This past Saturday I volunteered at the Community Action Program for Children (CAPC) conference. This year the conference focused on health education and activities for parents. The annual conference welcomes members, staff, and volunteers from other neighborhood houses, giving participants an opportunity to meet and mingle with people from both in and outside their own communities. Coordinator of family programs at Frog Hollow, Lea Laberge explains how the day is a rare opportunity for parents to have “adult time” as child minding is provided for the duration of the conference.

As UBC volunteers, it was our job to prepare and present posters and information on different health issues faced by parents and their children. Stations ranging from car safety to healthy eating formed a path through the room. Participants were divided into three groups and the conference was divided into three parts. In the largest room, one group was to walk around, visiting displays promoting health. As they would visit, we (UBC volunteers) would talk with them about the different issues. In another room the second group watched a video presentation and had a discussion about ovarian cancer awareness and prevention. In the kitchen, the third group watched a cooking demonstration. Once each group had participated in each of the activities, they split into two groups: one doing yoga and one doing arts and crafts. It was at this point in the long day, nearing the end that I really felt and saw the impact of the day. The arts and crafts workshop was a the perfect relaxing ending to an informative and interactive day. Everyone had a great time creating their works of art and parents seemed to fully enjoy their day of learning and relaxation.

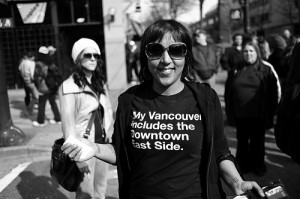

Although my final project is not directly related to my neighborhood house placement, my time spent there has definitely helped me to understand similar themes in my mother’s story of immigrating to Canada. In 1967, after fleeing to Canada in hopes of a better life for an interracial couple, and as an act of opposition to the Vietnam war, my parents became immigrants in Canada. After my parents divorced, my mother, who was raising six children on her own, decided to go back to school. During this time of readjustment, my mother relied a great deal on community and community programs. Many of these programs were available to new immigrant families. It was at these events and programs that my siblings and I met many of our friends. It was also at these events that my mother built strong friendships and networks, and where her passion and commitment for social justice re-emerged. As an African American woman, my mother was used to adversity and although her experiences of hardship and discrimination were harsher in the place she emigrated from, as a visible minority in Canada, my mother shared many similar experiences with other immigrant women and families.

In their article Neighbourhood Houses and Bridging Social Ties, S.R. Lauer and M.C. Yan explain how voluntary associations and programs “are important creations for tie creation. These organizations bring people together to form new non-kin ties and therefore offer the possibility for creating diverse personal networks.” As my final project will show, and as the CAPC conference proved to me, these programs are not only important in providing access to information and resources, they are as, if not more important in providing spaces where people can meet, make friends, and build new communities.

Lauer. S.R. & Yan, M.C. 2007. Neighbourhood Houses and Social Ties. Centre of Excellence for Research on Immigration and Diversity: Working Paper Series. pp. 5-34.