Spatial Resurgence: Reflecting on Claiming Space

by Laura Mars

Walking through the museum of anthropology (MOA) to reach the Claiming Space exhibit was a dichotomous and affective experience. Standing in the central part of the museum, I was in full view of the lush xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam) lands that surround and house this campus, this city, myself and other settlers, and the Indigenous peoples of Turtle Island to whom the land is rightfully and inherently bound. I felt that I was being pulled in two directions. In the first I was overwhelmed by the beauty of these pieces, which remained powerful in spite of their context, and of the landscape surrounding them, which I am often astounded and overwhelmed by. In the second I understood the museum—and the presence of these stolen artifacts—as part of the system of settler-colonialism from which I benefit from continually as a settler, and through which Indigenous peoples are continually dispossessed. With these things in mind, I hurried through the first part of the museum, in hopeful pursuit of an exhibit that would contrast what seemed like the overarching theme of the so-called ‘permanent collection.’

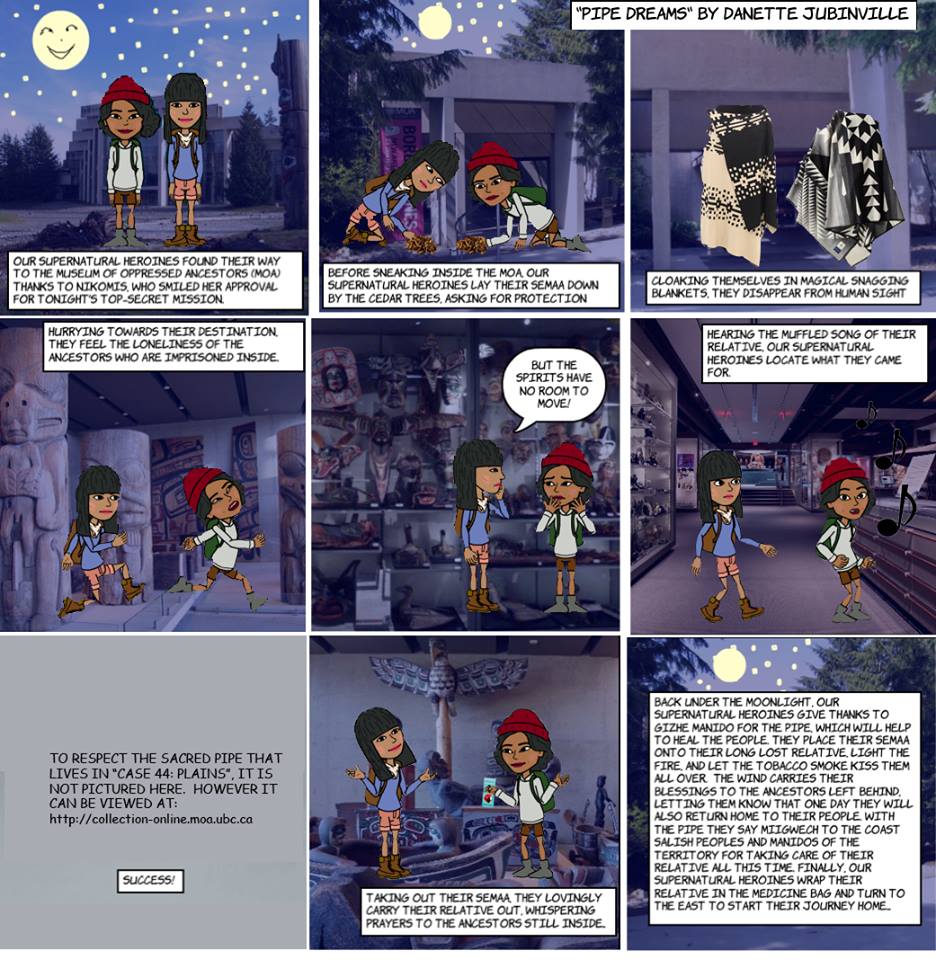

As I entered the Claiming Spaces: Voices of Aboriginal Youth exhibit, I immediately sensed a shift: this specific gallery was a site of Indigenous power, agency, and reclamation. As I walked through and observed art created by Indigenous youth, I was reminded of the work of Michi Saagig Nishnaabeg writer and scholar Leanne Betasamosake Simpson, who conceptualizes Indigenous resurgence through art as the creation of “decolonized time and space” (Simpson 96). In her book Dancing On Our Turtle’s Back: Stories of Nishnaabeg Re-Creation, Resurgence, and a New Emergence, Simpson discusses her experience viewing an exhibit titled Mapping Resistances – specifically the work of Nishnaabe performance artist Rebecca Belmore:

“[The piece] reminded us that we as Nishnaabeg people are living in political and cultural exile. Yet, it disrupted the narrative of normalized dispossession and intervened as Nishnaabeg presence — not as victim, but as a strong non-authoritarian Nishnaabekwe power…Indigenous artists like Belmore interrogate the space of empire, envisioning and performing ways out of it. Even if the performance only lasts twenty minutes, it is one more stone thrown in the water. It is a glimpse of a decolonized contemporary reality; it is a mirroring of what we can become.” (98)

I felt a similar disruption of this narrative of dispossession in Claiming Space, leaving room for the powerful message of Indigenous reclamation and resurgence. In Mixed Tribes, a zine created by the 2013 Native Youth Program students, Musqueam and Anishnaabe artist Kelsey Sparrow counters the complicated location of the exhibit within the walls of the museum of anthropology in her piece “This Is Not Native (?)”: “…if you want to go to Haida Gwaii because you love all the art here you should know that I have never met anyone in Charlotte City who really gives two shits about Bill Reid. This museum is about anthropology, not native people. You can learn about a part of us but not all.”

I viewed this exhibit as an incredibly necessary physical and temporal unsettling of an otherwise colonial space. Each work carried a powerful message of resurgence—even those, such as the video performance piece by Jeneen Frei Njootli, that unflinchingly tackled the ongoing effects of colonial violence upon Indigenous women in particular. I am turned back to Leanne Simpson and this idea of decolonized time and space, and art that is transformative. The Rebecca Belmore performance piece she is referring to in this discussion took place in Peterborough, which “is a bastion of colonialism” as experienced by Indigenous people (Simpson 97). “But,” Simpson says, “for twenty minutes in June, that bastion was transformed into an alternative space that provided a fertile bubble for envisioning and realizing Nishnaabeg visions of justice, voice, presence, and resurgence” (97). With a specific focus on the new medias that Indigenous youth are engaging with and shaping, Claiming Space is an important exhibit that is teeming with brilliant works of art and a powerful message of Indigenous resurgence.

_________________________________________________________________________

Belmore, Rebecca. X. 2010. Peterborough, Ontario. Performance.

Simpson, Leanne. Dancing On Our Turtle’s Back: Stories of Nishnaabeg Re-Creation, Resurgence, and a New Emergence. Winnipeg. ARP Books, 2011. Print.

Sparrow, Kelsey. “This Is Not Native (?).” Mixed Tribes. Museum of Anthropology Vancouver. 2013. Web.

_________________________________________________________________________

Laura Mars is a settler student and activist originally from former Yugoslavia, living on unceded Musqueam territory. A recent addition to the First Nations Studies program, she is in her fourth year of a double major in FNSP and GRSJ. She is interested in Indigenous new media studies, intentional communities, and anti-colonial feminisms.

Follow

Follow