This semester, I am working to improve my written feedback practices. I have just under 30 students in a second-year course that is “writing-intensive,” i.e., designed to improve their academic writing skills. This means that nearly every week, students are completing a short writing assignment, and nearly every week, I have the opportunity to offer them feedback.

Everyone’s heard something about feedback strategies like “two stars and a wish” or the “good-bad-good sandwich.” Advice like this reminds us to balance positive reinforcement with corrective remarks, and to limit the number of suggestions we make so that students can actually act on them.

While I am always striving to give my students great feedback comments, this semester I am taking a step back to look at how I can use feedback to develop my students’ self-regulated learning.

After finishing an assignment, no student is an empty vessel waiting to receive feedback from their instructor. They already have plenty of ideas about what was hard and what was easy; what they did well and what they did poorly; and why that was the case. Just stand outside a classroom where an exam has just finished and you’ll hear plenty of conversations around self-regulated learning.

My goal is to provide written feedback that helps students have these conversations with themselves. I intend to do this in the context of their writing assignments by writing comments that show my students “how a reader (the teacher) experienced the essay as it was read (i.e. playing back to the student how the essay worked)” (Nicol and Macfarlane-Dick 2006, 209). This mode—really, a mindset—of writing comments on essays can, if successful, reveal to students the conscious or unconscious choices that have impacted their writing. The end result, hopefully, would give students concrete, actionable ways “to reduce the discrepancy between their intentions and the resulting effects” of their writing (ibid., 208).

What this kind of feedback looks like in practice, I am still working out. However, I know that it will NOT look like this:

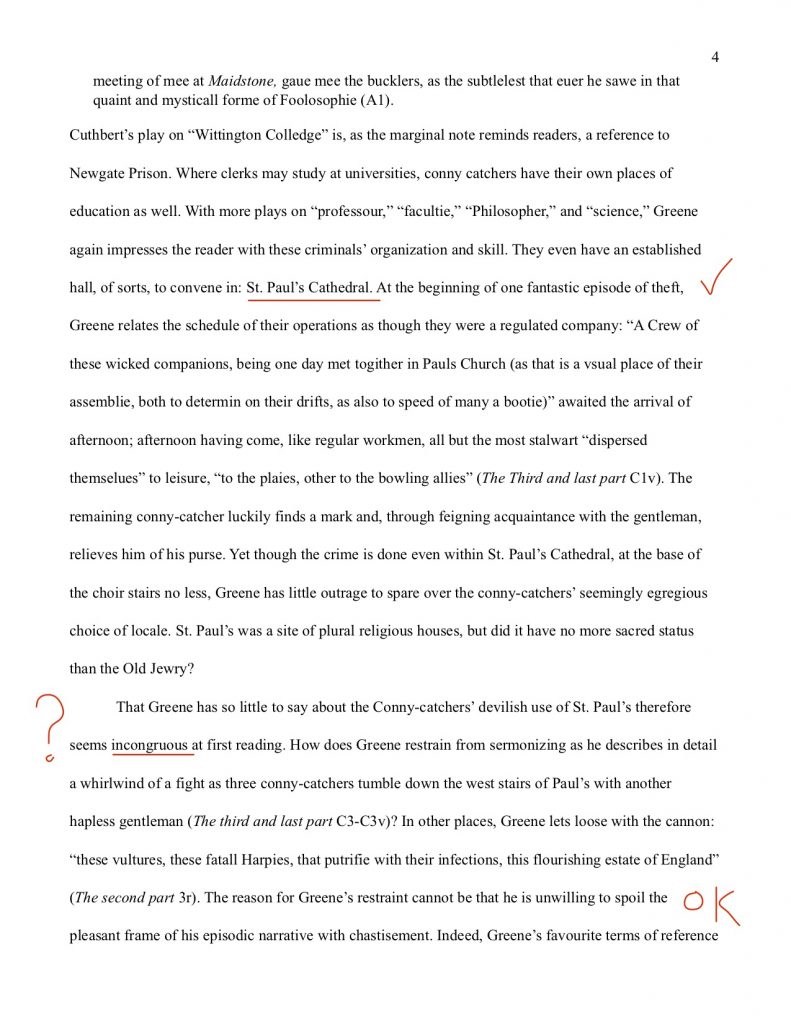

Scary comments on an essay

Checkmarks, squiggles, underlines, questionmarks, laconic comments. I dreaded the “OK” comment! Was it an “ok… but” or an “ok, great!” or an “ok, just barely acceptable”? But sometimes, it is good to work from a negative model as well as a positive one.

Specifically, here are some components I am trying to incorporate into my written feedback:

- Signpost comments: “at this point in the essay, I am expecting you to [do this]”; “above, you said this… so I hope that here you will [do this]…”

- Clear, unambiguous notations: make a clear distinction between positive and negative aspects of the reader’s experience

- A non-authoritative tone: helps to cultivate in students a sense of their readers’ experience, not their teachers’ experience

- Reading for intentions: it is not always apparent what a writer actually wants to accomplish; its an instructor’s goal to help them find that intention and accomplish it.

With respect to this last component, reading for intention, I found a lot of success by following a recommendation from Carolyn Samuel, who is a part of the Teaching and Learning community at McGill University. In the last assignment, I asked students to self-annotate their writing by underlining their thesis statements before submission. This encourages students to enter into dialogue with themselves about their intentions in writing, before receiving any feedback from the instructor.

I am also planning to ask my students to offer feedback on MY feedback at the midway point of the term (yikes, that’s VERY soon). I will follow-up with a midterm post that includes their thoughts.

Notes:

Nicol, D. J. and Macfarlane-Dick, D. (2006), “Formative assessment and self-regulated learning: a model and seven principles of good feedback practice,” Studies in Higher Education 31(2): 199-218. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070600572090