Getty Images

Happy New Year!

A new year brings a new semester, and a new semester brings brand-new students and courses. I often feel like the last semester ended just as students were beginning to feel really comfortable in the space of the classroom and with each other. Despite the usual end-of-semester stresses, my students were smiling. They were engaging with one another. They were making jokes. More than volunteering answers to my questions, they were posing questions to each other. If only every class had the same level of engagement as those classes in the last few weeks of the term!

Now, however, we have to press rewind. (Unless you teach full-year courses, in which case I don’t know if I should feel envy.) It’s the first day of school all over again. Students have to find their legs in a brand new course, and as instructors we have to help them. This year, I’m committing to foster better group dynamics in my classrooms, sooner. That’s why I thought carefully about the first day of class—because it’s the first day not only for my students, but also for me.

How do you teach the first day of a new course? More specifically, how do you teach the first day of a new course in order to accelerate group dynamics? These changes would eventually occur after the same group of people has been meeting together once or twice every week for two months, but how can we get to that good group feeling, earlier?

I can tell you how some first days are taught. The instructor reviews the syllabus, going over the textbook—yes, I know it’s not in the university bookstore yet, but they said they’re working on it—the weekly assignments, the schedule of exams, and major projects or papers. A few sneaky typos from the previous iteration of the syllabus are corrected—no need to fret. Are there any questions? Okay then. Class is dismissed early.

This is the first day of class as held in many large courses and also in smaller, discussion-based seminars. Logistically, this first day makes sense. Students will only be successful if they know the requirements for achieving success in the course. Since as a student I never once read a syllabus from front to back, I would assume that my students don’t do that either. Covering that critical information during class time can seem necessary.

However, this semester I did not address the syllabus at all. Since I lead the weekly small-group discussions of a larger course of approximately 100 students, the lead instructor had that particular honour. I also avoided the routine round-table introductions so common to discussion-based classes, tutorials, and seminars. (Hi, my name is Jacob. I study History. I’m in the 2nd year of my PhD. I took this class because…) Only time will tell if this first day achieved its goals. Here is what I did.

(Disclaimer: my classes usually have 15-20 students. Small size is definitely a luxury in lesson-planning.)

1. Icebreaker. Groan, right? Well, I think my students actually had fun with this one. I skipped introductions entirely and divided the students into small groups. Using the whiteboards in the classroom, students first wrote their name on the board, and then had to quickly draw clues that would help their teammates guess the answer to the prompting questions. I wrote up a list of fifteen questions, some of which were basic introductory boilerplate (favorite food; favorite hobby) and some of which were a little more “out there” (if you could be an animal, which would you be?), and pinned several copies to the board. Each student only had two minutes to draw, and couldn’t talk or write any words! If this sounds like Pictionary, that’s because it is. Someone did actually make it through the whole list in only two minutes! Judging by the laughter I heard, I think this icebreaker was successful.

Icebreakers are most important because they reduce the stress and discomfort of playing the role of a stranger around strangers. In small, discussion-based classes it’s particularly critical that the participants feel comfortable. My goal with this icebreaker was to use small groups first as a launching pads for the launch group, and to remove the barrier to “silliness” that can stultify group dynamics. In fact, sometimes the silliest icebreakers are the best.

~

After the icebreaker, I took attendance in the old-fashioned way. I still don’t know my students names, and addressing them by name is for me the best way to learn them. I briefly explained the format and rationale of these “tutorials,” as we call them: small group discussions that are intended to allow students to explore topics in more depth than might be covered during lecture. At this point I also allowed a pause for any general questions about the course.

With the “purpose” of the class now in mind, I moved on to the next activity.

~

2. Goal-setting. Courses are designed to achieve specific learning objectives, but they can lead to unspecified learning outcomes for students as well. With this activity, I hoped to facilitate those learning outcomes. I asked students to take a few minutes to think about what they hope to learn from this course. Are they looking for specific content knowledge? To get more practice or help improving a particular skill? To have more opportunities to do something that they feel they excel at? The students wrote their thoughts on index cards that I collected at the end of class.

I didn’t share these goals with the class. This was a private, individual activity. Instead, I took the goals cards home with me and reviewed them. For my own reference, I made notes about common themes among the cards and the goals of each student. In a future class, midway through the term, I will return these goals cards to the students and ask them to check-in with themselves. Have we made any progress towards their goal? If yes, that’s great: positive reinforcement. If not, what can I do as an instructor to help?

This has potential benefit for learners and for instructors. It is another way to be accountable for students’ learning beyond their grades. I haven’t ever tried this before, so I will be interested in my students’ responses later in the term.

~

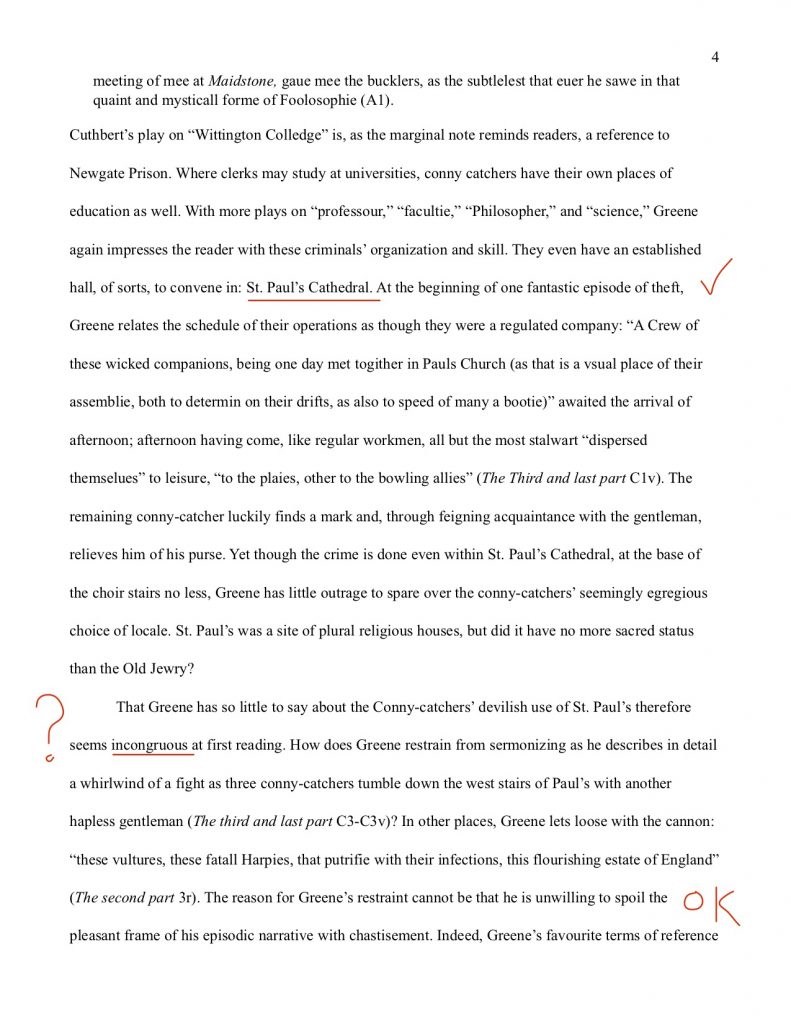

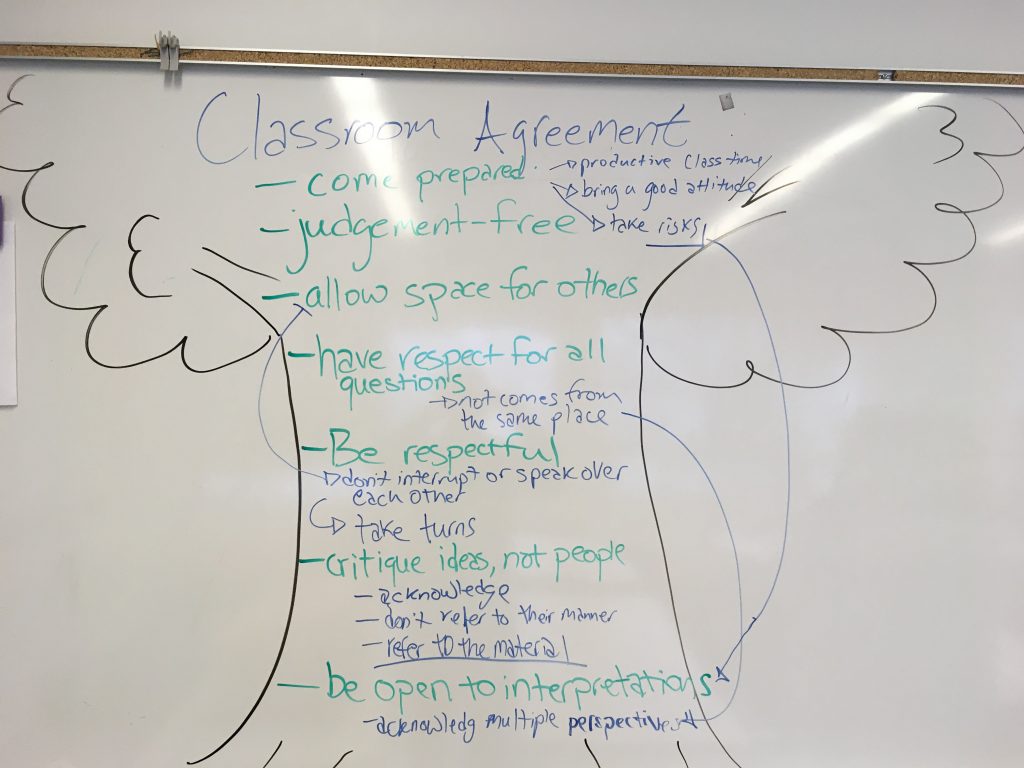

3. Collaborative classroom agreement. I asked the students to reflect on what that they need to happen, or not to happen, in the classroom to help them reach their goal. Each student wrote their thoughts on the back of their card.

I designated a space on the whiteboard by writing “Classroom Agreement.” I asked the students to volunteer some of what they had written, in order to collaboratively generate an agreement for the kind of space that we would cultivate in the classroom. I wrote their thoughts on the board.

As I wrote, it became important to ask students for more detail. What does a “respectful environment” look like? Why is being respectful important for learning? How can we show that we are being respectful? While I provided these prompts, I left the answers up to the students. I noted them on the board. We had a small discussion about each point as it went up on the board, and I offered lots of space for students to ask clarifying questions or voice concerns.

The classroom agreement made by one of my classes

As it turned out, both of my classes built very similar agreements. In fact, I would have been more surprised if they were radically different. But if half of this activity’s value lies in the literal agreement itself, the other half is in the process of actually doing the activity. The goal of this activity is to verbalize what we take for granted, and to give students ownership of the classroom and their behavior.

~

By this point, we had almost reached the end of a 50-minute class period. These activities can take quite some time, but in fact I spent very little time talking! At the end of class, I allowed some more empty time for students to ask those logistical questions about the course that hadn’t been addressed yet.

Only time will tell if this first day has set up these classes for success, but I’m looking forward to seeing how they develop.