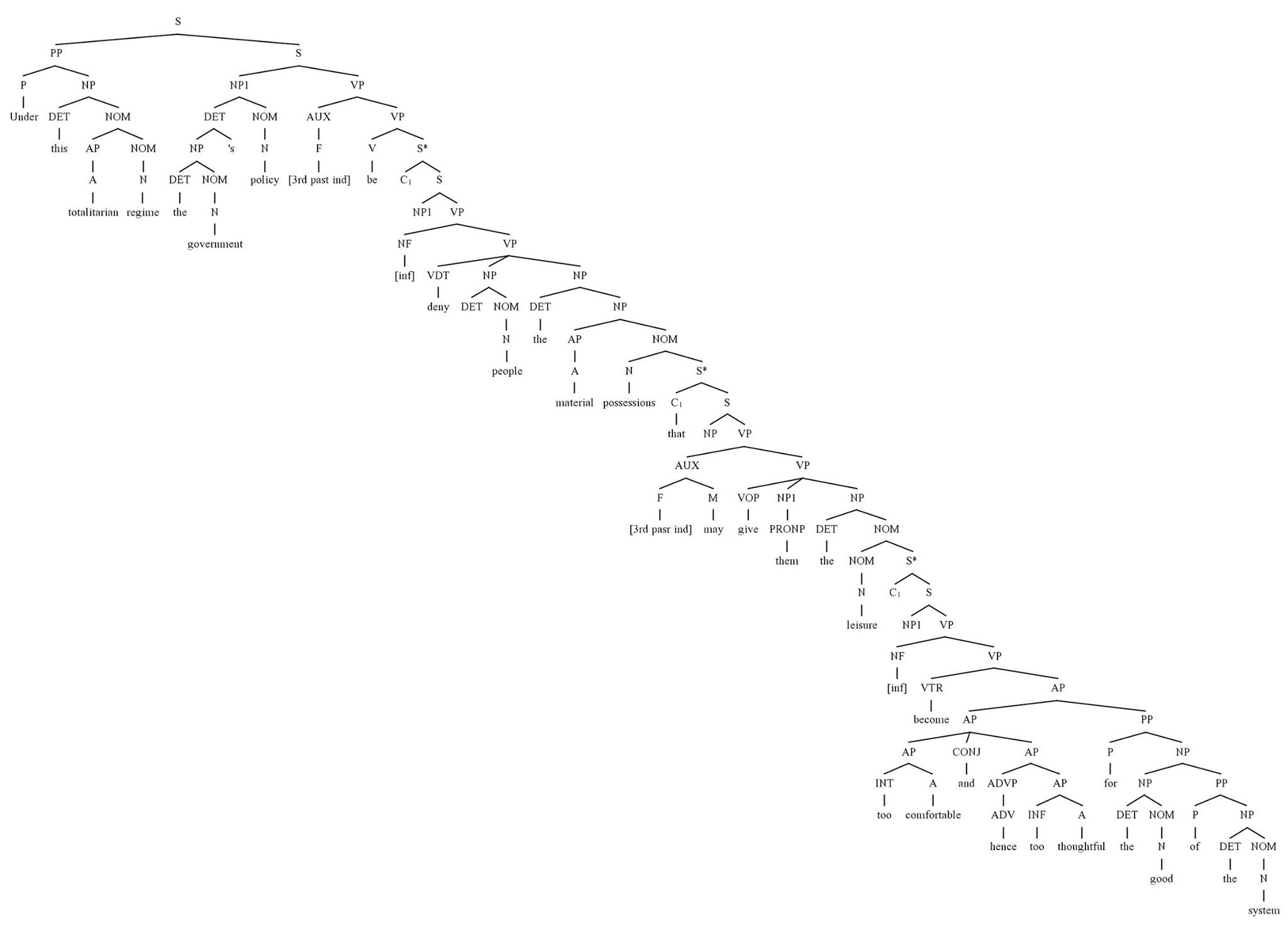

I grew up bilingual, and spoke 6 languages by the time I was 10. Language was always so lovely to me, and growing up in a country with 11 official languages meant that multilingualism was simply just a way of life for many of us. My mother was also a speech therapist and audiologist, who specialised in early intervention, and I spent many days in her private practice listening to her develop language and communication systems with children who were “never meant to” be able to speak. This thread wove through my life, ending up with me doing my undergraduate in Linguistics, where I learned a good many new interesting things. Including how to make these very crazy looking syntax trees, to try and describe and map how we knew what other people meant be decoding the order in which we understand words to create meaning.

Since then, I’ve worked as an ESL teacher in various non-English speaking languages across the world. Here, I had to learn the language of the region I was in (often having been placed in rural areas where no English is spoken) and teach English at the same time. These teaching experiences in particular made it apparent just how much English is intertwined with specific cultural structures or ideas. For example, I remember teaching English time vocabulary to my Year 6 class in Thailand. I first had to show them that we split the day into two sets of 12 hours, compared to the 4 sets of 6 hours they use in Thai. Then, I had to show them the arbitrary markers we use to distinguish between morning, afternoon, evening, and night 9 (which in itself led to a 2 hour debate in the teachers lounge, because when exactly does evening turn into night?). Finally, I had to try and install the absolutely bizarre shift from saying in the morning, in the afternoon, and in the evening to saying at night. This week’s topic was thus really fascinating to me, and I absolutely enjoyed the videos and readings for the week. I did some additional digging as well, and further interesting papers on this topic can be found in the reading list at the end of this blog.

Annotations

I got about this far in annotating this video before realising the dealine for submission was 9am my time, not 9pm, and I stopped… But hopefully there are still some interesting points in there for people to enjoy!

| Time Stamp | Comment |

| 00:45 | I love that quote “”combining a finite set of words into an infinite set of new meanings”” – The exercise John Green does with book covers at the beginning of this video is a really fun way to put this idea into practice (video link https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=i_4bQpjB_pY). However, in the context of text and technology, we are seeing an increase in neologisms that are morphological deviations of words we already have to describe and identify their new digital counterparts. So perhaps it is a bit of a misnomer to think that we have a finite set of words |

| 00:50 | These tones, hisses, and puffs are really well mapped using the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA). The IPA is a set of symbols that linguists use to describe the sounds of spoken languages, and can be seen as a map of sounds available to a human. You can explore the chart on the website here https://www.ipachart.com/ |

| 01:01 | A more detailed description of the actual process of how sound waves become things we hear provided by TED-Ed here https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LkGOGzpbrCk |

| 01:07 | A great reading to expand insight into this is Evans, V. (2012). Cognitive linguistics. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Cognitive Science, 3(2), 129-141. |

| 02:33 | When I was working as an ESL teacher in Thailand, we had to a lesson that taught students how to correctly use the words “before” and “after” to show event sequences. It seemed simple enough, but in English you can use these interchangeable depending on emphasis. For example: “Before I went to bed, I did my homework” and “I went to bed, after I did my homework” or even “After I did my homework, I went to bed”. I noticed that my students were really struggling with this, and spoke to a few of my Thai co-teachers who explained that in Thai, you don’t have markers for before and after (use of tenses is very limited in Thai as is). Instead, you will always just say the events in the order that they happened. The placement of a statement within a sentence thus shows order of events, rather than linguistic markers of time relations. |

| 03:06 | Verb gendering is fascinating, and so diverse in languages! When I speak German, all nouns are gendered and have matching verb conjugation. In English, only specific objects are gendered (such as ships being “she”). In Thai, you use gender markers at the end of your sentence to indicate your own gender, as well as to indicate politeness and respect. So, as a female, I use the marker “ka” at the end of a sentence if speaking politely, but no specific nouns in the language are gendered at all. |

| 03:58 | This would make huge changes to the way news media worked in English, if we had markers for the sources of information! There are lots of other cool features that languages have that English does not, and Tom Scott outlines 5 of them in this great video https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QYlVJlmjLEc |

| 04:36 | An interesting anecdote on number words in the context of text and technologies. In Thai, the word for number 5 is pronounced “ha”, so in text speech, which laughing, instead of typing “haha” or “lol” they will type “5555” because it has the same phonetic sound as laughter! |

| 04:41 | Colour concepts across languages is one of my favourite topics. Here are three great resources for further insight into the topic if you’re curious. 1. The surprising pattern behind color names around the world (video https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gMqZR3pqMjg). 2. All The Colours, Including Grue: How Languages See Colours Differently (video https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2TtnD4jmCDQ). 3. Culture, language and thought: Field studies on colour concepts (journal article Groh, A. (2016). Culture, language and thought: Field studies on colour concepts.¬†Journal of Cognition and Culture, 16(1-2), 83-106. doi:10.1163/15685373-12342169) |

| 05:32 | This concept – the range of descriptive variations for a word – has been a central fascination of mine since discovering that people who speak other languages may have more words for something than we have as English speakers. I always wonder whether this is a difference in observations of the word, or whether this is a difference in needing to describe something many different ways. For example, Xhosa speaks in South Africa would have very little need for different word variations to describe snow, but Inuktitut speakers in the Canadian Arctic may well have functional use for describing all the different types of snow. |

| 05:39 | This concept – the range of descriptive variations for a word – has been a central fascination of mine since discovering that people who speak other languages may have more words for something than we have as English speakers. I always wonder whether this is a difference in observations of the word, or whether this is a difference in needing to describe something many different ways. For example, Xhosa speaks in South Africa would have very little need for different word variations to describe snow, but Inuktitut speakers in the Canadian Arctic may well have functional use for describing all the different types of snow. |

| 06:35 | Noam Chomsky (a hero amongst men) has some really interesting notions on how language and thought relate in this recorded interview https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KEmpRtj34xg |

| 07:54 | If looking at language evolutionarily, especially in relation to survival, the idea that all speakers are equally observant of all features of the world seems unlikely. It may be more probable to consider that language developed in relationship to things that needed to be given attention in any given society (i.e. weather, threats to life, options for food and shelter) and that these became remnants that were woven into the evolution of the languages we speak today, and account for some of the variations we see in the vocabulary of different languages. Further interesting ideas relating to the topic of awareness can be found in Konderak, P. (2016). Between language and consciousness: Linguistic qualia, awareness, and cognitive models. Studies in Logic, Grammar and Rhetoric, 48(1), 285-302. doi:10.1515/slgr-2016-0068 |

| 08:24 | Some people who have offered ideas on this can be found on the Stanford Encyclopaedia of Philosophy. Here is the link for the search term ‘language’ (website link https://plato.stanford.edu/search/searcher.py?query=language). One of the biggest thinkers with the limits and problems of language was the philosopher Wittgenstein which the School of Life covers quite nicely here (video link https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pQ33gAyhg2c) |

| 08:44 | Some other lovely quotes include: “The individual’s whole experience is built upon the plan of his language” – Henri Delacroix; “Language is a city to the building of which every human being brought a stone” – Ralph Waldo Emerson; “If we spoke a different language, we would perceive a somewhat different world.” – Ludwig Wittgenstein; “If you talk to a man in a language he understands, that goes to his head. If you talk to him in his own language, that goes to his heart.” – Nelson Mandela; “One language sets you in a corridor for life. Two languages open every door along the way.” – Frank Smith; “The limits of my language are the limits of my world.” – Ludwig Wittgenstein |

| 34:25:00 | PBS Idea Channel did a great video essay on this called “”Is Math a Feature of the Universe or a Feature of Human Creation?”” (video link https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TbNymweHW4E) |

| 35:55:00 | I am a huge fan of base 12! Numberphile did this great video on it https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U6xJfP7-HCc |

Recommended Reading List

Barner, D., Inagaki, S., & Li, P. (2009). Language, thought, and real nouns. Cognition, 111(3), 329-344. doi:10.1016/j.cognition.2009.02.008

Bruni, E., Tran, N. K., & Baroni, M. (2014). Multimodal distributional semantics. Journal of Artificial Intelligence Research, 49, 1-47. doi:10.1613/jair.4135

Bylund, E., & Athanasopoulos, P. (2014). Language and thought in a multilingual context: The case of IsiXhosa. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 17(2), 431-441. doi:10.1017/S1366728913000503

Evans, V. (2012). Cognitive linguistics. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Cognitive Science, 3(2), 129-141. doi:10.1002/wcs.1163

Fedorenko, E., & Varley, R. (2016). Language and thought are not the same thing: Evidence from neuroimaging and neurological patients: Language versus thought. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1369(1), 132-153. doi:10.1111/nyas.13046

Groh, A. (2016). Culture, language and thought: Field studies on colour concepts. Journal of Cognition and Culture, 16(1-2), 83-106. doi:10.1163/15685373-12342169

Konderak, P. (2016). Between language and consciousness: Linguistic qualia, awareness, and cognitive models. Studies in Logic, Grammar and Rhetoric, 48(1), 285-302. doi:10.1515/slgr-2016-0068

Lupyan, G. (2016). The centrality of language in human cognition. Language Learning, 66(3), 516-553. doi:10.1111/lang.12155

李彦佳. (2011). The innate relationship between language and thought. 科技风, (22), 211.

Rebecca Hydamacka

May 24, 2020 — 9:28 pm

Hi Jamie!

I am envious of multilingual speakers, I struggled with a second language, French, once I hit the complexities of verb conjugation in grade 11. I thoroughly enjoyed reading your annotations. A few of your notes connected with me and had me thinking:

0:45 “combining a finite set of words into an infinite set of new meanings” is a great quote. I do agree that it may not be a finite set as we are constantly adding new words and maybe not so great words such as “meh.” The best part of this quote is the idea that words can be combined in so many or infinite ways. I like the idea of being able to play with words and visualize something like a lego set. Language goes beyond the words to include subtle gestures such as a furrowed brow or shoulder shrug or a tone of voice.

And I absolutely love the way John Green put the book titles together! Thanks for this example.

5:32 “This concept – the range of descriptive variations for a word . . . ” It does stand to reason the someone in South Africa would need less words to describe something they do not experience. I wondered if there is less words for one noun, would there be more adjective used? Or if there are many words to describe one thing then less descriptive adjectives? Or perhaps the importance of an item is what might demand more words to describe it in detail?

Jamie Ashton

May 24, 2020 — 10:11 pm

Hi Rebecca,

I really like your thoughts on adjectives! Perhaps the range of words we have in a single language are the result of adjectives used. I.e. before the Inuktitut language had 13 (random number used) words for snow, they had one. But then people described snow differently, and over time these descriptions became neologisms instead because there was value to having distinctions for snow types. In that sense, I totally agree that the importance of an item probably correlates with the need/demand to describe it in more detail. I shall ponder it further, but I am intrigued.

Alanna Carmichael

May 26, 2020 — 11:14 pm

Hi Jamie,

So interesting to read about your experiences teaching English in Thailand. I hadn’t considered the fact that we transition from “in the” morning/afternoon/evening to “at” night rather arbitrarily, as you pointed out. It is fascinating to me how many subtle nuances there are in the English language (and any language, for that matter) that determine whether someone is speaking/writing with “correct” or “incorrect” grammar. I can only imagine the challenges you face with trying to learn the local language while simultaneously teaching English. I’m sure you sometimes feel that you are learning just as much as you are teaching!

Thanks for sharing your thoughts and experiences.

Jamie Ashton

May 26, 2020 — 11:21 pm

Hi Alanna,

Yeah absolutely! I found that learning whilst teaching helped in a number of ways. It really gives me insight into the challenge of learning a new language, which both gave me patience with my students and ideas on how to teach them better. Everytime I learned how to say something in Thai, I would notice how the syntax and logic of the language was different to English, which I could then reverse engineer to help English make more sense to my class. Here’s to enthusiastically embracing informal lifelong learning 🙂

SHAWNLAU

June 3, 2020 — 11:09 am

Hi Jamie,

So interesting about your early life and the languages you speak, can you still speak 6 languages? And which 6? Also, what is your perspective on what’s happening in the U.S. currently, living in a country with official multi-lingualism?

Your syntax tree is pretty amazing, I took a few intro linguistics classes during my undergrad. I really enjoyed transcribing phonetics.

Thanks for sharing your life and teaching experiences.

Shawn

Jamie Ashton

June 4, 2020 — 3:33 am

Hey Shawn,

I still carry 4 fluently, and have picked up some other ad hocs along the way due to living in different places where English wasn’t prominent at all. The fluent include English, Afrikaans, German, and Thai.

When you are asking about the US, what are you referring to? Just the rising idea that cultural homogeneity is important?

Glad someone else enjoys the insanity of Linguistics work 😀

brian leavitt

July 19, 2020 — 12:34 pm

Hi Jamie,

I found your annotations about language and cultural context really interesting. I agree that cultural context alters and affects our language, and our language changes our very understanding of the world and what we think as important.

I find colours really interesting, for example. We would probably all agree on what the colours are, but why is that? We were likely all raised being told repeatedly what blue and red are, being shown examples at pretty specific points on the colour spectrum. What if we had instead been shown examples that focused on areas on the colour spectrum that are in between the colours we consider as being ‘key’? How would that change the way we view the world?

I also find this interesting being colour blind, as I always wonder how others see the world. I don’t see much difference between blue and purple, or some shades of red/green/brown. The words are mostly meaningless to me. I usually just guess which one it is, and only know different if someone tells me. Does this change anything fundamental about how I understand the world?

Jamie Ashton

August 5, 2020 — 5:18 am

Hey Brian,

I’m glad you found it interesting. Colour relativity is a massive philosophical and psychological problem people have been grappling with for ages! It’s a fascinating question, whether your colour blindness changes how to understand the world. Have you ever discussed it with close friends or family who do see the colours you don’t? Anything that has arisen? I’d be curious to hear more.