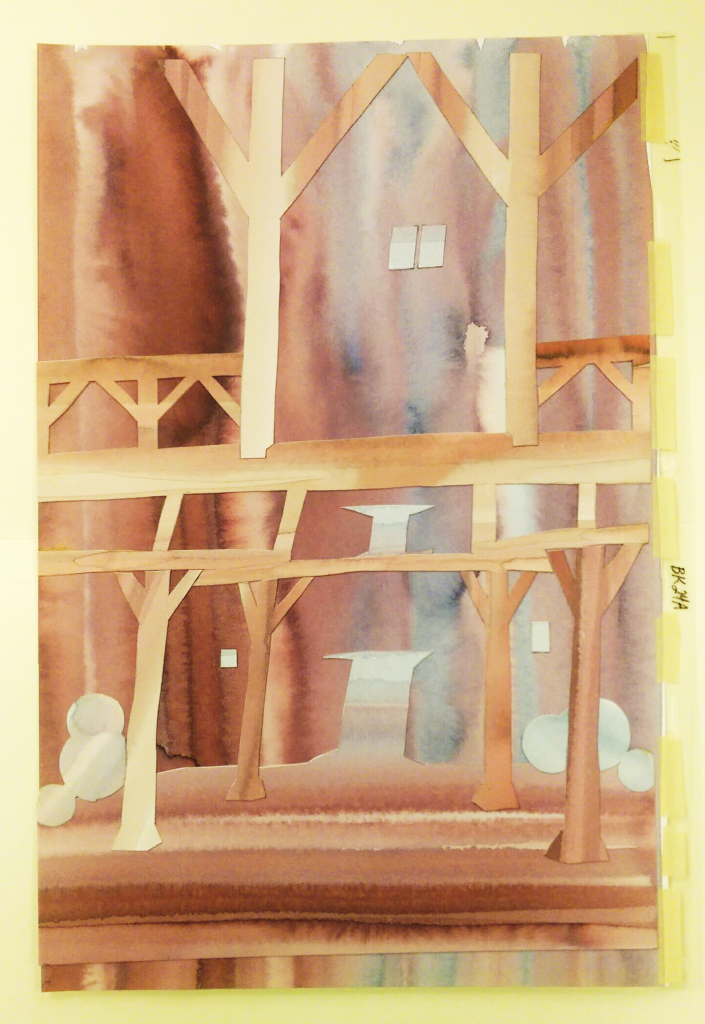

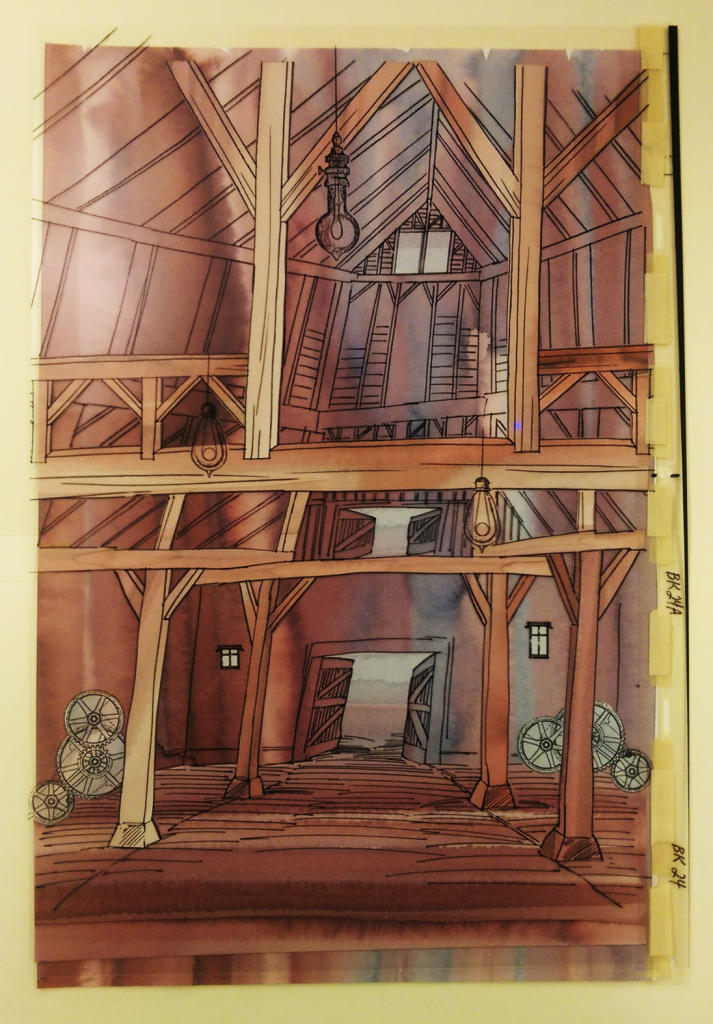

Sens’s backgrounds held at RBSC were predominantly done in watercolour paints. A base watercolour sheet was covered in pieces of cut-out paper (also painted in watercoulour) that were glued on. These backgrounds were then covered by an acetate cel on which black lines sharpened and filled in the background, as well as added some foreground elements. See, for example, these images (with and without the acetate cel layer) of one of Sens’s backgrounds of the interior of a factory:3

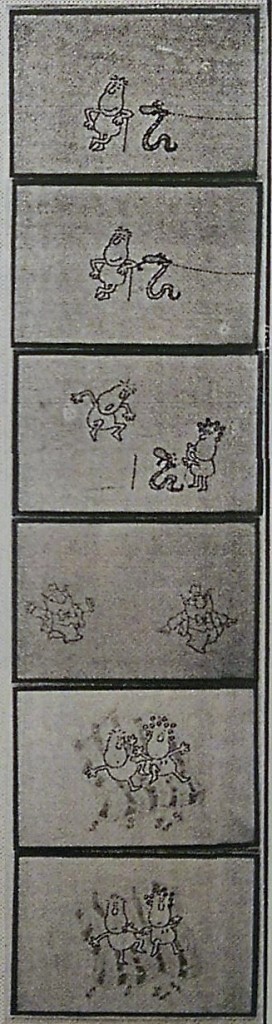

Cels need not be limited merely to black lines, they could also consist of coloured paints, such as the example below. A number of Sens’s political films contain anthropomorphized animals. One series of developed and undeveloped photographs I found in the archives demonstrates the effect of stacking different cels containing different characters on top of a background. Notice how the background remains the same as the presence of the various characters changes:4

- For a more complete list of different animation techniques and the history of animation development, visit the Wikipedia article, “Animation:” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Animation#Traditional_animation.

- I consulted the above Wikipedia article and the following book from Sens’s archives in learning more about cel animation: Trojanski, John and Louis Rockwood. Making it Move: Instructor’s Manual. Dayton, OH: Pflaum/Standard, 1973. Print. Al Sens Collection. RBSC-ARC 1729, box 2, folder 4. Rare Books and Special Collections, Irving K. Barber Learning Centre, University of British Columbia, Vancouver.

- Sens, Al. Factory interior background [animation celluloids]. [19–?]. Al Sens Collection. RBSC-ARC 1729, box 3, folder 10. Rare Books and Special Collections, Irving K. Barber Learning Centre, University of British Columbia, Vancouver.

- Which film these images are from is not made clear in the archives. Perhaps Sens’s “Problems on an Imaginary Farm” (1979)? Perhaps “Political Animals” (1992)? Sens, Al. [19–?] Al Sens Collection. RBSC-ARC 1729, box 3, folder 2. Rare Books and Special Collections, Irving K. Barber Learning Centre, University of British Columbia, Vancouver.