Background

Pesticide use can pose significant environmental externalities (3). Among other impacts is their effect on surface and groundwater contamination. Being a non-point source of such pollution, pesticide regulation is thus a complex policy issue.

In the 1980s, pesticides were a hotly debated topic in the Nordic countries. Although I am unable to find the precise trigger for such debate (I would appreciate if my readers would share any information on this), I found that Sweden was the first of these countries to formally address the environmental and health risks posed by pesticide overuse (4).

Introduced in 1984, the main goal of the pesticide tax was to reduce the usage of chemicals in the environment (1). Moreover, the tax revenues would be used to finance research and development of more environmentally benign practices, making pesticide reductions sustainable.

Specifically, Goal 1: By 1990, reduce consumption by 50% of the average of 1981-1985 levels; Goal 2: achieve further 50% reduction in consumption by 1996. In total, Sweden aimed for pesticide use reduction of 75% from before implementation of tax.

Implementation

The regulation was a Tax plus a Regulation Fee.

For the most part, the tax was administered as a fixed amount on every kilogram of active ingredient in the pesticide (1). Later, this was changed to a percentage of product price. The tax level changed many times since its introduction as summarized below (2).

- 1984: SEK 4/kg active substance

- 1988: SEK SEK 8/kg active substance

- 1994: SEK 20/kg active substance

- 1996: tax share is 8% of product price

- 1999: tax share is 5% of product price

Moreover, a regulation price was also initially charged to finance the administrative cost of implementing this regulation.

- 1991: SEK 46/ha dosage or 20% of the price of the pesticides

- 1993: converted into a tax

- 1995: abolished

- 1996: pesticide regulation fee

Sectors Covered and Exempted

The tax is applied at the retail level. It is imposed on manufacturers and importers of pesticides. Exempt from the tax are wood preservatives (1).

Appropriateness and Effectiveness

At first glance, it seems that consumption indeed decreased nearly 50% by 1991, as desired. Although the stated goal of 75% reduction was not achieved, the total consumption as of 1996 does seem to be 35% of average 1981-1985 level.

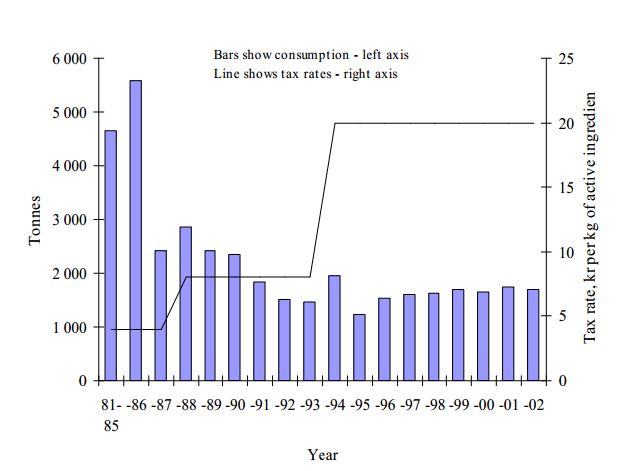

Figure taken from (1).

However, as we can see from the graph above, even when the tax rate more than doubled from 8 SEK to 20 SEK in 1994, there was no overall decrease in the volume of pesticides used. Instead, the Swedish Board of Agriculture and National Inspection found that farmers increased their purchases of low-dose pesticides (those that are biologically active at very low concentrations per hectare) (5). This was likely a result of the “soft effects” of the tax (4). That is, tax revenues were used to finance research that resulted in pesticides that were biologically active at low doses. Therefore, instead of looking at number of tonnes sold, if one were to examine the number of doses sold, there would be a definite increase since 1995 (4).

An obvious question that arises is whether a reduction in gross volume of pesticide use is equivalent to a reduction in risk to the environment or to health. A flat tax like the one implemented in Sweden treats all active ingredients the same, regardless of the level of environmental and health damage that they impose. It therefore merely encourages a shift from high to low volume products, which may in fact be more hazardous.

The more recent shift towards a tax as a percentage of pesticide prices may not be the particularly effective either, as prices may promptly decline as a result of technological change (that the tax revenue is funding!) (3), ultimately encouraging more pesticide use.

Therefore, rather than aiming for a reduction in tonnage of pesticide (active ingredient) used, a tax implemented on a hazard or estimated damage basis would be a more effective solution in my opinion. Even though I can see difficulties in estimating its value, such a tax would more explicitly address the social cost of the pesticide, rather than simply the quantity.

Moreover, the research and development which is being funded by the tax revenues would better achieve the stated goals if it was aimed at discovering pesticides which have lower damaging effects.

References

- http://epubl.ltu.se/1404-5508/2005/101/LTU-SHU-EX-05101-SE.pdf

- http://www.economicinstruments.com/index.php/land/article/135-

- http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTWRD/903845-1112344347411/20424145/31203ARDenoteWRMEIPearceKoundouri.pdf

- http://www.pan-europe.info/Archive/publications/PesticideTax.htm

- http://ec.europa.eu/environment/enveco/taxation/pdf/ch8_pesticides.pdf