Hi there! Welcome to our second blog post!! Please follow us and see & hear our awesome journey with the Indigenous Foodscapes Project~~~

Check this out -> Here is the finalized Group Proposal PDF our brillant team came up with G19-Proposal (link).

Weekly Objectives:

| Weekly Objectives | Achievements |

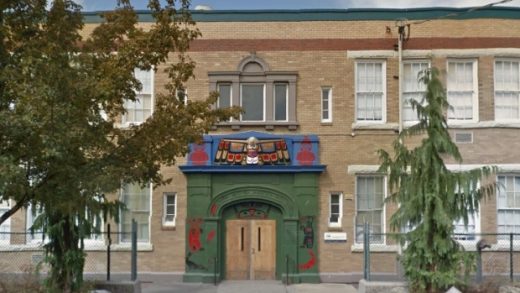

| Week 3 & 4: School Visits & Recording Information | We completed our first objective from Feb. 1st to Feb. 23rd. We did this by visiting Xpey and Queen Mary Elementary Schools on Feb.1st and Feb. 9th, 2018. At each school, we took photos of the garden plots and plants, audio recordings of conversations between Lori and the school teachers, and written notes, all in accordance with ethical and consent guidelines. After the school tours, we transcribed our audio files and added maps to our notes to show the locations of the food assets: gardens, current plants, plants Lori suggested that the schools could use, and other required materials (eg: mulch) if needed.

|

| Week 6 – 8: Compile Information (photos, audio, notes) & Prepare for the draft report |

We are currently working on our second objective, which is to compile a multimedia report that will be shared with funders, schools, and the public. For our project, the multimedia report will be presented as an interactive website. We are actively organizing audio, pictures, and information from our notes to create a sample of what our interactive website would look like which will be presented at the Vancouver School Board on March 5th. As such, we have split up the work by the team members who went on either school tour, and are in constant communication to keep up with the deadlines we set for each task! |

The Colonizer and the Colonized

“To decolonize food justice scholarship, we must welcome, humbly, and perhaps even embarrassingly, age-old yet alternative methods of sharing knowledge” (Bradley et al., 2016).

Farm-to-School Indigenous Foodscapes is a collaborative project between local first nations, the Vancouver School Board and Students from the Land and Foodsystems program at UBC. Each of us represents a different aspect of colonial history in the form of the once colonized and once colonizer: first nations, government, and academia. The goal of our collaboration is to impact the minds and hearts of students in regards to food, medicine, the environment and our indigenous cultural history through an interactive foodscape program that broadly facilitates decolonization. However, within any sort of socially reformative collaboration, change doesn’t occur as a means to an end but rather as a means in itself. In other words, in order for change to occur outside a closed group, the group itself must first become self-aware (Bradley et al., 2016). Such self-critique can be awkward and uncomfortable, however, it is necessary in order for any sort of social reform to be long-lasting and meaningful. In addition to being self-critiquing, reconciliation also requires us to be open to listening and empathizing with those around us. Despite noble intentions, colonial mindsets can and do still permeate many minds, particularly academic minds. Similarly, colonized mindsets can also still permeate the minds of those once colonized or socially oppressed. Reconciliation requires both the colonizer and the colonized to deconstruct their fabricated mindsets in order to more humbly, accurately and intentionally communicate. During one of our school tours we had a subtle, yet interesting divergence of worldviews from the perspective of academic vs indigenous ways of “knowing” and teaching. Here, Lori came to the rescue and helped bridge the gap between the colonizer and the colonized. Trust and forgiveness then became the foundation for the rest of our meeting. It is here, with self-critique, openness, empathy, forgiveness, and trust that inter-group mindset reformations spawn and spread to out-of-group social reformations. This is the aim of reconciliation.

“The process of decolonization requires us to embrace what we don’t already know or understand” (Bradley et al., 2016).

In addition to the principles of reconciliation, we also learned about indigenous principles on our walking tour. Our interpretation of such principles were: Reverence for the natural world, Collaboration between plants and people and people and plants, and Regeneration of natural (here food) resources.

What, so what, now what?

What (was good about the experience)?

Collaboration:

One of the most vital parts of this experience was going on the school tour and getting the chance to hear Lori share her knowledge with all of us. It has opened our eyes to see how school gardens can impact a classroom and be an invaluable tool for bringing people and plants together regardless of their indigenous ancestry.

Reverence for the natural world:

During our tour, Lori introduced us to the concept that there is beauty in the smallest of plants that seem insignificant at first glance. This reverence for the natural world has allowed us to appreciate this knowledge for ourselves but also to recognize the potential for incorporating Indigenous Foodscapes into a dynamic student curriculum that transfers this same reverence into the hearts, minds, and bodies of students. “We need to be in gratitude to this incredible world we are living in”.

So what?

Sometimes the appreciation for the assets we have in our gardens needs to be learned. There are times where a sense of childlike awe comes naturally when we see something beautiful, and other times when hidden treasures need to be pointed out to us. We felt this when Lori would point out little nooks and crannies on the schoolyard that seemed to be forgotten or neglected. “Who are you? Can I eat you? Can I make a medicine? …Everything has a purpose”.

The academy encourages particular ways of presenting ideas, for example discouraging the use of the first person (Bradley et al.,2016). Contrastingly, personifying plants, as Lori did here adds an extra layer of appreciation for them which may otherwise be lost in traditional, colonial academic institutions. This is just one example of what “indigenizing a food system” could mean.

A sense of gratitude for the environment that surrounds us is an invaluable asset that the next generation needs so they can develop a sense of social and environmental responsibility in order to collaboratively regenerate the world around them and help fix an unsustainable food system. Several areas in need of regeneration in our current colonial food system were pointed out to us during our walking tour:

1. Fast Food (degeneration): “It’s not always about bigger and better”

2. In indigenous food systems, seeds used to be commerce (regeneration): “How do you think they (first nations) survived [before colonization]?”

3. Seed propagation.. perhaps some Gorilla gardening?: “This was our responsibility (plant propagation)…we [were] the legs to the plant world.”

Now what?

We are currently working on compiling all the information we have gathered from the tour in a way that is organized and efficient to reference. This is inclusive of selecting pictures to feature and transcribing audio clips. We are also in communication with teachers who were on the tour in order to exchange ideas and notes. Many of the teachers we met had a lot of energy and shared the same passion and excitement that Lori displayed. We are working towards creating a plan that will allow them to maximize each school’s current assets and hopefully inspire their pedagogies.

Since the broader goal of the Farm-to-School Indigenous Foodscapes program is to help facilitate the decolonization of our current food system, it becomes imperative that we relearn Indigenous ways of interacting with food. During our tours, we learned three indigenous principals: appreciative inquiry (reverence), collaboration (people-people and plant-people interactions), and the regeneration of resources (people acting as vectors for plant propagation/ knowledge). We also learned principles of reconciliation: self-critique, openness, forgiveness, and trust.

| Upcoming Objectives | Strategies |

Week 9 – Draft Report Presentation @VSB (Vancouver School Board)

|

|

| Week 10 – Infographic & Interactive website Making |

|

Week 11 & 12 – Final Presentation

|

|

| Week 13 – Final Report |

|

So far, we have a good time working together as a team and we have learned a lot of Indigenous plants with Lori. We are excited about presenting our knowledge in the next few weeks! Follow us and read our next blog as we continue on our journey!

References:

Bradley, K., & Herrera, H. (2016). Decolonizing Food Justice: Naming, Resisting, and Researching Colonizing Forces in the Movement. Antipode, 48(1), 97–114.