The first time I saw Francisca, I saw a woman of the Mapuche culture from Chile. For me, her physical resemblance with the “people of the land” (1) from my country was very clear. Even her clothes looked familiar. I approached her with this assumption in my mind. I was expecting a cold and disparaging reception, because for many Mapuche people I would be considered a “huinca” – a foreigner and usurper. This opinion/classification is supported by a violent history of oppression by Spanish colonists and present exclusionary social dynamics. But when I saw her relaxed and welcoming, I realized that I needed to be open to her particular worldview, which could be very different from my previous references and experiences.

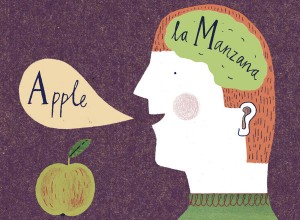

After realizing how my previous experiences could shape my observation, I focused on discovering the patterns and dynamics of the people working at the farm. Observing both groups, the volunteers from the Urban Farmers Program and the people from the Maya Garden, I realized that everyone has a migration story. For example, most volunteers came to Vancouver from distant and neighbouring cities of Canada, and the most common reason to move was to study. This challenged my first assumption that the migration stories were only present in the experiences of people from Guatemala working at the Maya Garden.

Besides ethnicity, there is a clear difference among the two groups of people I am observing in the farm. This difference is the time they spend, or have spent, working on the farm. While volunteers from Urban Farmers Program spend three to twelve hours on the farm in one season, the people from the Maya Garden have been working on the farm for eleven years. They told me that after all these years, they felt a sense of place and belonging, but it was not the same at the beginning. It took time to develop this relationship with the place, but now they plant and grow their traditional seeds in the garden using traditional methods; do their traditional ceremonies; and communicate with each other in Maya language. I think the farm cultivates this paradox, in which “locals” feel like “immigrants”, and “immigrants” feel like “locals”. In this regard, so far I could say that what makes you “local” is time in contact with the ground and your traditions. In this sense, when I say local, I mean having a sense of belonging in a place. But what happens outside the piece of land called Maya Garden? Do they become immigrants when they are outside of this garden? Is the experience of the Maya Garden enough to confer them a sense of place and belonging in a new nation? So far, I can only say the Maya Garden is the place where this group of people can grow the food they are used to eat and like, and do the activities that they were used to do. By the way, I wonder if the younger relatives of this group feel the same need to work the land as the elders do.

(1) In Mapudungun (Mapuche language), “mapu” means land, and “che” means people. (www.mapuche-nation.org/english/main/feature/m_nation.htm)