This past weekend I volunteered at the CAP-C conference hosted at Frog Hollow Neighborhood House whose theme was ‘Healthy Families, Happy Future’. One of the activities involved information booths on various topics such as post-partum depression, staying active, gardening, eating grains, Canada’s Food Guide, eating breakfast, cooking healthy while on a budget and so on. Out of 61 parents that registered for the conference, only 2 were Dads, while the rest were all women with children between the ages of 0-6.

I was told by the coordinator of family programs, Lea Laberge that the theme for the conference had been picked by parents and program participants a few months ago, and while I expected it to be female dominated, I had no idea that ratio of Mothers to Fathers would be so skewed. In Global Woman, Rhacel Salazar Parrenas describes the care crisis in the Philippines as a product of the economically motivated migration of women in order to provide for their children back home by sending remittances. She says that there is a growing trend within developing nations in which economically, women are afforded more equality, often heading up the family and acting as the sole breadwinner, but they are held back by gendered cultural and religious ideals that construct them as morally bankrupt for depriving their children from the kind of love and care that only a mother can provide (Parrenas 2002: 52).

And while I do not mean to discount the difficulties women in the developing world face when they leave the domestic sphere in order to seek employment, after attending the conference this weekend, I think that it would be interesting to consider the pressures that immigrant women in Canada face. Often we allow ourselves to believe that Canadian society is free of the ridged gender binaries that consider women to be the primary caretakers of children and nurturers of the family. And yet, while at a conference concerning the health and welfare of young children which was open and accessible to all members of the community, the mostly female turnout evidences that ‘care’ remains a gendered concept in Canadian culture as well.

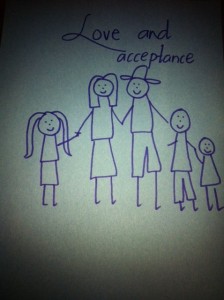

The station I ran at the conference was concerned with body image, and encouraging an inclusive view of beauty. The women that I spoke with told me stories about their daughters mostly, and you could tell how much they were pained by their daughters’ physical insecurities. One mother told me about how her daughter cried to her all the time while she was living with another family because they were all white and she wasn’t. When I asked the women to draw what what beautiful about themselves, many drew their families, or their children [see Figure 1] which to me signified a selfless existence, one in which ‘beauty’ was not a physical attribute but a lived experience, one for which these women are willing to hard for. And while this is by no means a significant statistical sample, but I would like to suggest that there is a reason that family health was voted as the topic of the conference and concurrently so, there is a reason that mostly women showed up to learn about how to prevent cavities in their children’s teeth, garden, encourage good self esteem, cook and shop for nutritious foods.

The station I ran at the conference was concerned with body image, and encouraging an inclusive view of beauty. The women that I spoke with told me stories about their daughters mostly, and you could tell how much they were pained by their daughters’ physical insecurities. One mother told me about how her daughter cried to her all the time while she was living with another family because they were all white and she wasn’t. When I asked the women to draw what what beautiful about themselves, many drew their families, or their children [see Figure 1] which to me signified a selfless existence, one in which ‘beauty’ was not a physical attribute but a lived experience, one for which these women are willing to hard for. And while this is by no means a significant statistical sample, but I would like to suggest that there is a reason that family health was voted as the topic of the conference and concurrently so, there is a reason that mostly women showed up to learn about how to prevent cavities in their children’s teeth, garden, encourage good self esteem, cook and shop for nutritious foods.