I am a specialist in Early Medieval European history, particularly during the reigns of the Frankish kings Charlemagne (768-814) and his son, Louis the Pious (814-840).

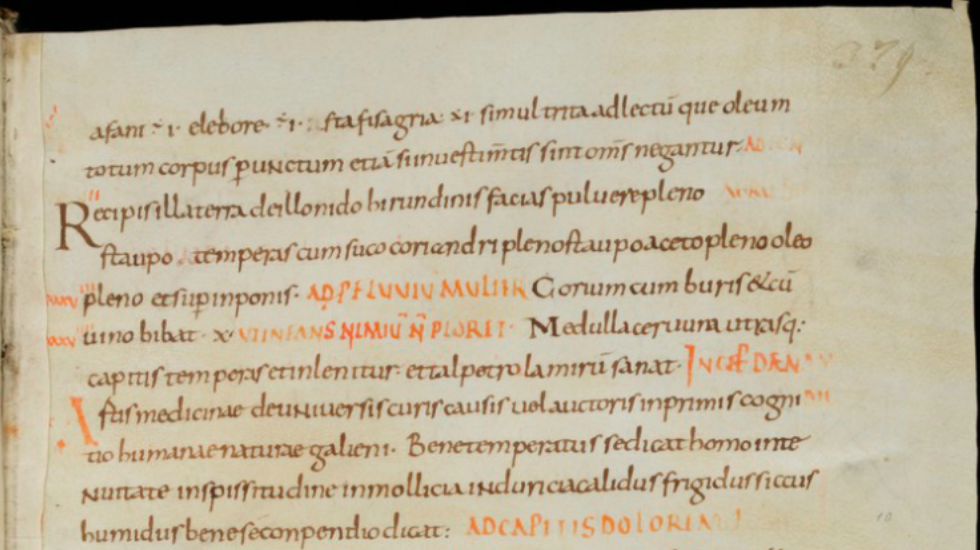

During my MA (University of Toronto), I studied the history of medicine in this period, specifically the formation of a new pharmacological/therapeutic textual canon (the dynamidia) that was then popularized by the doctors at Salerno, Europe’s first famous centre for medical education. Tracing the growth of medical knowledge during this period requires reading medieval manuscripts with a very open mind. These books are rarely neatly organized. Rather, a huge number different texts and recipes, often dating from the Roman period, poorly translated from Greek into Latin, and some just a paragraph long, were (literally) sewn together in an attempt to make the best available reference-guide for the ninth-century physician out of the very limited resources available.

A dynamidia-book of recipes begins after a remedy for a baby who cries too much. Source: e-codices.unifr.ch

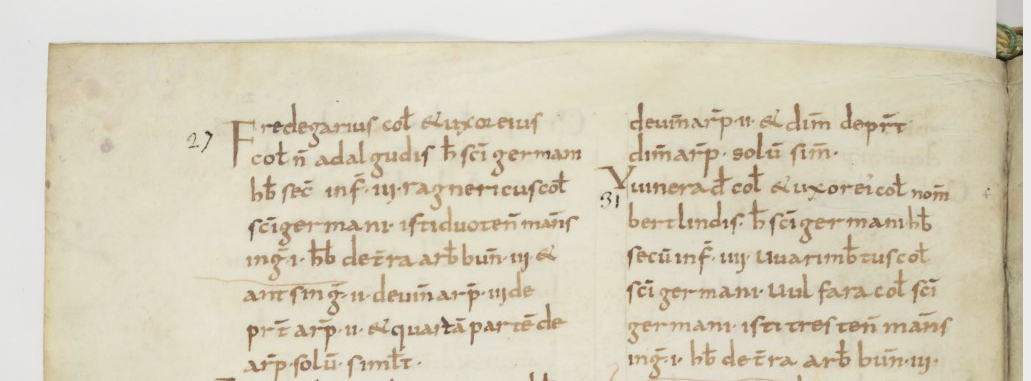

In my doctoral research, I’m continuing to work with manuscript evidence, but of a different genre. The agricultural administrative records created by the largest land-owning monasteries of the ninth century (called polyptyques) are excellent evidence for the information gathering practices of early medieval states, and they have traditionally been an invaluable source for economic and demographic history. They offer detailed information about the workings of the early medieval manorial economy and even clues about the origins of the European Marriage Pattern.

The entry in the polyptyque of Saint Germain-des-Près for Fredegarius, his wife Adalgudis, and their three children (top left). A single man, Ragnericus, also lived with them on their farm, which included arable land, vineyards, and meadows. Source: gallica.bnf.fr

However, the polyptyques are also a source of mysteries. Historians have observed that the largest of these documents, which records the men, women, and even children living in 2,600 different households, presents a historically anomalous and dramatically unbalanced sex ratio (approximately 127 men to every 100 women, whereas the norm is about 105 at birth and parity later in the life cycle).

Where are the missing women in these polyptyques? I am investigating the various explanations historians have offered, from mass infanticide, to female corvée labour in textile workshops, to historically gender-biased under-reporting of women. I am broadening the data-set to include more polyptyques than have previously been studied from this angle, and I am also developing a comparative study of historical parallels: for instance, the late Roman Egyptian census documents, and the Anglo-Norman Domesday Book. By studying the role of gender in the recording practices of pre-modern states, my research will provide much-needed context to the future work of historical demographers, sociologists, and both social and economic historians.