“Layering” refers to a style of virtual, synchronous classroom where students and instructors use two platforms at the same time: for example, Zoom and Google Docs. Students run video/audio through Zoom, but edit a Google Doc collaboratively. (Watching a YouTube video of puppies while on a Zoom call does not count as layering.) Most of us have probably been doing this already in our roles outside the classroom, in meetings with our colleagues and with other professionals. But, the pedagogical applications of layering are very exciting.

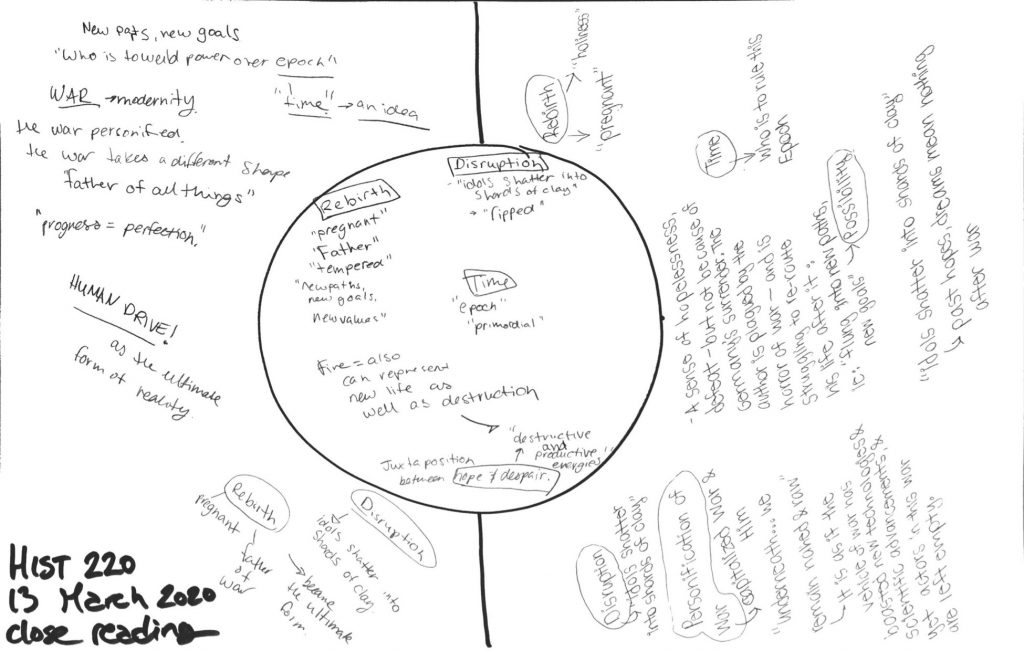

When I last posted here, I was already nostalgic for the time when we met face-to-face in physical classrooms. And I was lamenting the loss of those material supports for learning that I had recently begun to incorporate into my classes—those worksheets and diagrams, mindmaps and group-work templates printed out on paper. Before launching into our weekly discussions, my students tracked their thinking on the paper in front of them, and when the conversation started they had a physical map of where their thoughts had gone (and if they continued to take notes, of where their thoughts were going).

I appreciated adding material supports for learning into my classroom because: They boosted participation. They offered another way to participate for students who did not want to speak out that day. And, they ended up as physical reminders of the work we had done that day, which helped turn the often fleeting, ephemeral experience of a Humanities tutorial into a more concrete endeavor.

In the last few months, however, I have been a total sponge. The e-Learning knowledge of my colleagues on the Graduate Student Facilitation team at CTLT has been completely inspiring. I’ve seen lots of different methods of layering and I want to share a few simple ones that really made an impact on me.

- Google Slides. The workshop facilitators at CTLT have made great use of Google Slides for layering active participation into their sessions. Participants are given an edit-permissions link to the same slideshow that the facilitators are using to run the session. The facilitators, meanwhile, created slides with templates for the activity. The benefit? Both the slides with the instructions for the activity, and the activity itself, are in the same place! Participants can see the context of their activity within the workshop by viewing the previous slides. At the end of the session, the facilitators send out the new slideshow that has been completed with participants’ contributions—a record of our notes and thoughts while we were in the workshop.

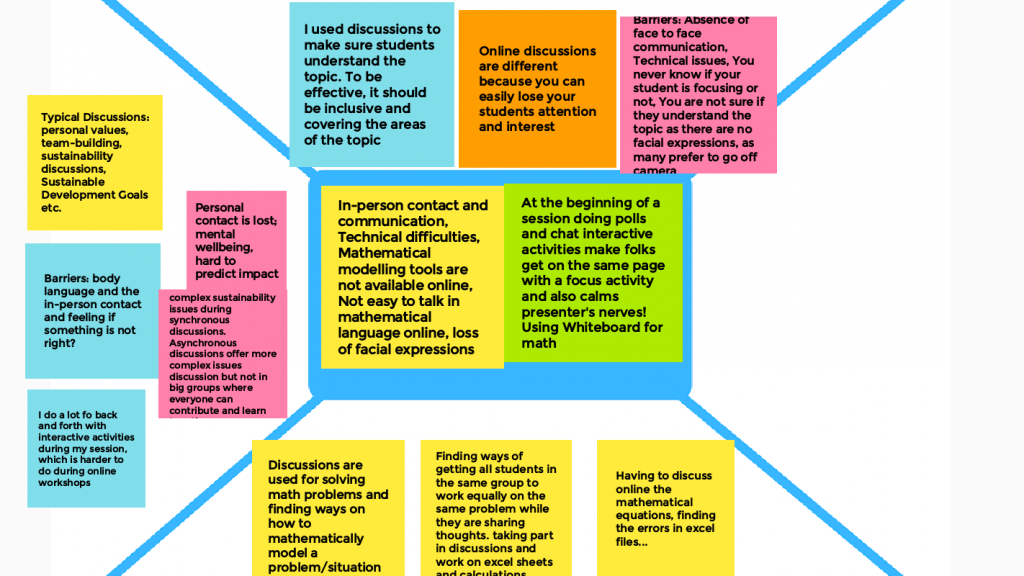

- Stormboard / Google Jamboard / Padlet. These platforms are all for creating mindmaps. Each has its own features and functionality, but the basic mechanics are simple: users write text into a sticky note which then appears on a blank background. They can resize, color-code, and move the sticky note around. Users can also doodle and add shapes. In a recent workshop that I co-designed this May, we recreated the “Placemat” activity on Google Jamboards. We asked participants to brainstorm barriers to participating in online discussions and then help each other discover some potential solutions. Yellow stickies represent the “problems” and green stickies represent the “solutions.”

A “placemat” activity rendered in Google Jamboards

- Close-reading on Google Docs. With a Commenter permissions link to a Google Doc, students can add notes to a copy of a text (a historical document, a poem, a passage from a novel or a speech) that the instructor has copied into a Google Drive document. These comments can be used to do close-reading of texts, and since comments can be threaded, instructors can use their own comments to suggest prompting questions, and students can reply to those questions within the thread. This would work equally well as an asychronous activity, but in a synchronous session the instructor can make connections between students’ contributions and ask students to expand or offer clarification of their comments.

The most significant drawback of layering platforms in synchronous classrooms is bandwidth limitations. Not all students—and not all instructors, for that matter!—have a strong enough internet connection to balance a Zoom call with another synchronous editing platform like Google Docs.

For that reason, layering should be a non-critical form of participation (i.e., not worth significant marks). Some of the simpler aspects of layering can be achieved with the annotation tools that are built into Zoom, and Blackboard Collaborate Ultra.