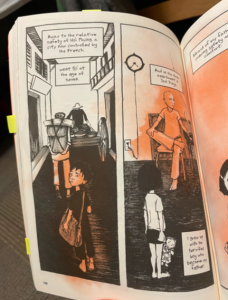

To start off second semester in my ASTU 100 class, we read The Best We Could Do, the graphic memoir by Thi Bui, which details the author’s family’s experience as refugees of the Vietnam War, and moving to America. On page 128 are two stark, vertical panels that take up the entire page, mirroring each other.

The first shows Thi Bui’s father, who she calls Bố, as a child, in a new city after escaping a dangerous invasion of his village. The second shows Thi herself in her childhood, watching her grown-up father smoking.

These two children, though many decades apart in time, are both fearful, in unfamiliar places with family members they do not fully trust as their only companions and protectors. By situating and displaying the two as so similar in these frames, Bui shows that from a young person’s perspective, they are not so different.

Both children are the same size, portrayed as equals. Yet with their dark hair (and in Bố’s case, clothes as well) they almost disappear into the dark ground—the eye is not first drawn to the children but rather their surroundings, the other characters in the scenes. They were not the center of the stories they were parts of at these times in their lives.Their similar stances are both timid in body language, though in different ways.

As well, the text on the page contributes to this feeling that these timelines are impossible simultaneously. The start of the second panel, “And in the dark apartment in San Diego,” evokes an unwritten “meanwhile” between the two panels. Bui even directly mentions that “the terrified boy who became [her] father” was there with her as a child, more than the adult he should have been in the situation.

The similarities between the children are much more visible than the ones between Thi and her father in the second panel. They could almost be companions, yet this is a connection that Bui shows she only felt later in life upon reflection. Even as they are so physically close and similar on the page, the children are facing away from each other, with no knowledge of each other. In childhood, Thi Bui could not find comfort in her father.

This is such an interesting dive into the novel! Examples of Bui’s complex relationship with her father are found throughout the novel, but this is one of the best examples. I never examined this page like you did, so reading this was fascinating. It’s also interesting that Bố would look away in his panel (almost searching for something?) while Thi looks at him in hers (as if searching for something in him). Great analysis!

– Asina

Hi Jaqi! Really great analysis, I loved it. Thi Bui and her relationship with her father is such an important part in The Best We Could Do and you explained it very effectively. The page you chose was excellent in subtly describing their relationship, and there is so much to be gleaned from something that looks so simple. The colors in particular really stood out to me—that Bo is illustrated with that trademark rusty red color—and his position in the panel shows that the roles have been flipped in a way. I think that symbolizes the topic of generational trauma you and Thi Bui are going for. Again, loved your post!

Wow! I really love this analysis of the page. The contrast as well as comparison as Thi Bui’s childhood compared to her fathers is stark – and I love how you were able to find a page that embodies their relationship perfectly. It is kind of beautifully tragic how we can see clearly represented that they were- at least one point in time- somewhat similar, “background characters in their own story.” And yet they are still divided, their paths are still separate – perhaps this was demonstrated through the choice of having 2 separate panels as opposed to one larger connected one, which would have instead signified their two worlds were “connected.” I also agree that the symbolism of them facing away from each other is strong, and I never would’ve picked up on it if you hadn’t pointed it out! The colour usage (them fading in to the background) was another fine detail that really amplified just how “unimportant” they are. I think it is really really cool how the author can use different visual tricks, such as drawing our eye to one spot first, to completely change the meaning of a text or page. Overall excellent blog post, I enjoyed reading, thank you so much!

Hi Jaqi! I really like your blog post! It was after reading your blog post that helped me realized though having their childhoods in different eras, Bo’s and Thi’s childhoods were pretty similar- that they could’t find comfort from their dads. Their fathers to a certain point both fit into my “Asian parents stereotype”, which parents (especially dads) tends to be very strict and they love keeping a certain distance from their kids in order to establish their “figure”. I would say the reason contributing to this is probably is the culture in most Asian countries throughout the history revolve around having a strict hierarchy (mostly about having dominant men), not only on society, but also within a family. I’m not here to judge whether having such a culture is right or wrong, but it is interesting to notice difference in different parts of the world.

-Gordon Mok