by Andy Wu

by Andy Wu

On June 27, 2019, the Supreme Court issued its decision on Rucho v. Common Cause, a landmark case regarding partisan gerrymandering. The 5-4 decision split the conservative and liberal justices, and ruled that the federal courts cannot review allegations of partisan gerrymandering. Chief Justice John Roberts, siding with the majority, expressed opposition to partisan gerrymandering, but also stated that to stop partisan gerrymandering is the prerogative of the states and Congress, not the federal courts. (Chung & Hurley, 2019)

John Roberts, along with the rest of the Conservative bloc, prefaced the decision by saying that the federal courts are charged with resolving cases and controversies of judicial nature. In contrast, questions of a political nature are “nonjusticiable,” and the courts cannot resolve such questions. Partisan gerrymandering predated the birth of the nation, and, aware of this occurrence, the Framers of the Constitution chose to empower state legislatures, “expressly checked and balanced by the Federal Congress” to handle these matters. While federal courts can try to answer “a variety of questions surrounding districting,” including racial gerrymandering, it is beyond their power to decide upon a political question: when has political gerrymandering gone too far. In the absence of any “limited and precise standard” for evaluating partisan gerrymandering, federal courts cannot resolve such issues. (Roberts, 2019)

One might reasonably question the validity of the conservative justices’ claim that the Court is constrained on the issue of partisan gerrymandering by the lack of a “limited and precise standard”. The Supreme Court has a well-documented history of citing the 14th Amendment to prevent racial gerrymandering beyond the original language of the Voting Rights Act, while a “limited and precise standard” did not exist. It even produced a legal test for determining racial gerrymandering in Miller v. Johnson (1995).

Nevertheless, the legal reasoning behind the majority opinion presents several genuinely curious political questions. Why is it so hard for legislatures to set up a concrete legal standard or to find a workable solution to prevent gerrymandering? What is stopping the legislators from tackling an issue that is tantamount to electoral cheating? And since a large part of the reasoning behind the majority opinion is predicated on potential political solutions for partisan gerrymandering, what are the viable legislative options for stopping it in the United States?

This essay seeks to identify the prospect of such reforms, the obstacles along the way, and the potential strategies. It considers the gerrymander-polarization feedback loop as the core reason why gerrymandering is so hard to eradicate, and argues that the best way to combat gerrymandering is through independent districting. It is worth noting that the essay’s scope will be limited to Congressional redistricting.

Partisan Gerrymandering: How it works

To produce any prognosis, we first need first understand the status quo of a heavily gerrymandered America. Partisan gerrymandering means manipulating boundaries of electoral districts for the advantage of one political party by giving that party as many seats as possible. It is one of three kinds of gerrymandering. The other two are bipartisan gerrymandering, where districts are drawn to favour the incumbents by demarcating lines along the borders of party strongholds, and racial gerrymandering, which uses the racial makeup in local demographics to segregate voters. The former has been determined by the Supreme Court to be legally sound in Gaffney v. Cummings (1973), and the latter has been relatively less frequent in recent years. For the purposes of this essay, mainly partisan gerrymandering will be examined, even though racial gerrymandering often overlaps with partisan gerrymandering given the parties’ diverging performances in different ethnic groups.

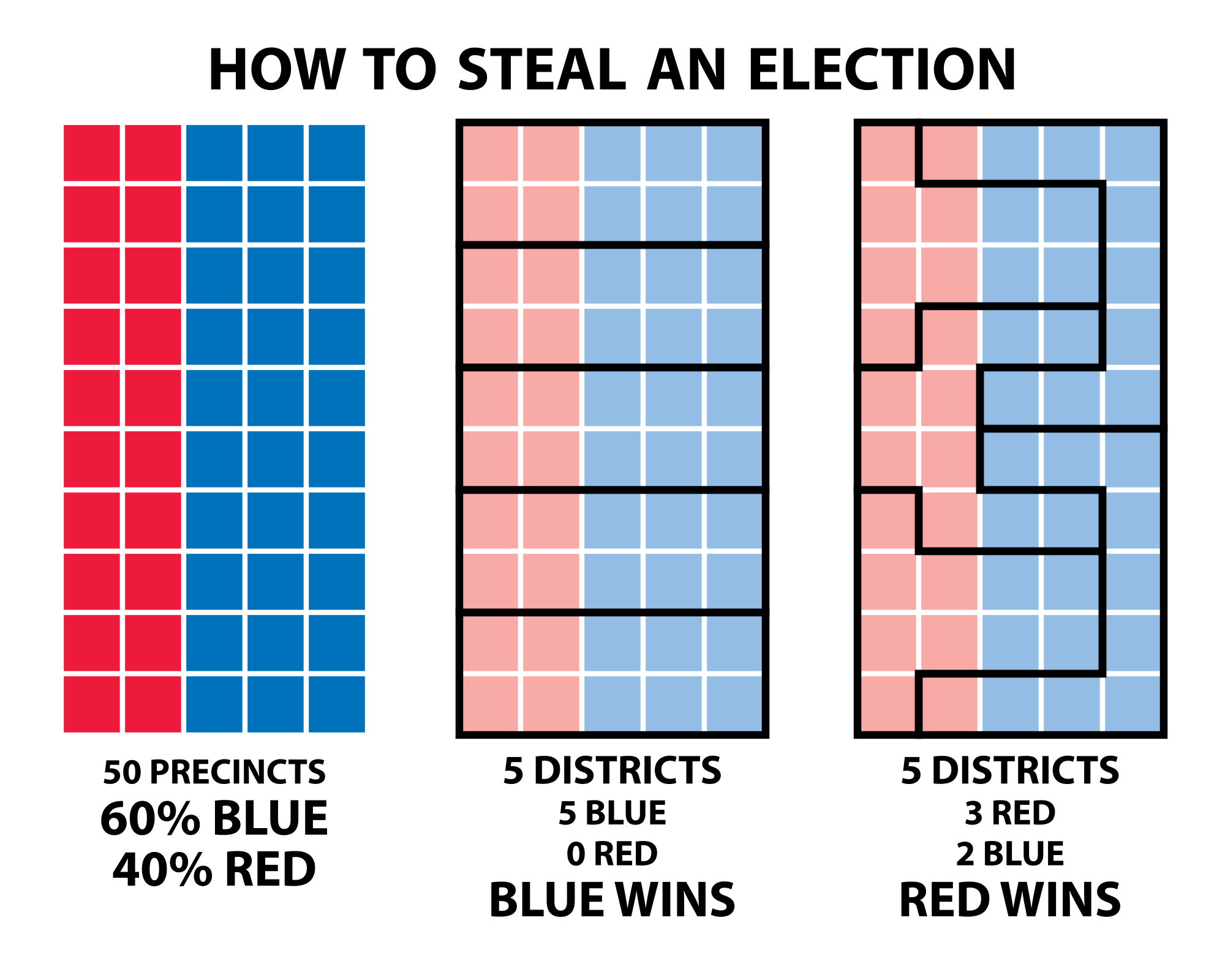

For a political party to secure the largest amount of seats with a given amount of voters through partisan gerrymandering, the district lines should be drawn in a way that most efficiently translates the votes into seats. Votes for a losing candidate and votes that go toward a surplus that a winning candidate does not need are all considered “wasted”. Partisan gerrymandering is to maximize these wasted votes for the other party while minimize one’s own. (Stephanopoulos & McGhee, 2015, p. 851-853) This is done in three ways, as described by Mann and Ornstein. The first one is “packing” as many opposition voters into as few districts as possible, giving one’s own party the largest amount of districts where it can secure a majority. The second one is “cracking”, in which the majority party spreads the opposing party’s supporters among multiple districts to dilute their influence. The third is “tacking”, which unnaturally extends a district beyond its normal boundaries into another distinct neighbourhood to include more desirable voters. (Mann & Orenstein, 2008)

Should the efforts prove successful, the playing field should no longer be level for both parties. An easy way to quantify this artificial partisan asymmetry is through the Efficiency Gap formula introduced by Stephanopoulos and McGhee, which is rather simple:

Efficiency Gap = Seat Margin – (2*Vote Margin)

“Seat Margin” is a party’s seat share minus 50%. “Vote Margin” is a party’s vote share minus 50%. The larger the Efficiency Gap, the more likely that an electoral map is gerrymandered on a partisan basis. (Stephanopoulos & McGhee, 2015, p. 853-854)

Their research, which was produced in 2015, analyzed electoral data of every congressional election from 1972 to 2012. They found a substantial amount of evidence of partisan gerrymandering either in favour of Democrats or Republicans, concluding that the Efficiency Gap has grown, over time, larger and more pro-Republican and spiked during the 2012 elections, suggesting an increasing impact of partisan gerrymander in general. Stephanopoulos & McGhee, 2015, p. 875-876)

While such data is helpful in identifying the problem, it is unclear how useful an analysis purely on a national level might help find the right political solutions, given the rules surrounding districting and redistricting make them mostly a state-level affair. Current rules of redistricting for Congressional maps fall largely into two categories: federal and state level. Constitutionally, Congress is the ultimate decisionmaker on how its elections are held, and Congress has made conscious choices to leave more room for the states. The Uniform Congressional District Act of 1967 requires that representatives be elected from single member districts. The Reapportionment Act of 1929 gives each state the right to set its own standards for drawing the maps for Congressional and legislative districts. In short, Congress has mandated that all states draw electoral maps, which is a process that Congress does not directly participate in. Therefore, the potential for gerrymandering largely falls into the prerogative of state legislatures. (Suess, 2016)

The State of Partisan Gerrymander

While it is a national problem, not all states have or are capable of having electoral maps drawn in a partisan fashion. Seven states do not have maps to draw because they have only a single representative in the United States House of Representatives for the entire state due to their small populations. In the remaining 43 states that require districting, 25 states’ legislatures are primarily responsible for their redistricting plan after each decennial census. In many of these cases, the plans need approval by the state governor. (NCSL, 2019) These are the states that are most likely to engage in explicit partisan gerrymandering and, subsequently, frequently take their political brawl to court, as exemplified by the plethora of Supreme Court cases from some of the most heavily gerrymandered states.

To reduce the role that legislative politics might play, twelve states (Alaska, Arizona, California, Colorado, Hawaii, Idaho, Missouri, Montana, New Jersey, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Washington) use congressional redistricting by an independent or bipartisan redistricting commission called primary commissions. Six states (Maine, New York, Rhode Island, Utah, Vermont, and Virginia) authorize advisory commissions to propose new electoral maps, but subject these maps to legislative approval. Five states (Connecticut, Illinois, Mississippi, Oklahoma and Texas) have Backup Commissions that draw the maps in case the ones designed by legislatures are invalidated by courts. Iowa is the only state with non-partisan legislative staff drafting the maps and put them up for a vote in the Iowa legislature. (NCSL, 2019)

Rucho v. Common Cause was a combined case that covered appeals from both Maryland and North Carolina, two of the country’s most gerrymandered states. The decision left in place North Carolina’s map, which favours the GOP, and Maryland’s which favours the Democrats. As discussed, gerrymandered elections usually produce seat distribution that is disproportional to the vote share. For instance, Democrats won 48% of the popular vote in North Carolina but only secure 3 out of 13 congressional seats in 2018 largely due to gerrymandering. (Bazelon, 2019)

The electoral effect is clear as day in these states. These individual cases indicate both the severity and the direction of advantage, depending on which way the map is gerrymandered. And since 2012, the cumulative effect of gerrymander around the country generates the corollary, generic national advantage that is unequivocally leaning one way. Amidst these developments, some of the actors and observers of politics have been lambasting partisan gerrymander on a number of grounds. For instance, Mann and Orenstein argue that partisan gerrymandering results in a lack of competitive elections, biases statewide results in favour of the party that controls the redistricting process, allows legislators to “lock-up” elected offices for their own interests, causes increasingly polarized legislatures with reduced incentives for bipartisanship, favours state legislators’ partisan preferences over the preferences of their constituents, and sows doubts in the legitimacy of the elections. (Mann & Orenstein, 2008)

Most academics agree on two effects caused by entrenched gerrymandering across the nation in this day and age: larger incumbency advantage and pro-Republican bias in electoral results. Congressional elections have already been historically low in competitiveness. This is especially true of the House of Representatives, where 99% of incumbents standing for re-election were successful in the 2002 and 2004 elections. Even in the swing to the Democrats in 2006, no individual Democrats were defeated and 89% of standing Republicans were re-elected. (The Centre for Responsive Politics, 2019) Party advantage on the national level is also obvious, with New York Times Upshot estimating before the 2018 Midterm Elections that the Democrats needed more than 6% more votes nationally than the Republicans to overcome Congressional gerrymandering and secure a majority in the House. (Adler & Stuart, 2019)

Potential Remedies

Before looking more closely at the adverse implications of gerrymandering, I would like to first introduce the options of recourse for consideration. Various political and legal remedies have already been used or proposed to diminish or prevent gerrymandering in the country. These remedies normally fall into three main categories, each ranked from the most moderate to the most extreme: neutral districting limits, third party redistricting and electoral reform.

Neutral districting limits are the rules and laws on both state and federal levels that do not inherently favour any party, which curtail the level of creativity when designing a gerrymandered map. The federal government and states already have rules, laws, legal precedents or even constitutional provisions to refer to, ensuring basic protection for electoral integrity.

The most common forms of neutral districting limits are equal population, compactness, and contiguity. Equal population is an established federal legal principle that mandates each electoral district to contain virtually identically-sized populations. It was first introduced in 1962, when the Supreme Court decided Baker v. Carr (1962), also known as the landmark “one person, one vote” decision. In Baker, the Supreme Court, for the first time, held that an apportionment case can be justiciable based on the Equal Protection clause of the 14th Amendment, so it also opened the door for more subsequent court decisions involving all manners of gerrymander. Karcher v. Daggett (1983) further consolidated the “one person one vote” doctrine and held that population inequality between districts is not allowed unless the deviation can be reasonably justified in the name of public interest. (NCSL, 2019)

Compactness and contiguity rules are usually implemented on the state level, requiring that shapes of electoral districts are drawn in an outrageous way. These rules provide a baseline of defence against electoral map manipulation by subjecting the maps that violate these principles to judicial review. (NCSL, 2019) Apart from these, other civil rights legislations and constitutional provisions are also interpreted in a way that limits gerrymandering. The 5th, 14th, 15thAmendment and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 essentially ban racial gerrymandering in principle. (Bazelon, 2019)To be clear, these were not to ban districts that encompass majority-minority neighbourhoods. Rather, in Miller v. Johnson(1995), a map is only considered racially gerrymandered if race has been the predominant factor that determines the lines over districting conventions like the shared communities and previously mentioned compactness and congruity. Should a jurisdiction’s redistricting plan violate any of these aforementioned restrictions, federal and state courts have the right to order the jurisdiction to propose a new redistricting plan that remedies the gerrymandering.

Third-party redistricting has been adopted by 18 states in one form or another. The usual way to approach this is by setting up a redistricting commission or committee to draw the electoral districts, rather than to have the state legislatures do the drawing. Generally speaking, the idea is to create a nonpartisan or bipartisan body to circumvent the apparent conflicts of interest of having party officials determining the boundaries of their own districts. These commissions have had dramatic performance discrepancies across different states, with states like Arizona and Pennsylvania having the least gerrymandered maps in the country, to California where gerrymandering remains. (Wines, 2019) However, most of these commissions, similar to many other regulatory commissions, are still filled by political actors through appointment, making the composition of the membership an issue of political contention. Should that be the case, a third party commission designed to reduce partisan influence may succumb to political pressure. One such independent commission under intense political scrutiny is the one in Arizona, one of the least gerrymandered states in the country. The commission has been the target of attack from Republican lawmakers from the start. (Vasilogambros, 2019)

Electoral reform is about replacing the single member plurality system, also known as the first-past-the-post system, with alternative electoral systems. Instead of having one district produce one Representative, alternative systems produce winners in a way that would reduce the impact of redistricting or bypass the issue altogether. Some of these alternatives involve multimember districts that will combine several smaller existing districts into larger and fewer districts, while others will observe at-large elections that simply get rid of districting entirely, thus mitigate the impact and limit the potential for gerrymanders. Examples of systems that adopt multi-member districts include the single-transferable vote, cumulative voting, and limited voting. Proportional voting systems would bypass the problem altogether. In these systems, no districts are present, and the party that gets seats in the legislature proportional to their share of the popular vote. One caveat is that states will not be able to change the congressional electoral system in the states unilaterally as it requires federal legislation to modify the Uniform Congressional District Act (1967). As the law currently stands, no alternative to single member plurality is legal.

Out of the three, third party districting is perhaps the most practical one. Neutral districting limits are not the most effective at preventing partisan gerrymandering because of almost inevitable legislative ambiguity, leaving room for individual interpretation. And electoral reforms risk changing the cornerstone of the entire representative democratic system in the House of Representatives by disconnecting Representatives from local constituencies. Voters will not be thrilled by the idea of losing local representation and the surmised political headwind on electoral reforms will most likely be immense. That leaves third-party districting, a method that has already produced success in eradicating gerrymandered maps in sporadic corners of the country, the best option forward. But just as explained above, its adoption and implementation nationwide are obstructed by several obstacles.

The Polarization-Gerrymander Feedback Loop

Does partisan gerrymandering cause polarization?

Enacting any form of legislation setting up a non-partisan or bipartisan districting commission is the most intimately impactful issue that a legislator can face, since their jobs and political influence are often on the line. That kind of legislative effort requires both parties to act in good faith to deliver elections that are fair and appropriately reflective of the will of the electorate. Unfortunately, in a climate of political polarization that, I would argue, has been exacerbated by partisan gerrymandering, the conditions are gravely insufficient for a change like this.

For an example of the toxicity surrounding this possible reform, look no further than the state of Maryland, one of the most gerrymandered states in the country and one that heavily leans Democratic. On May 8, 2017, Governor Larry Hogan, a Republican, vetoed a bill passed by the Maryland General Assembly that would change Maryland’s redistricting process to a non-partisan one. The bill envisioned an independent redistricting panel, similar to the redistricting commissions in other states, that would demarcate the boundaries for congressional and state legislative districts in Maryland. However, the legislation was proposed as an interstate pact that would only go into effect if the same bill passed in five other states, including New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Virginia and North Carolina. Two months prior to this bill, Hogan supported another proposed legislation establishing a nonpartisan redistricting commission in Maryland unilaterally without having to wait for other states. But the legislation failed in the Assembly, largely due to Democrats’ opposition. (Broadwater, 2017)

How did two similar proposals for independent redistricting from both parties fail? While they dwelled over the issue of an interstate pact, I find the post-veto rhetoric from both parties most illuminating. Governor Hogan, the Republican, said, “Instead of choosing fairness and real nonpartisan reform, [the Assembly] pushed through a phony bill masquerading as redistricting reform. It was nothing more than a political ploy designed with one purpose in mind: To ensure that real redistricting reform would never actually happen in Maryland.” Senate President Thomas Mike Miller (D) and House Speaker Michael Busch, both Democrats, responded to Hogan’s veto by saying, “Today’s veto reveals that, instead of supporting a true, nonpartisan solution that could restore accountability and cooperation to Washington, Governor Hogan prefers his plan to simply elect more Republicans to Congress.” (Broadwater, 2o17)

Both accusing the other party of acting in bad faith, yet both parties were publicly committed to the idea of independent redistricting. The breakdown of trust signals that political polarization is deterring legislative progress for change. This is a prime example of how polarization and gerrymandering interact. They form a vicious circle.

There is abundant political science research into the correlation between polarization and gerrymander. The conclusions have varied from no correlation to a strong correlation. One prominent study by Abramowitz, Alexander, and Gunning in 2006 tested three variables against one another: redistricting, partisan polarization, and incumbency. They found little evidence suggesting a major impact from redistricting. (Abramowitz, et al. , 2006)

McCarty, Poole, and Rosenthal also rejected the impact of gerrymandering on political polarization. However, they did find that, consistent with the Stephanopoulos and McGhee research, redistricting gave Republicans a national advantage and redistricting negatively affected competition. (McCarty, et al., 2009, p. 678-679)

There are two potential causes for the lack of a clear correlation between gerrymander and polarization in these researches. One is that bipartisan gerrymandering has the potential to cancel out some of the partisan gerrymandering’s effect since they go in different directions. Incumbency security is often sacrificed for maximum party gains. If the majority party in a state tried to maximize the number of seats it wins in future elections, it would attempt to create as many districts where it can command a majority of voters as possible. Doing so means opposition voters are fitted into as few districts as possible. This process pits electoral security for the individual members of the majority party against the party’s overall performance in the seat count. Consequently, the two competing interests in gerrymandering may not cause as much of a drop in competitiveness as we would expect.

The second cause is that the analyses were done on a national level. A number of other researches have explained the apparent correlation between political polarization and uncompetitive elections without including gerrymander by attributing them to the states’ realignment along political lines, to the sorting effect in which Democrats become less likely to represent conservative districts and Republicans become less likely to represent liberal districts, and to the winner surplus effect of first-past-the-post. The role of gerrymander can be easily diluted by all these other variables on a national scale, given the varying degrees and different circumstances in each state. Furthermore, the exploration between gerrymander and polarization on a national scale is rather useless for the purposes of explaining why it is so hard for the states to stop gerrymandering. What we need is whether polarization grows locally when local districts are gerrymandered.

The findings are very different once we move down from a national analysis to local analysis that focuses on the internal dynamics of the constituency and states, particularly the ones that have severely gerrymandered map. Carson, Crespin, Finocchiaro, and Rohde, found that even tested against the overall trend of increasing polarization, “districts that have undergone significant changes as a result of redistricting have become even more polarized.” And that kind of localized polarization encapsulate the congressional representative, the voters, and the local officials, all of whom are instrumental in producing or stopping gerrymander. (Carson, et al., 2007, p. 897-899) Mann and Ornstein argued that while other factors may be more statistically obvious polarization,

“…redistricting makes a difficult situation considerably worse. Lawmakers have become more insular and more attentive to their ideological bases as their districts have become more partisan and homogeneous. Districts have become more like echo chambers, reinforcing members’ ideological predispositions with fewer dissenting voices back home or fewer disparate groups of constituents to consider in representation. The impact shows in their behaviour.” (Mann & Ornstein, 2006)

Separate research into independent districting commissions has also shown that “politically independent redistricting seems to reduce partisanship in the voting behaviour of congressional delegations from affected states in statistically significant ways.” (Oedel et al., 2009, p. 87)

Gerrymandering of Congressional maps is always in concurrence with the gerrymandering of local legislative election maps. There is virtually no research on how gerrymandering may cause polarization in state legislatures. But along the logic of these researches on Congressional polarization, and since the research of Carson, Crespin, Finocchiaro, and Rohdemore have proved that local constituencies and Representatives are more polarized than average when their maps have been heavily gerrymandered, focused gerrymandering in a smaller, more contained environment of a state where third-party redistricting does not exist should have a more polarizing effect on state legislatures than it had on Congress, not less.

Does polarization hinder efforts to curtail partisan gerrymandering?

Once again, there is virtually no research that specifically studies what political conditions may or may not help reach a solution towards ending gerrymandering. Therefore, I will try to present a few causal mechanisms that may explain how polarization may be the obstacle undermining anti-gerrymander measures like third party districting, or may even encourage political actors to further exploit the benefits of partisan gerrymandering.

First, Congressional and local polarization marginalize bipartisanship, a major element in getting legislations passed. Harbridge found that bipartisanship in Congress had been in statistical decline from 1973-2004 in every way, from bipartisan roll call votes, to bipartisan cosponsored bills to the influence of bipartisan cosponsor coalitions within either chamber of the Congress. (Harbridge, 2015, p.18-25) Losing legislative allies to ideological polarization means that to push through any legislative agenda, party leaders must then rely more heavily on party unity than collaborators from across the aisle. This shifting strategy further incentivize party gerrymandering to get as many seats as possible with a given voter base, to overcome the majority or outvote the minority.

To achieve that in a system where redistricting is handled on the state level, federal party organizers have to coordinate their operations to shore up their control of state governments and legislatures as well. It has been revealed that this is the strategy adopted by the 2010 Republican National Committee Redistricting Majority Project, or REDMAP, which is a $30 million dollar strategy to help state Republicans capture state legislatures that would be drawing the Congressional districts that federal Republicans wished to capture before the decennial census. In one of the 70,000 documents retrieved from the hard drives of the late Thomas Hoefeller, a Republican strategist and lawyer who specialized in redistricting, GOP strategists boldly claimed that in 2011 the “energy and resources poured into last year’s legislative races are paying large dividends in the ongoing redistricting process,” and that “the tide of victory” helps “increase our control” over new maps. (Daley, 2019)

Second, the polarization of the electorate manifests itself in a way that is increasingly convenient for mapmakers to gerrymander the electoral maps more effectively. The sorting effect, where fewer Democrats represent conservative districts and fewer Republicans represent liberal districts than ever before, was recognized in McCarty, Poole, and Rosenthal’s research as a sign of voters consolidating their party preferences. (McCarty, et al., 2009, p. 667) Persuadable voters, therefore, are increasingly rare. Polarization is also manifested through a rural-urban divide that Emily Badger of the New York Times calls “America’s Political Fault Line”. (Badger, 2019) The consolidation of political preferences within urban and rural communities, coupled with the sorting effect, is naturally drawing clear partisan boundaries for mapmakers to refer to when they start modifying them to their liking.

Political Historian Julian Zelizer (2016) wrote an editorial for the Washington Post on REDMAP in 2016. He specifically alluded to the amount of demographic information on political leaning that the program had access to, and how they used sophisticated mapping software such as Maptitude to geofence favourable conservative white voters into their preferred districts.

Third, like previous discussed, for third-party, independent redistricting to work, both political parties need to reach a consensus in good faith to make districting a public administration issue rather than one about partisan politics. But as mutual trust breaks down in a polarized environment where the minority party feels wronged by a gerrymandered map and the majority party fears retribution, neither party can be sure that the other one is acting in good faith. Consequently, an independent districting commission will still be a point of political contention, especially on the issue of appointments.

For this, we look to Canada. Canada is also a country that uses first past the post system to elect its legislators. But in recent decades, gerrymandering has become an anachronistic political activity that simply does not exist anymore. When the Canadian electoral maps need to be redrawn, ten independent electoral boundaries commissions – one in each province – are established to revise the electoral district boundaries in their respective provinces. Each commission is composed of three members. It is chaired by a judge appointed by the chief justice of the province and has two other members appointed by the Speaker of the House of Commons. (Elections Canada, 2019)

Both of the provincial Chief Justices and the Speaker of the House, along with the Electoral Officers of each province, are required by law and conventions to be strictly impartial and forbidden from participating in partisan activities of any kind. Their American counterparts are not restricted in the same manner. State judges are elected in most states, and 18 states even hold elections in which the judicial candidates run with explicit party affiliations. Speakers of Legislatures are meant to be the highest-ranking official of the majority party rather than an impartial authority presiding over the parliamentary business. And state Secretaries of State, often the state official in charge of overseeing the elections, are themselves elected in partisan races. Without comparably impartial officials, it is unclear what kind of appointment solution would sufficiently assure both the majority and minority parties.

Conclusion

Partisan gerrymandering is rightfully bemoaned for how insidious it is. It diminishes confidence in the electoral system and representative democracy. It reduces competition in elections and, by extension, the competition of ideas. It boosts polarization in a country where gridlock is already the status quo. It is inherently unfair and unethical. Looking through the options, third-party, independent districting is the most effective solution for this phenomenon bedevilling American politics, if voters in the country still want to keep their electoral districts instead of swapping them for another electoral system. Lastly, to implement such a change would be no easy feat when gerrymander and polarization seem to work in synergy.

The last remaining question is what kind of strategy is the most effective in instituting such a change. The key to success is to break the feedback loop between gerrymander and polarization, and to stop this trend of power begetting power. Rucho v. Common Cause has fully exposed the weaknesses in a strategy that places too much hope on judicial recourse, as the courts seem to operate along the same partisan lines as the ones everywhere else. I have no silver bullet, but one method has proven more straightforward than most: state ballot measures. This method has been proven especially useful after Arizona voters adopted Proposition 106 in 2000 to establish their independent redistricting commission. Similar ballot measures have already passed in Michigan, Utah and Missouri in 2018, and are pending in Arkansas and Oklahoma. (NCSL, 2019) A citizen initiative immediately bypasses the much-lamented apparent conflict of interest of legislatures, and force the measure through a vote by the electorate that is, by all accounts, more moderate than the political elites.

Works Cited

Chung, Andrew; Hurley, Lawrence. “In major elections ruling, U.S. Supreme Court allows partisan map drawing”. Reuters. June 27, 2019.

Rucho v. Common Cause, No. 18-422, 588 U.S. (2019).

Miller v. Johnson – 515 U.S. 900 (1995)

Gaffney v. Cummings, 412 U.S. 735 (1973)

Stephanopoulos, Nicholas O., and Eric M. McGhee. “Partisan gerrymandering and the efficiency gap.” U. chi. l. Rev. 82 (2015): 831.

Mann, Thomas E., and Norman J. Ornstein. The broken branch: How Congress is failing America and how to get it back on track. Oxford University Press, 2006.

Uniform Congressional District Act H.R. 2508 (90TH Congress)

Kennedy, Shella Suess. “Electoral Integrity: How Gerrymandering Matters” Public Integrity. Volume 19, 2017 -Issue 3. 2016. Online.

Bazelon, Emily .”The New Front in the Gerrymandering Wars: Democracy vs. Math”. The New York Times. 2019

“Redistricting Commissions: State Legislative Plans” ncsl.org. National Conference of State Legislatures. Apr. 18, 2019.

“Reelection Rates over the Years” OpenSecrets.org. The Centre for Responsive Politics. Retrieved on Dec. 13, 2019

Adler, William T., Thompson, Stuart A. “The ‘Blue Wave’ Wasn’t Enough to Overcome Republican Gerrymanders” The New York Times. Retrieved on Dec.13, 2019.

“Redistrciting Criteria”. ncsl.org. National Conference of State Legislatures. Apr. 23, 2019.

Wines, Michael. “What Is Gerrymandering? And Why Did the Supreme Court Rule on It?” The New York Times. June 27, 2019.

Vasilogambros, Matt. “The Tumultuous Life of an Independent Redistricting Commissioner” Pew Charitable Trusts. Nov. 26, 2019.

Broadwater, Luke. “Hogan vetoes redistricting bill, calling Maryland Democrats’ measure ‘phony’”. The Baltimore Sun. May 08, 2017

Abramowitz, Alan I., Brad Alexander, and Matthew Gunning. “Incumbency, redistricting, and the decline of competition in US House elections.” The Journal of politics 68.1 (2006): 75-88.

McCarty, Nolan, Keith T. Poole, and Howard Rosenthal. “Does gerrymandering cause polarization?.” American Journal of Political Science 53.3 (2009): 666-680.

Carson, Jamie L., et al. “Redistricting and party polarization in the US House of Representatives.” American Politics Research 35.6 (2007): 878-904.

Harbridge, Laurel. Is Bipartisanship Dead?: Policy Agreement and Agenda-Setting in the House of Representatives. Cambridge University Press, 2015.

Daley, David. “‘WORTH THIS INVESTMENT’: MEMOS REVEAL THE SCOPE AND RACIAL ANIMUS OF GOP GERRYMANDERING AMBITIONS” The Intercept. September 27, 2019.

Badger, Emily. “How the Rural-Urban Divide Became America’s Political Fault Line” The New York Times. May 21, 2019.

Zelizer, Jualian E.. “The power that gerrymandering has brought Republicans”. The Washington Post. June 17, 2016

“The Role of the Electoral Boundaries Commissions in the Federal Redistribution Process” Elections Canada. Retrieved on Dec. 13, 2019.