Ashley Ahluwalia

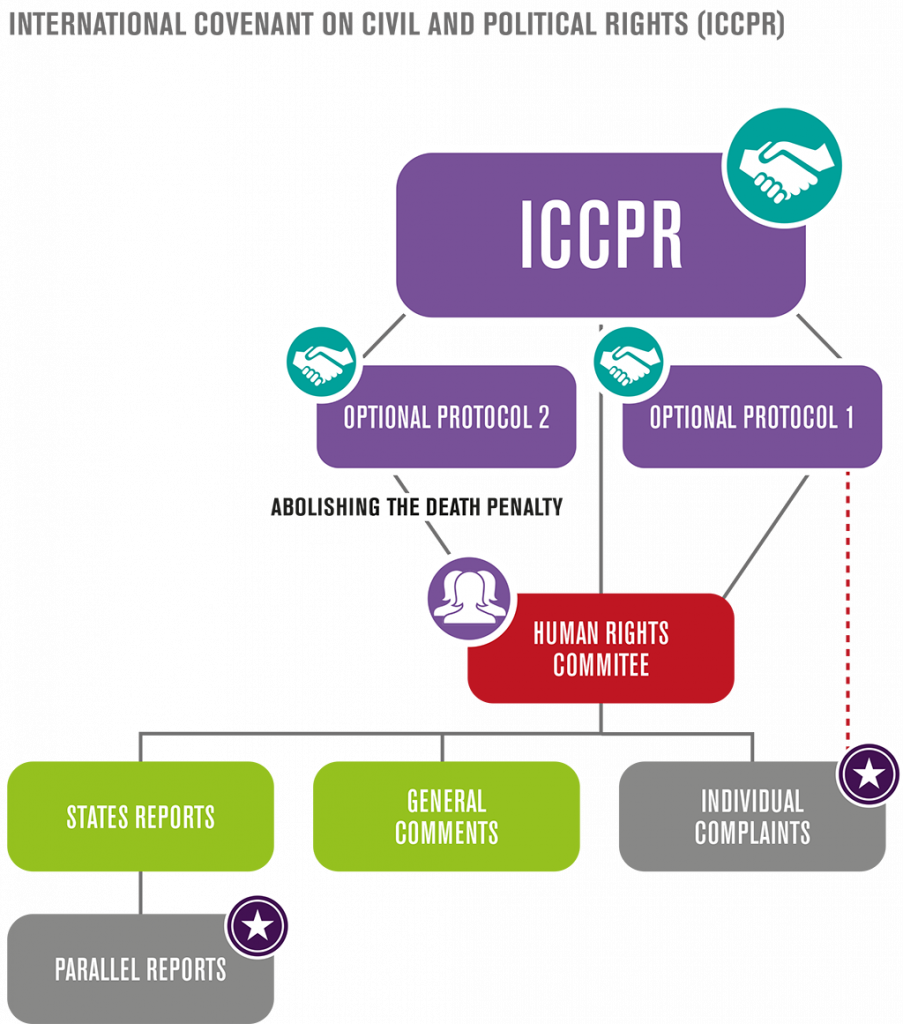

The Human Rights Committee (the “Committee”) is the United Nations (“UN”) treaty body that monitors implementation of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (“ICCPR”) by countries who have signed on. All participating countries must send the Committee regular reports on the steps that they have taken to fulfill the human rights set out in the treaty. The Committee holds sessions where it examines the reports of countries selected for review. Usually, the review proceeds as a constructive dialogue between the Committee and the relevant State’s delegation. A challenge facing the Committee, however, is that some countries fail to submit a report, or simply don’t show up to participate at their review. Some countries are overdue in submitting their reports by ten or more years.

To address this problem, the Committee adopted a “Review Procedure”, which allows them to consider the situation in a country at one of its sessions in the absence of a report or a delegation. In these circumstances, the Committee conducts the review based on the available information provided by sources such as national human rights institutions, government organizations, UN treaty bodies, and the media.

It is important to consider whether reviewing a country without a report or delegation is beneficial. There are many ways in which the Review Procedure allows for positive change. First, and perhaps most obviously, it provides a way for the Committee to consider the implementation of the ICCPR in States that do not comply with their reporting obligations. While such reviews are more limited than those in which the country participates, they nonetheless provide an international forum for assessing what has been achieved and what remains to be done in order to promote and protect human rights. It also serves to hold the country accountable for human rights violations that it may be attempting to conceal.

Second, the Review Procedure encourages participation from countries that have not complied with their reporting obligations. There have been instances where countries, having been notified that their human rights record is scheduled to be scrutinized in absence of a report, have elected to submit a report and/or send a delegation to engage in dialogue with the Committee. For example, the Committee’s decision to proceed with its scheduled reviews of Central African Republic, Kenya, Barbados, and Nicaragua, despite non-participation by the various governments, resulted in prompt submission of the countries’ overdue reports.

Finally, the Review Procedure signals that all countries who have signed on to the treaty will be treated equally, and sends a message that the Committee will not tolerate non-compliance with ICCPR obligations. Such a perception may encourage countries that do report and participate in Committee sessions to continue to take their obligations seriously.

Although the Review Procedure does achieve the above-noted positive results, it also has significant disadvantages. First, it does not always prompt compliance. The approach has not been effective with The Gambia, for example, which has been overdue in submitting its second periodic review since 1985. The Committee examined The Gambia in absence of a report or delegation in 2002. Despite being notified of the review, The Gambia did not submit a report or send a delegation. In 2009, after numerous attempts to encourage participation, the Committee declared The Gambia to be in breach of its reporting obligations.

Second, several aspects of the Review Procedure oppose the purposes of reporting. According to the UN Secretariat’s Guidelines on an Expanded Core Document and Treaty-specific Targeted Reports and Harmonized Guidelines on Reporting under the International Human Rights Treaties (“Harmonized Guidelines”), one of the purposes of reporting is to review implementation of human rights at a national level. To fulfill this purpose, the reporting process should “encourage and facilitate, at the national level, popular participation, public scrutiny of government policies and constructive engagement with civil society”. However, the Committee can only privately review a country without a delegation present, which prevents public scrutiny of the human rights situation in the country. Public scrutiny is an essential mechanism for holding a country accountable for its actions and/or inactions.

The Harmonized Guidelines also express that a purpose of reporting is to facilitate constructive dialogue between treaty bodies and countries at the international level. Conducting a review without a delegation prevents the Committee and the country from engaging in constructive and meaningful dialogue. The Review Procedure is thus one-sided: the Committee evaluates the country based on information it gathers from external sources and internal material from other treaty bodies.

A third potential issue with the Review Procedure is the ability of the Committee to adequality familiarize itself with the country’s human rights situation without information from the country itself. In certain countries, there is minimal information available from external sources. A lack of adequate information could negatively impact the quality of the Committee’s consideration and impair its ability to produce potentially effective recommendations.

Overall, the benefits of the Review Procedure outweigh the shortcomings, as it allows the Committee to examine the implementation of the ICCPR in non-participating countries, prompts non-participating countries to fulfill their reporting obligations, and encourages participating State Parties to continue to take their reporting obligations seriously. The positive effects of the Review Procedure were again seen at the Committee’s 124th session in October 2018. Saint Vincent and the Grenadines’ (“St. Vincent”) was scheduled for review, but did not submit a periodic report and indicted it would not be sending a delegation. The Committee opted to proceed to consider St. Vincent as scheduled under its Review Procedure. In response, St. Vincent sent the Committee a request to postpone the review and pledged to submit a report within months. The Committee accepted the request and moved St. Vincent’s review to the following session in March 2019. St. Vincent has since confirmed that they will be sending a delegation to participate in this month’s upcoming review.

This situation provides another clear example of the benefits of the Review Procedure, namely its success in encouraging participation from countries. Consequently, the review of St. Vincent at the Committee’s 125th session will likely proceed with the Committee more accurately informed on the country’s human rights situation, thereby enabling a more meaningful dialogue and resulting in sounder recommendations. And, of course, the ultimate beneficiaries will be citizens and civil society across St. Vincent, who will have clearer benchmarks to which they can hold their government accountable.

Ashley Ahluwalia is a third-year law student and clinician with the International Justice and Human Rights Clinic at the Peter A. Allard School of Law at the University of British Columbia.