The potential relationship between media, education, text, and technology shifts my thoughts towards those displaced people that Canada provides refuge. Of those refugees, the single Sub-Saharan African mothers with their children live at the margins of Canada’s marginalized. These women function in an almost state of “primary orality” (Ong, 2002) arising from their meagre education. A lifetime of conflict, displacement, years of the encampment, and femaleness has exacted a heavy toll. “Secondary orality” (Ong, 2002) develops with their coming to Canada mainly through television and their cell phone that is permanently close at hand. Hopefully, most of this group will end up in Language Instruction for Newcomers to Canada (LINC) offered by the Government of Canada.

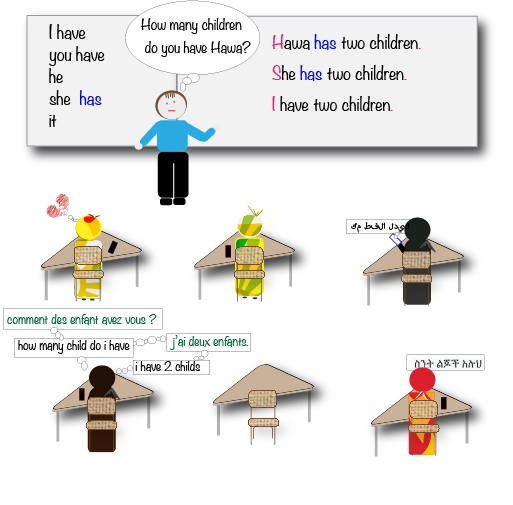

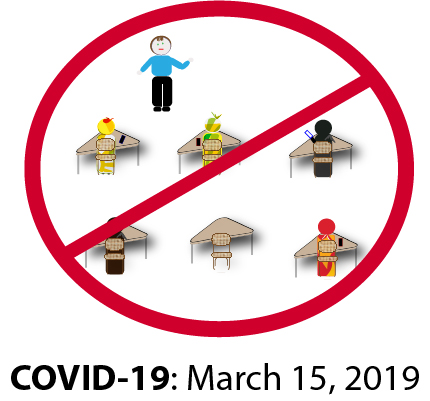

The federal program provides English instruction for those who need it. Classes are streamed for English level, but not for tertiary-educated nor refugee-camp-educated. This mixture potentially poses instructional challenges—as many still employ teacher-centred mass instruction. Furthermore, as a group, the refugee-camp-educated students’ progression pales compared to those who are well-versed in formal education and equipped with modern literacies.

I can read, write, and do arithmetic. And for most people, reading and writing is pretty straightforward. Arithmetic is pretty straightforward… As so even in today’s world, what we mean by literacy is highly conditioned on [your] life. -Doug Fisher

Unfortunately, a quieted griping could be heard amongst instructors ill-equipped to handle the discrepancy, let alone the despondency, forgetfulness, or exhaustion found within the classroom space. The tipping point for some was the incessant phone calls with animated unintelligible voices interrupting the sanctity of the occasion.

Literacy pedagogy … has been a carefully restricted to formalized, monolingual, monocultural, and rule-governed forms of language. –The New London Group

As a result, the Learners with Interrupted Formal Education (LIFE) classroom was created to work with students with low literacy, numeracy, technology, and learning in a formal environment. However, it was capped at ten students. Furthermore, admittance to the class was only through recommendations from regular stream instructors. Thus, it was not surprising that LIFE’s wait-list became long.

Our heroine is Hawa, a reserved woman from the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) who joined the LIFE classroom. Her previous instructor felt that her slow laboured responses were indicative of cognitive issues. Moreover, her neediness in the computer lab and constant phone interruptions were even more reasons for leaving the regular-stream. Little effort was given to knowing about her lived experience; it would cause discomfort, so canonicity and textuality (Scholes, 1992) were hidden behind.

Textuality refers to a collaboration between language and the human consciousness that always distances us from reality without ever replacing the reality. – Robert Scholes

who is this student in front of us

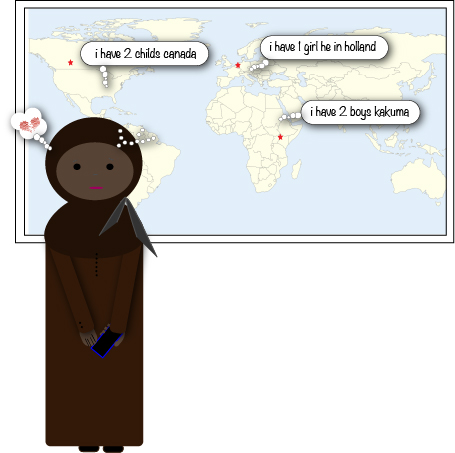

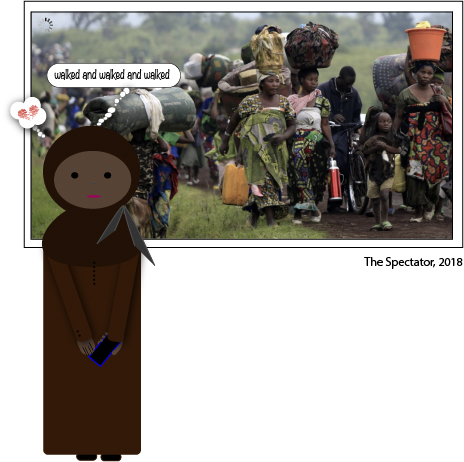

Like most of her classmates from other unsettled Sub-Saharan African countries, she had found safety from civil strife, ethnic cleansing, and genocides in Kakuma. Nevertheless, as a woman-headed household, she suffered from severe poverty. Moreover, as a refugee, she could not supplement the meagre UNHCR rations sustaining her family.

Kakuma was established for the Lost Boys of Sudan in 1992. By 2021, it has since surpassed its capacity of 60,000 by almost threefold necessitating sub-division. This influx has strained the camp’s infrastructure and resources, so clean water, food, and medicine are scarce (UNHCR, 2021). In addition, donor countries’ donations dwindle even though displaced people keep arriving.

She was four months pregnant when she left her village afoot with the seven children carrying parts of their life. They entered Kakuma emptied-handed after the exhausting trek across borders – it had been chosen because of rumours that settlement abroad was accessible through Kenya. Years passed before Canada accepted them for resettlement; the eldest three had reached the majority by then and had become ineligible. Only the eldest daughter had been able to find a third country, the Netherlands. The two sons remaining behind were still part of her monthly expenditures. In Canada, she heads a household with two pre-teen children and two youngsters abandoned to her care by their parents.

Canadians pat themselves on the back for their country’s generosity. And why not, after all, previous students, women-heads of households, had requested a counsellor at the school to help negotiate the paperwork needed for the three levels of government. Immigration Canada Refugee Citizenship (IRCC) came up with the funds. That counsellor had also secured Provincial Training Allowances (PTA) to help stabilize their lives while studying to improve their skill sets to become employable in Canada. Furthermore, the federal government had fulfilled the request to equip the LIFE classroom with technology such as Smart Screens and tablets to increase their digital skills. As a result, learning was swift, and some of the students even started to dream of a future.

A novel examines not reality, but existence is not what has occurred, existence is the realm of human possibilities, everything that [wo]man can become, everything [s]he’s capable of. – Milan Kundera

That was then and this is now

We Support Refugees! was a campaign for a Saskatoon mayor candidate a few years back. The premier echoed this slogan. Nevertheless, that was then, and this is now. At the same time as that campaign, the Saskatchewan provincial government stopped the PTA for refugees. As a result, some women found night employment as cleaners, and while they tried to continue studying during the day, they were often found asleep at their desks. Working, running a household, and studying was more than their bodies could handle. At the same time, others went on social assistance to keep afloat; it allowed them to continue their full-time studies. But there is a difference between PTA and Social Assistance governmental support; PTA requires the student to show up, like a job, to receive funding.

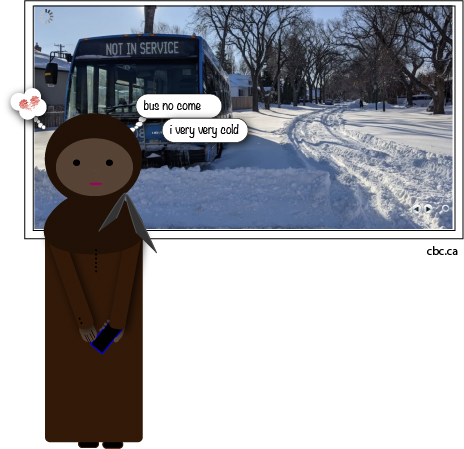

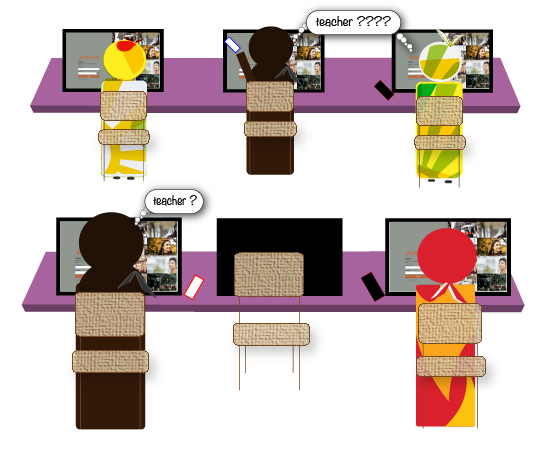

And then COVID-19 hit. A few of these over-aged female learners managed to finish the term: April, May, and June, but when the new period started in August, all the women had vanished. The reasons are numerous—for example, the cost of the internet is out of their range; they were relying on the free internet provided by the school. To study, they now needed to find access to free wifi: the local mall? Some had difficulty connecting to Zoom and the LMS with their phones.

In contrast, others had trouble doing the homework designed for desktops, laptops, and tablets but which did not function so efficiently on the phone. The tablets that they were using in class were squirred away for safekeeping. The dystopia for women like Hawa is already here. As educators and society, we must ask ourselves how their fate impacts their futures and what about their children’s future?

The mission of education … its fundamental purpose is to ensure that all students benefit from learning in ways that allow them to participate fully in public, community, and economic life. – New London Group

– Dune & Raby

Today, we don’t really have a person. We only have a person with a phone in hand. That’s the extended self… but by 2025 … our students will be extended selves. And of course, that has huge implicaitons for how we teach and even what we teach. – Jaco Hamman

The Life class had experienced the utopia before hitting the dystopia. True accessibility meets the students where they are with the technology that is at hand. It allows them to dream of a future and provides the possibility of realizing it.

dawn of a new age

As for our heroine, Hawa was hit by the loss of PTA and found employment as a cleaner. However, she was one of the lucky ones as she had moved through the system before COVID-19. When she needed to be transferred from the face-to-face format, her computer skills were strong enough for a blended-class design. At first, she was overwhelmed with the change but providing her with targetted help increased her confidence to work solo. She still was using only the phone, but the programs used were more phone friendly which decreased the troubleshooting required, thus reducing the frustration she experienced. As her English skills improved, she moved from the LINC program onto the Basic Education program and completed a primary caregiver and first aid certification. She is now employed in that field.

Pedagogy is a teaching and learning relationship that creates the potential for building learning conditions leading to full and equitable social participation. – The New London Group.

Evolving technology will improve learner agency, moving them to the centre of their educational process; thus, transcending away from a teacher-centred instruction from behaviourist glory. However, this requires educators to embrace the change.

The smartphone was a viable learning tool for Hawa as it is her sole digital technology outside of the classroom. This holds for many students found in the larger Canadian society. As O’Neil poignantly argued in the interview with Mars (n.d.), as educators, we need to evaluate the overall effects of our choices, evaluate for whom our options fail and know what harm falls upon them from that failure.

By working, Hawa eventually saved up enough money to purchase each of her children a smartphone plus subscribe to a family mobile plan with unlimited data. Her children taught her how to text and use the affordance of the phone, which kept changing with advancements like artificial intelligence, voice- and object- recognition, and the lithium battery capacity.

Nevertheless, she was still unsettled when the phone disappeared thirty years later. She felt odd talking into the digital wearable. But, on the other hand, she enjoyed the device’s capability of letting her chat with her sons’ and daughter’s holograms.

She appreciated her son’s driverless car taking her to work at the senior care home. It was more cost-effective and convenient than using the bus. In addition, she cooperated and collaborated with the intelligent affective-computing robotic humanoid at work. She was continually amazed at its ability to distinguish between the patients and staff, plus react and remember all their stories from their interactions.

Unlike the humanoid, she only remembered snippets about her childhood life. More importantly, she thought about the future that she had trouble understanding, but where she knew children would be a part of this new age of technology.

At work, Hawa always felt under surveillance. Nevertheless, she was safe in Canada; her biggest worries were her two sons in Kenya. The democratic government had been deposed, and the new regime monitored everyone. However, the country’s digital super-intelligence system efficiently handled the massive amounts of data collected from the digital devices in the country, the smart glasses of their agents who lived among the people, and the incessantly circulating drones—those who the government felt threatened by had brain chips implanted for continuous tracking. And more and more, those individuals talking about freedom and democracy were picked up by the police. These individuals were either reprogrammed or disappeared.

She worried for the worse as there was no place for her sons to hide from this ubiquitous surveillance and the heavy hand that controlled it.

With no regulatory oversight, the exponential advancements in technology are fueled by the profit of private tech owners. Technology holds promise but also worries about its dark and disturbing potential. As Elon Musk stated, we need to have a future where we get up and want to live.

References

Cazden, C., Cope, B., Fairclough, N., & Gee, Jim. (1996). A pedagogy of multiliteracies: Designing social futures. Harvard Educational Review, 66(1), 1–60.

Downey Jr., R. (2021, December 18). How far is Too Far | The age of A.I. https://youtu.be/UwsrzCVZAb8

Dunne, A., & Raby, F. (2013). Chapter 5: A methodological playground: Fictional worlds and thought experiments. In Speculative Everything: Design, Fiction, and Social Dreaming. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

Futurology. (2020, May 22). The world in 2050. https://youtu.be/RNVh_HMX2IY

Insane Cuiosity. (2020, February 27). The world in 2050: Future technology. https://youtu.be/Oa9aWdcCC4o

Mars, R. (n.d.). The Age of the Algorithm (No. 274). https://soundcloud.com/roman-mars/274-the-age-of-the-algorithm

Musk, E. (2017, May 3). The future we’re building—And boring. https://youtu.be/zIwLWfaAg-8

Ong, W. J. (2002). Chapter one: The Orality of language. In Orality and literacy: The technologizing of the word (pp. 1–11). Routledge.

Price, L. (2019). Books won’t die. https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/2019/09/17/books-wont-die/

Saskatoon Mayor Charlie Clark offers support to people. (2017, January 29). https://globalnews.ca/news/3212524/saskatoon-mayor-offers-support-to-assist-people-affected-by-u-s-refugee-ban/

Scholes, Robert. (1992). Canonicity and textuality. In Introduction to scholarship in Modern Languages (2nd ed., pp. 139–158). Modern Languages Association of America.

Tech Vision. (2020, June 26). The world in 2050: A peek into the future. https://youtu.be/nho3r9SjL7Y

UNHCR. (2021, April 1). Inside the world’s largest refugee camps. USA for UNHCR.