Julia Sande

Although the concrete harms caused by corruption are not always obvious, it is not a victimless crime. Corruption, which is the abuse of entrusted power for private gain, can have far-reaching impacts that cost societies and individuals their freedom, health, money, and lives.

Transparency International categorizes the costs of corruption as political, social, economic and environmental. When politicians engage in corrupt behaviour, it undermines democracy and the rule of law, which leads to a loss of legitimacy in institutions, making it very difficult to establish accountability. Corruption greatly weakens society’s trust in institutions and political leadership, which results in a skeptical or even apathetic public that becomes less likely to challenge corruption, thereby allowing corrupt acts and behaviours to continue in perpetuity. Perhaps most intuitively, corruption depletes national wealth and may divert funds away from services that are beneficial to communities, such as the building of schools and hospitals, which may constitute a violation of citizens’ economic and social rights. Finally, corruption can lead to devastating environmental impacts when legislation and regulations aren’t enforced, and ecological systems are ravaged with impunity.

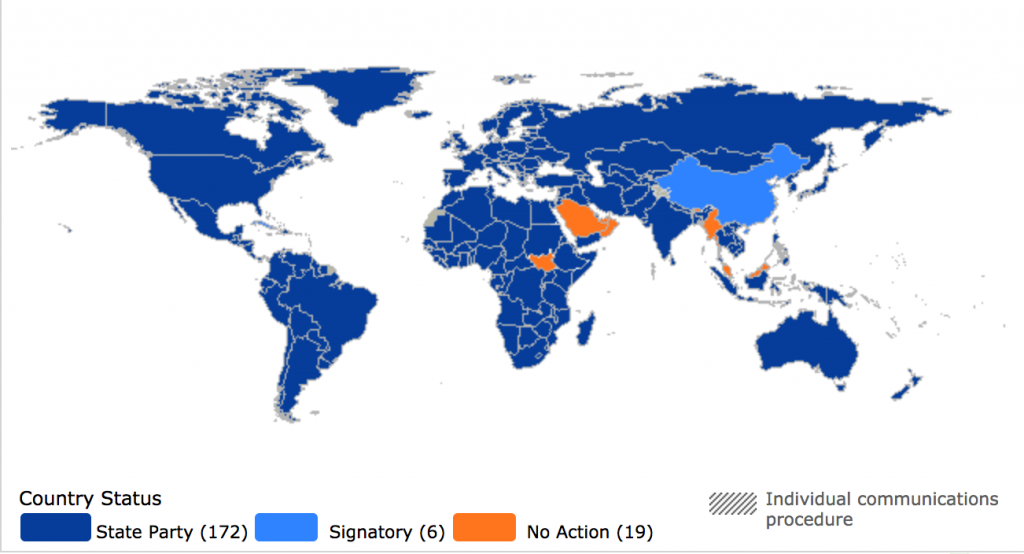

The United Nations Human Rights Committee (“UNHRC”) is well positioned to target corruption at the international level. The UNHRC is the treaty body that oversees the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (“ICCPR”), which is almost universally ratified with 172 State Parties, as well as six additional signatories. The UNHRC is made up of independent experts who monitor the implementation of the treaty, and are thus poised to address the way in which a State’s corrupt act results in violations of the ICCPR.

During its consideration of Bulgaria’s 4th periodic report in October 2018, the UNHRC raised four issues where a link between corruption and a human rights violation was apparent.

The Committee expressed concern over reports of police brutality, which violates multiple articles of the ICCPR: Article 7 on the right to be free from cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment; Article 10, which provides protection for those detained and imprisoned; and Article 2 on the right to equality, which is implicated when police violence is directed at individuals from specific communities. While Bulgarian law technically prohibits police brutality, corruption in oversight institutions has led to impunity for police. From 2017 to mid-2018, only three disciplinary punishments were imposed for the unlawful use of force. The lack of disciplinary action has promoted public distrust and fostered reluctance to report violent incidents. This has had a marked impact on migrant and Roma communities, which are particularly vulnerable to police brutality but less likely to lodge a complaint due to fear of reprisal, resulting in an ongoing cycle of corruption in law enforcement.

The UNHRC also noted that the Bulgarian Prosecutor General has extensive powers and privileges, but ineffective accountability mechanisms to keep those powers in check. While the Supreme Judicial Council can remove the Prosecutor General for committing serious crimes, the Council has no independent fact-finding capacity and thus would have to turn to the prosecution service to investigate itself. Such lack of accountability may lead to a violation of the right to a fair trial, which is protected by Article 14 of the Covenant. The lack of accountability would have great political costs, as the rule of law is undermined when the Prosecutor General operates above the law.

The UNHRC welcomed Bulgaria’s adoption of an anti-corruption and asset forfeiture act, which established a single anti-corruption commission. This law, however, does not allow for anonymous complaints by third parties, which is a major barrier to its use, as many Bulgarians are distrustful of Bulgarian state institutions and might be unwilling to submit complaints due to fear of reprisal. If this law is not effectively used by society, high-level officials with access to public funds can deplete national wealth, causing significant economic costs across the country. If the depletion of national wealth becomes so severe that governments cannot ensure access to essential goods, which then prevents individuals from enjoying their lives with dignity, it may violate the ICCPR’s Article 6 on the right to life.

Finally, the Committee addressed the troubling trend of increased threats and attacks on journalists in Bulgaria. The arrests of journalists investigating corruption, intended to discourage them from continuing their work, are a clear violation of Article 19, which protects freedom of expression.

As can be seen by Bulgaria’s recent review by the UNHRC, corruption is not a victimless crime – it violates individuals’ internationally protected human rights. The Committee should ensure it consistently conducts its functions, including State party reviews, with awareness of any underlying corruption, so it can explicitly highlight the causal link between corrupt State acts and violations of the ICCPR. Notably, Articles 2, 6, 7, 10, 14, and 19 can all be undermined by corruption. Through such scrutiny, the Committee can draw international attention and potential political pressure from other countries, which can encourage states to act with transparency and in a manner that does not violate rights.

Corruption is highly relevant to the UNHRC’s work and the rights protected by the ICCPR and other international treaties. The Human Rights Committee should use its platform to promote human rights by explicitly identifying and condemning corruption.

Julia Sande is a second-year student at the Peter A. Allard School of Law. As a clinician in the International Justice and Human Rights Clinic, she is currently supporting the United Nations Human Rights Committee on a wide range of issues.