The existence of the different entry points affords co-construction of the knowledge between reader and writer. The convention of the traditional page’s one entry point (Kress 2005) channels the reader to the writer’s single pre-packaged interpretation. However, Kress goes on to state that technology had opened the construction and structure of books. For example, SocialBooks (Douglas, 2015) images, interactive stories, and marginalia open the reading process.

However, bringing texts to life requires more than thinking about content. It requires inventive ideas about creating and design and keeping up with the affordance of digital hardware and software.

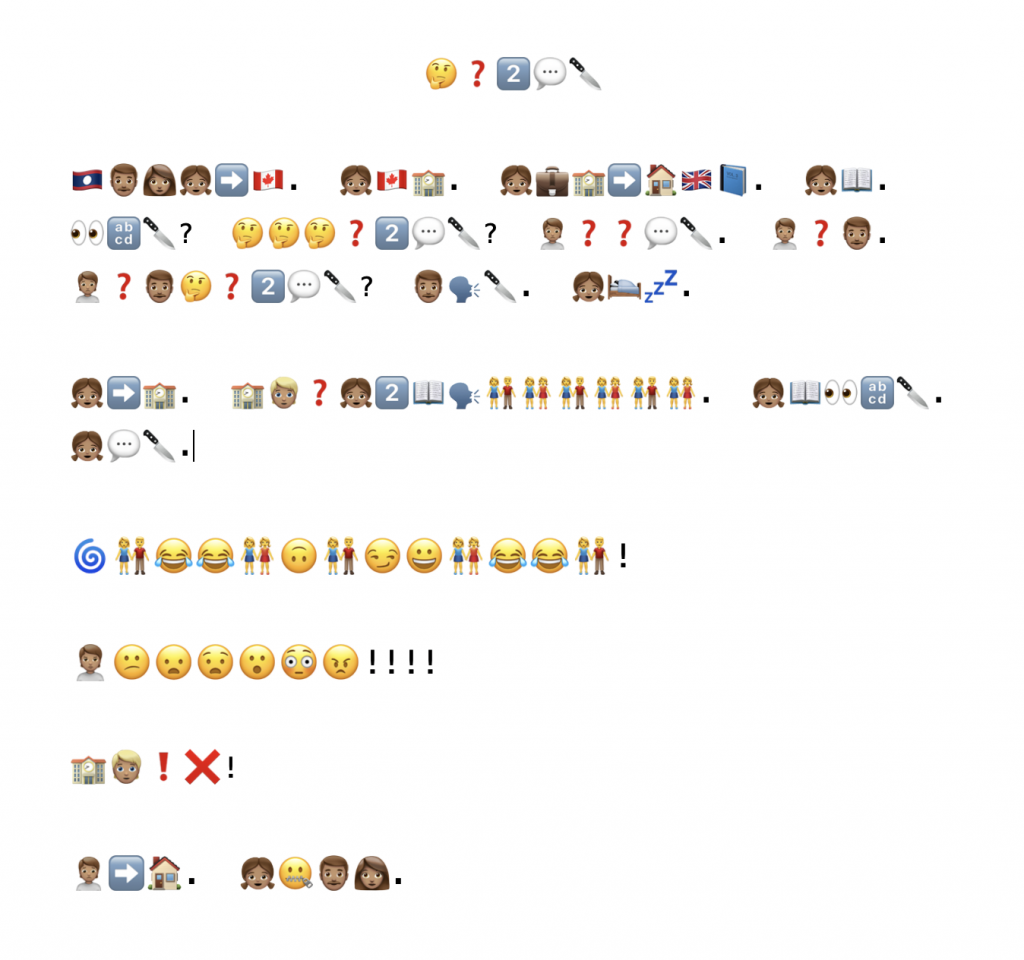

I started to translate a recently read book and its plot into the emojis code. I choose to attempt this unknown code without assistance, even though https://emojitranslate.com/ exists and ended up with three versions.

version iii

social reading in chat medium

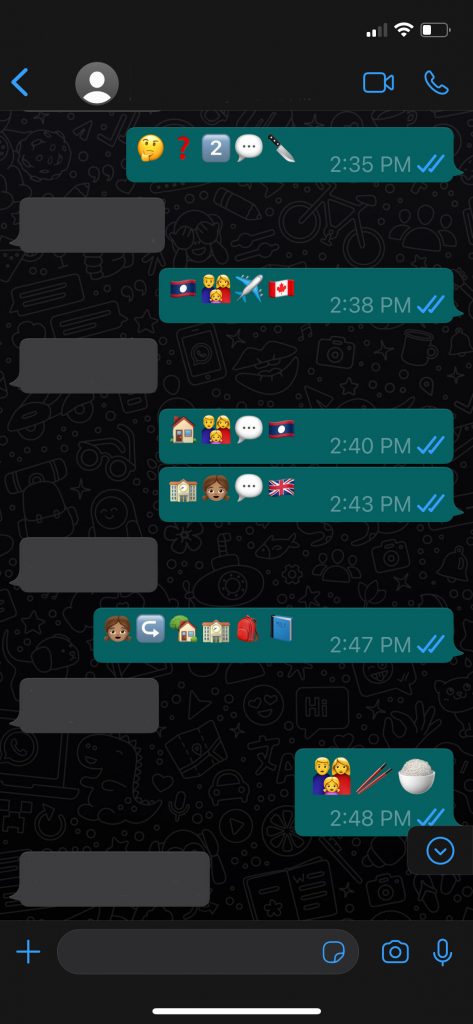

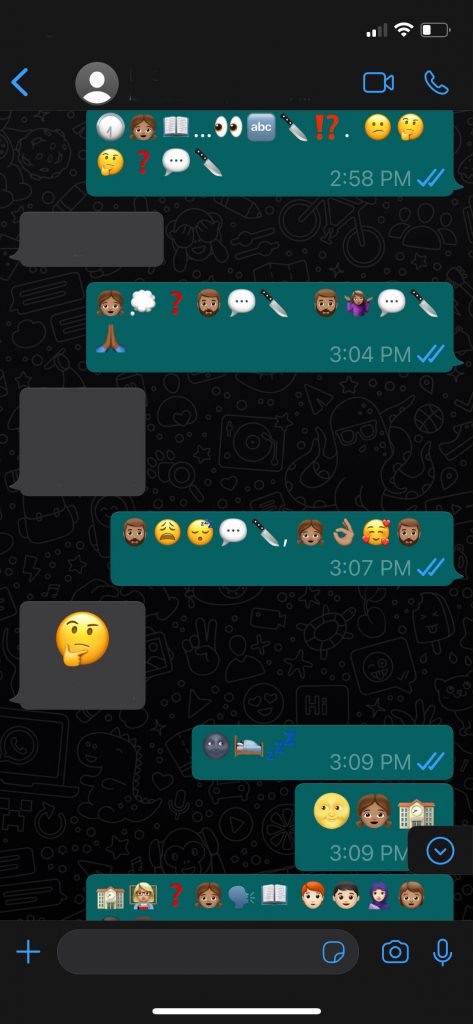

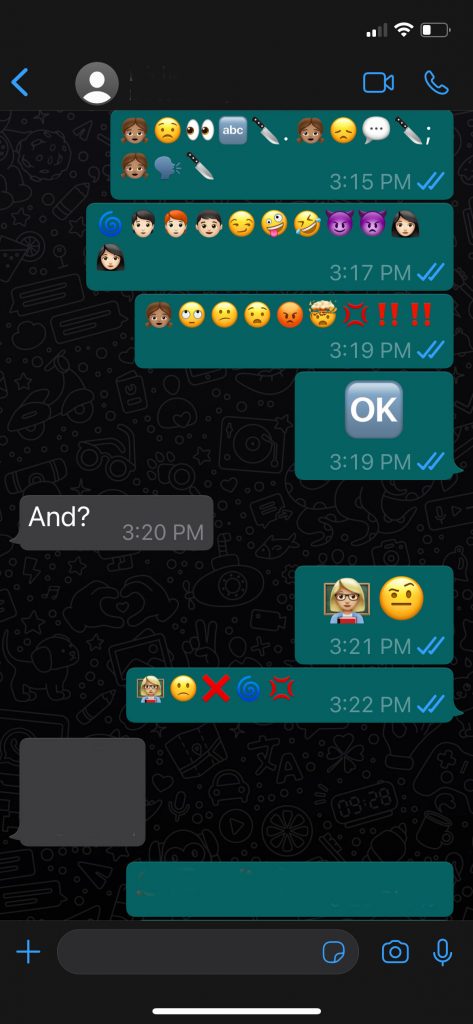

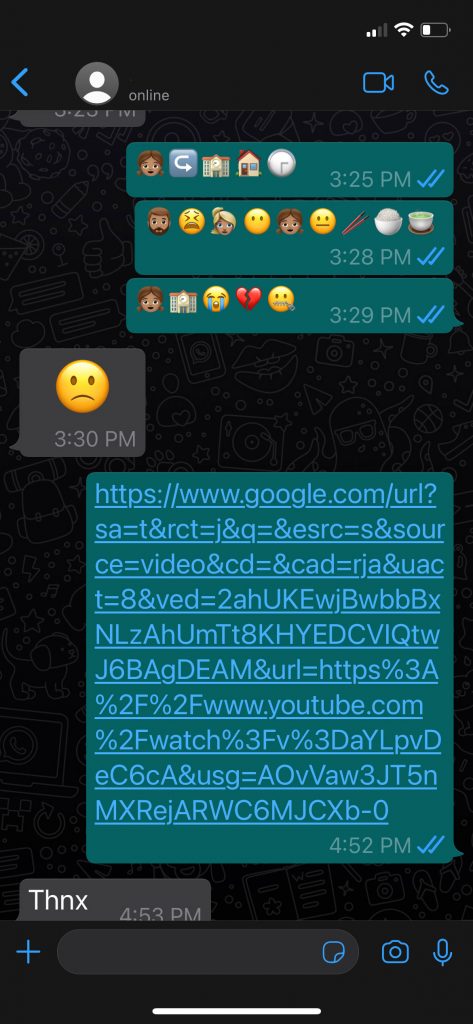

The problem of how to punctuate the iconic text brought forth the question: Why am I creating the emojis story with word processor programs and not a messaging app? Thus, the third version examines the task from WhatsApp, a cultural space of memes, gifs, and emojis. Texting works as an expansion of speech. The text utterance combines heterogeneity of form and content (Bolter, 2001). Text, emojis, images, links (video, audio and webs) are cobbled together in a phrase. Therefore, the writer is not thinking in terms of independent and dependent clauses when the thought is complete. The ideas are located in a speech bubble. Finally, the sender hits send, breaking the utterance into thinking streams without the need for punctuation.

Internet speak has freed itself of the idea of the canonical text (Scholes, 1992), where participants can play by layering tone and expressions on the literal words. However, the emojis have a subtle relationship with each other (McGulloch, 2019), so while the third version may have a better look, the emojis manipulation would not be considered authentic by the millennials in this shared space.

version ii

iconic code via static writing program

The second version applied my knowledge as a second language instructor. Translations require fluency in both codes. While I have fluency in English, my emojis literacy would be pre-productive. I am not unaware of its existence; yet, my daily written digital verbalization (formally and informally) on a networked screen rarely comprises emojis. The Institute of the Future of Book (n.d.) might attribute this to my working in an academic institute created in the age of print that informs the structure and rhythm of my work. In other words, my preference for words is ‘old school.’

Therefore to reduce the high cognitive demand involved in producing an intelligible text, I resorted to the English labels of each emoji from https://emojikeyboard.io. I also loosened the English syntactic arrangement, not always read left to right with an agent doing an action. I also tried to incorporate emojis to capture the story’s point about a child’s trust and awe in a parent out of step with society, leading to shame. But, unfortunately, I still thought about the static paper medium with the mode of writing. As I still set out the story in sequential order. However, the medium of the screen and the image mode changes semiotic (Kress, 2005). So I stumbled trying to get the icons to narrate the story even though images display information. Kress (2005) claims that “The logic of space works differently: In the message entity (the image), all elements are simultaneously present …and so it is the viewers’ action that orders the simultaneously present elements concerning” the framing of the space (p. 16). So I decided to try a third version.

version i

translation: alphabet to iconic code

“Writing …is a particularly pre-emptive an imperialist activity that tends to assimilate other things to itself” (Ong, 2002, p. 11). Thus, the first version was grounded in written English. I translated the English Roman alphabetic code into the iconic code. I merely swapped the English words for icons that best represented the label. The syntax remained English. The result of framing was a basic simple agent action object pattern in an independent clause-like structure. I punctuated to indicate the end of the thought and paragraphed for the same reason: one idea per sentence and one thought per paragraph. Making more elaborate structures was difficult as the icons represented content and not function words that hold complex sentence structures together.

The book chosen was the last I read for pleasure. I asked myself the salient events and temporal order (Kress, 2004) and attempted to hold to it. Moreover, by adding to this strategy, the substituting of the code resulted in clumsy, stiff unintelligible thought patterns that had a minuscule likelihood of not being discernible to an audience. Furthermore, it in no way captured the gist of the author’s point for the short story. Thus I thought it would be good to treat emojis like a legitimate written code and reattempt the venture.

concluding thoughts

How will technology impact books? As technology changes, so will the affordance available to the book, as technology has always been implicated in writing (Haas, 1996). As a result, icons, marginalia, and images, part of medieval manuscripts, have resurfaced. In addition, there will be other features that will be incorporated into the future electronic book, such as social reading. However, words and physical book will still have their place in our lives.

references

Bolter, J. D. (2001). Chapter 4:The breakout of visuals. In Writing space: Computers, hypertext, and the remediation of print (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Douglas, C. (2015, September 15). SocialBook: The coolest reading tool you’ve never hear od. If:Book Blog. https://chadtdouglas.wordpress.com/2015/09/15/socialbook-the-coolest-reading-tool-youve-never-heard-of

Haas, C. (1996). Writing technology: Studies on the Materiality of Literacy (1st ed.). Routledge. In

Kress, G. (2005). Gaines and losses: New forms of texts, knowledge, and learning. Computer and Composition, 2(1), 5–22. https://doi.org/doi:10.1016/j.compcom.2004.12.004

McCulloch, G. (2020, November 29). Because Internet (No. 194). https://omny.fm/shows/you-are-not-so-smart/194-because-internet

Ong, W. J. (2002). Chapter one: The Orality of language. In Orality and literacy: The technologizing of the word (pp. 1–11). Routledge.

Scholes, R. (1992). Canonicity and Textuality. In Introduction to Scholarship in Modern Language and Literatures (2nd ed., pp. 138–158). Modern Languages Association of America.

The Institute for the Future of the Book. http://www.futureofthebook.org/

Zaltsman, H. (2019). 102. New Rules (No. 102). http://theallusionist.org/new-rules

I love your idea to make use of the texting format to demarcate utterances in a way that is more “natural” for using emoji than one giant continuous document!

It took me long enough to figure that out. The print form and structure are hard to shake off, even in digitized media. I was trying to think about how to punctuate when McCulloch’s interview came to mind. She commented that punctuating was not necessary for texting -emojis.