During my undergraduate in religious studies, we often came across the topic of what happens when oral stories become codified into text. Christianity, Islam, and Buddhism, for example, all functioned as oral traditions before someone decided to write them down into textual canons that became the scripture we have today. Many questions arose from this: what changed when these stories were carried and shared orally between followers of Christ and Buddha in the 50+ years after they died before they got written down (suspending all argument of whether these figures did historically exist or not to focus more on the modality of oral vs text)? Who was responsible for remembering them? How did they decide which person would dictate a story to be textually recorded? And who decided how they were written down or what sections were important enough to be written in an age where paper and ink was expensive and the skill to write was not common? What does this mean for how to interpret and follow the texts that exist today?

These questions all stand before we even begin looking at the texts that then got rewritten and translated over the following centuries, being moulded by political shifts and new cultural values. If we questioned the “integrity” of text when being codified from oral traditions, the integrity of text when being changed to further/altered/translated/different texts should be questioned as well. In Buddhism, for example, the texts were written on banana leaves and it was the responsibility of studying monks in monasteries to copy and rewrite old texts onto new banana leaves. We can assume that they treated this task with reverence and attention to detail, but we cannot be certain. This indicates that text, which is something we think of as so reliable to hold truth, could actually be a lot more transient that we like to think.

My current favourite discussion regarding shifts from oral to text comes from observations of memory discussed by Illich and Sanders in The Alphabetization of the Popular Mind (1998). In a discussion about the etymology of memory and how the notion of memory was only constructed once speech was able to be codified into textual formats, Illich and Sanders identify how the technologies of practice shifted in a case study of how epic poems are learned and sung. Tracking classical texts that were previously oral technologies and referencing Lord’s study of Syrian bards, Illich and Sanders (1998) exemplified how the production of sung folklore changed once it was committed to a textual technology. These long narrative tales were traditionally learned through a system of apprenticeship during which aspiring guslar would listen to the bards performing until they had internalized the tales. When they later performed the songs themselves they would not replicate the stories they had heard, but instead reconstruct them and produce an entirely new piece whilst still reproducing the central crux of the tale. At some point, however, these songs became textually documented and, thereafter, bards were expected to perfectly recite the stories to mirror the textual documentation of the lyrics and lore. There was thus a shift in both the technologies used as well as in the practices of memory. Where previously natural and spontaneous oral technologies that rested on spontaneous thought had been used for song there was now precise textual technologies that demand techniques, exercises, and reproduction for song.

Voice to Text Activity

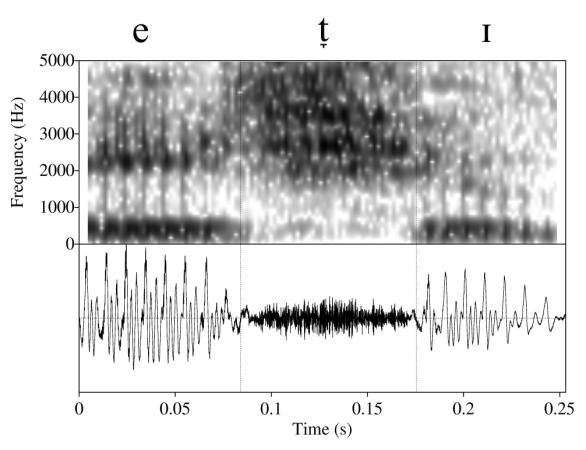

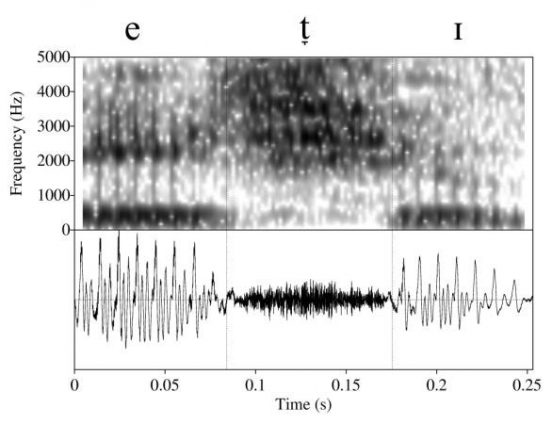

There are many other ways oral traditions can become text. In Linguistics, we speak into a microphone to record not our words but the sound waves we produce in order to analyse them. These spectrograms are beautiful yet haunting recordings of the sounds we make, and give us a whole different insight into the links between words, texts, and technologies.

There is a conversation in linguistics research which has long fascinated mean. It’s concerns whether gesture preceded speech or speech preceded Gesture in order to look at the evolution of language to the systems that we have today. The idea that just who preceded language is probably the most compelling out of the two for me karma since it would make sense that within proximity we wouldn’t want to gesture and indicate things to one another when we left and communities. However, what’s the concern that without a vocalisation or some sort of guttural indication there would be many gestures which could be overlooked if humans were not already making eye contact with or observing one another. This means that there is the possibility that instead of gesture preceding language language actually preceded gesture. The stew makes little sense so when considering back without an indication between sound and object language would seem very abstract and not be able to develop easily without people having a shared understanding of the object that they were trying to indicate or me. So perhaps it is most compelling to look at gesture and language as things that developed together rather than things that developed causally one from the other. The idea that one word gesture to something and make a noise karma even the concept of mimicking animals and the sounds that they made an order to refer to something one has seen or interacted with that day probably makes the most sense. It is a difficult thing to question and determine though especially since we know that language with certainty preceded text the idea of trying to establish whether gesture or language caused one another is quite complicated. I guess the Small Part of Me also wonders if there is any sort of meeting that can be cleaned if we establish whether gestural language came first. Do you think that there is value in determining which one originated first? Do you think that gesture all language play dab in developing text in the sense that one was possibly more important than the other? Do you possibly also think that text as an evolutionary aspects of language existed long before the letters that we recognise today to? The readings this week discussed small clay pieces and markings that were used specifically to count but are there other ways in which art functioned as text long before text existed? Cave paintings could have possibly worked as documentation of big events or occurrences or interactions that happened in society before text exhausted. Welsh questions of how language related to text or important questions of how we integrate gesture into text or interesting as well. Emojis and punctuation count as textural jesters? And how does the history of language gesture and text influence the textural systems and communication that we have in technology today? I always find it really difficult to differentiate between the importance of history and understanding where we are now and simply looking at where we are now is a unique moment. Ignoring the trajectory so to speak in favour of understanding the present without causality and without relationship to things that are past. Has been a significant Gramble now which I guess happens when you’re essentially speaking to yourself but it is an interesting one and I’m curious to see and hear what other people think around this topic as well.

The text deviates from conventions of written English in a number of ways. The most prominent to me is the irregular use and placement of punctuation, as this was something exceptionally challenging for me to remember to integrate into my speaking. An error that only occurred once was it reading my punctuation commands as words, writing “karma” instead of placing a comma in the sentence. At times it also capitalised words that do not require capitalisation, such as the word ‘gesture’ in the second sentence or it writing “the Small Part of Me” rather than “a small part of me”. That said, most of the text correctly reflects the words I was saying with only a small handful of mistakes I think of as ‘errors of mishearing’. These mistakes are a case of the written word not mirroring the spoken one, and the sentence losing meaning because of it, possibly due to the machine not being able to process my accent or the word I said in relation to other words surrounding it. Examples of this include ‘me’ being written as “mean”, ‘gesture’ being written as “just who” or “jesters”, ‘meaning’ being written as “meeting” , ‘ramble’ being written as “Gramble”, ‘which’ being written as “Welsch”, ‘would’ being written as “word”, and ‘existed’ being written as “exhausted”. Once or twice “are” and “or” were switched. Finally, there were also a few mis-written phrases such as ‘gesture and language played a role’ being written as “gesture all language play dab in”, and ‘within our communities’ as “when we left and communities”.

I personally would have enjoyed doing a scripted story for this exercise, as it would have allowed me a more intricate analysis of what differed between my original speech and what Speechnotes recorded. When looking at the produced text afterwards, I struggled to remember what I originally had said in places where the text is unclear. There are also sentences that are not syntactically ideal, with word orders and sentence constructions feeling odd when reading them in written form. Having a scripted story would have made it easier to dictate into the app, reminding me about when to give commands for punctuation. If a script was allowed, though, then this may have been less of an activity where we look at speech to text, and more of an activity where we look at text to text mediated through speech. This point brings us directly to the difference between speech and text (or oral storytelling and written storytelling).

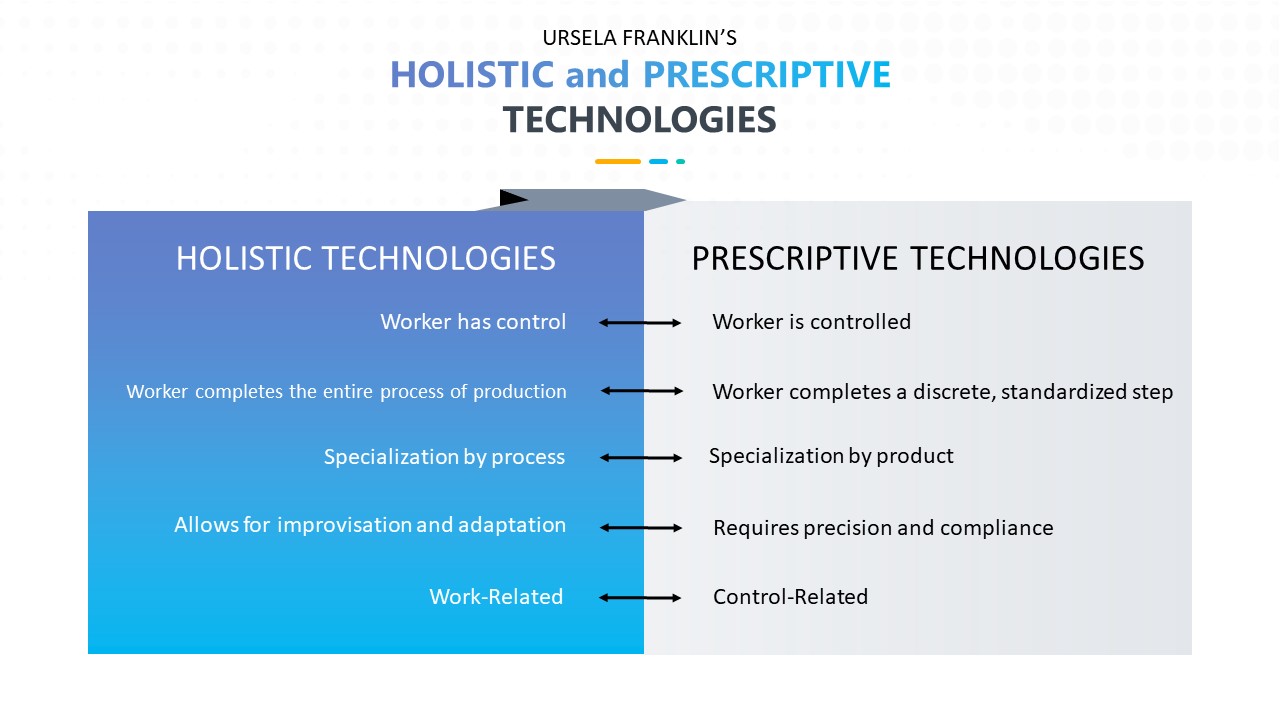

In oral storytelling, relationships between sentences/words/meanings occur organically through the use of pauses, tones, and emphasis. Furthermore, facial features and gestures can add further insight and depth to what is being said. All of these features are lacking in written text, and need to be constructed more intentionally through adherence to rules about sentence structure, paragraphs, and punctuation instead. If using terms put coined by Ursela Franklin (1999), I would classify written storytelling as a prescriptive technology and oral storytelling as a holistic one.

Written storytelling requires the author to adhere to the standards of text for others to be able to follow the story and understand the meaning of it. It requires a series of steps in which you have an idea and formalise it using the conventions of written text so as to share it with others. The job of the writer is to be precise and compliant with standards of writing so that it can be received by others. Even in cases where the rules of language are bent, such as in poetry, it still assumes the reader will know the conventions being broken to understand the meaning of the text. Oral storytelling does not carry such requirements. The idea can be shifted and moulded and shared by a speaker without adherence to rules of language, since tone and gesture and emphasis will all aid in sharing meaning. Think about reported speech as an example. In written storytelling, there are procedures for showing when you are reporting speech, with he said/she said precursors and new lines or quotation marks to show speech. In oral storytelling, you can simply change your voice to indicate that you are reporting speech without further framing being required at all. So, oral storytelling seems like something where the speaker retains control of the language, where as in written storytelling the writer has to generally conform to (i.e. be more controlled by) textual language. This is really poignant for me, and made me nod my head along with a lot of the readings we were set this week.

Thoughts Whilst Reading

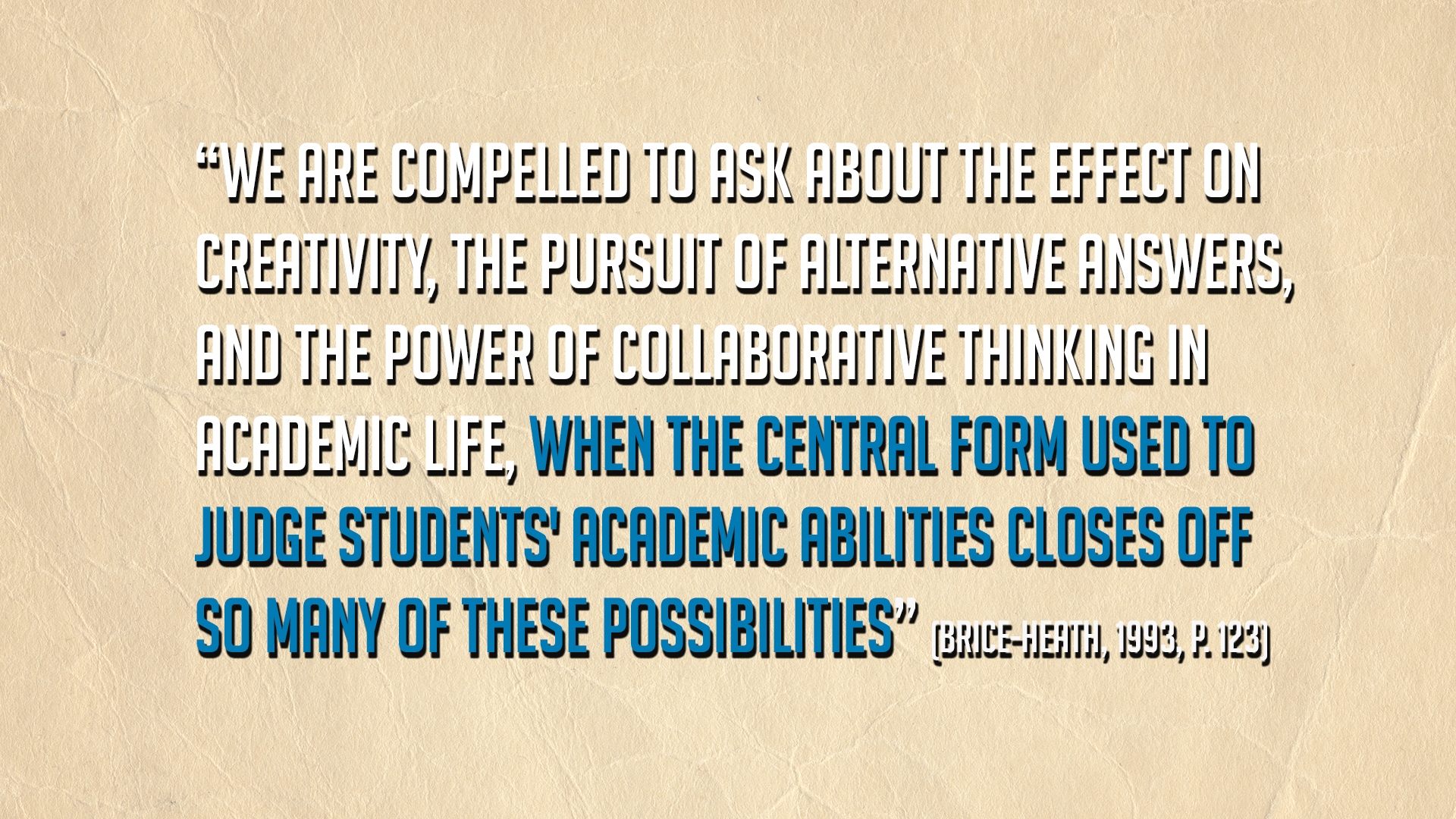

In the first few pages of Chapter 1 from The Orality of Knowledge (2002), there was a discussion around how written language could well be considered limited in comparison to some of our other methods of communication. The richness of that paper aside, the quote below from Brice-Heath (1993) in her paper discussing the essay as the legacy of the epigram – and what has been lost along the way – effectively outlines the tension of using written storytelling as our primary (and often only) way for producing and testing knowledge in academic spaces… and critiques it in one fell swoop as well.

Whilst reading the Origins and Forms of Writing (2009) paper, I was reminded of living in China and wanting to use google translate to decipher mandarin text in the world around me. Sometimes the camera based interpretations were not clear and I decided it would be good to simply copy the characters I was seeing into the tactile writing input. Little did I know that there is an organised sequence to producing the lines in Chinese characters, and if I did not follow the grammatical order (for want of a better term) of line drawing for a character then google would not translate it for me! Whilst we have prescriptive standards in English on ‘best practice’ for writing a letter, Google is much better at interpreting characters even if they are not drawn in the expected order.

Lastly, when reading the CBC article about Kobe, the indigenous language app, I remembered reading about Kelly Fraser last year. She has been translating pop songs into Inuktitut, and in the video below speaks about the challenges of translating modern pop vocabulary into a language that is both old and closely to the earth. Her fame also stems from her uploading her performances of translated pop onto Youtube and Soundcloud, so it is another great find for the text and technology melting pot we are creating together in this course.

Recommended Reading List

Bell, C. (1988). Ritualization of texts and textualization of ritual in the codification of taoist liturgy. History of Religions, 27(4), 366-392. doi:10.1086/463128

Brice-Heath, Shirley (1993). Re-thinking the sense of the past: The essay as legacy of the epigram. In Lee Odell (ed), Theory and Practice in the Teaching of Writing: Rethinking the Discipline (pp. 105-131). Illinois: Southern Illinois University Press

Bula, D. (2017). A complete edition of an oral tradition: Text selection practices in the history of publishing latvian folk songs. Folklore, 128(1), 37-56. doi:10.1080/0015587X.2016.1235423

Clivaz, C., & Schulthess, S. (2015). On the source and rewriting of 1 corinthians 2.9 in christian, jewish and islamic traditions (1 Clem34.8;GosJud47.10–13; aḥadīth qudsī). New Testament Studies, 61(2), 183-200. doi:10.1017/S0028688514000307

Franklin, U.M. (1999). The Massy Lecture Series I. In Franklin, U.M. (Ed.), The Real World of Technology (pp.20-45 ). Canada, Toronto: House of Anansi Press.

Fröhlich, M., Sievers, C., Townsend, S. W., Gruber, T., & Schaik, C. P. (2019). Multimodal communication and language origins: Integrating gestures and vocalizations. Biological Reviews, 94(5), 1809-1829. doi:10.1111/brv.12535

Hurtado, L. W. (2014). Oral fixation and new testament studies? ‘Orality’, ‘Performance’ and reading texts in early christianity. New Testament Studies, 60(3), 321-340. doi:10.1017/S0028688514000058

Illich, I. & Sanders, B. (1998). Memory. In Illich, I. & Sanders, B. (Eds.), ABC: Alphabetization of the Popular Mind (pp. 14-28). USA, New York: Vintage Books.

Joskovich, E. (2019). Relying on words and letters: Scripture recitation in the japanese rinzai tradition. Japanese Journal of Religious Studies, 46(1), 53-78. doi:10.18874/jjrs.46.1.2019.53-78

Kamesar, A. (2005). Hilary of poitiers, judeo-christianity, and the origins of the LXX: A translation of tractatus super psalmos 2.2-3 with introduction and commentary. Vigiliae Christianae, 59(3), 264-285. doi:10.1163/1570072054640513

Kendon, A., & Kendon, A. (2017). Reflections on the “gesture-first” hypothesis of language origins. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 24(1), 163-170. doi:10.3758/s13423-016-1117-3

Ong, Walter, & J. Taylor (2002). Chapter 1. In Orality and literacy: The technologizing of the word (pp. 5- 15). New York/London: Routledge.

Prieur, J., Barbu, S., Blois‐Heulin, C., & Lemasson, A. (2019). The origins of gestures and language: History, current advances and proposed theories. Biological Reviews, 95(3), 531-554. doi:10.1111/brv.12576

Schmandt-Besserat, D. (2009). “Origins and Forms of Writing.” In Bazerman, C. (Ed.), Handbook of research on writing: History, society, school, individual, text (pp. 7- 26). New York, NY: Routledge.

Taylor, M. (2015). How to do things with sanskrit: Speech act theory and the oral performance of sacred texts. Numen, 62(5/6), 519-537. doi:10.1163/15685276-12341390

Zhiru, S. (2010). Scriptural authority: A buddhist perspective. Buddhist-Christian Studies, 30(1), 85-105. doi:10.1353/bcs.2010.0009

emma pindera

June 1, 2020 — 4:20 am

Wow! What a thorough analysis, thank you for sharing your reading list and also giving me something to think about regarding the oral traditions of religions. It is interesting that most religions use their holy texts as The Word, yet you’re right before it was written down it was oral story-telling.

Oral-storytelling always makes me think of the childhood game broken telephone, where you have to remember exactly what the person beside you whispered without them repeating it. It is a fun game to play, but it does show the inaccuracy of oral story-telling.

When I went on a trip to Greece, they showed the theaters that would be used for news reports, plays, and religious stories. These same spaces and stories would be told as if they were the same. The stories of Zeus mixed in with the stories of politics. It makes me wonder the accuracy of it all, or whether at that time, it was meant to be for entertaining purposes rather than informing.

Jamie Ashton

June 2, 2020 — 12:47 am

Hey Emma,

Sometimes I guess it is not a question of accuracy but of meaning. Judaism, for example, takes their texts not as literal but as philosophical; things that need to be questioned, investigated, and interpreted so that true insight can be achieved. Your comment is interesting though, because it shows some perspectives that have only really become possible through the rise of modernity.

Before the rise of modernity through the empirical sciences in the 16th century, there was a centrally held societal and political idea that knowledge was accessible and that the world is structured in a way that is both real and able to be discovered and accessed by individuals. Furthermore, all knowledge had theological underpinnings in the sense that it was conceived that the world was created by God, knowledge and language were God-given and that the nature of an individual was chosen by god. With the rise of new sciences however, there were implicit consequences for these religious knowledge foundations and other aspects of society. Firstly, values for social, political and economic hierarchies that were previously drawn from tradition and/or theology shift and are reconsidered and openly negotiated from a more secular framework (i.e. governments). Secondly, new conceptions of identity that are not drawn from societal placement of God given nature arise and individuals are now able to either create their own identity or be created through systems of socialisation. Thirdly, art is both commodified and becomes a source of societal reflection or artistic freedom rather than being public entertainment or a symbol of societal power. Fourthly, language is considered relational and subjective to the individual rather than being a God-given symbolic representation of an inherent order and truth. Lastly, knowledge is no longer seated in theology and tradition but is rather a rapidly fluctuating influence being developed through the natural sciences and humanities. This began a series of philosophical conversations that attempt to resolve which epistemological structures and influences should guide ethics, social structures, political systems, individual rights and identities as well as knowledge and truth.

So, the idea that religion is separated from politics, or art, or truth, has only really happened post-Enlightenment with the rise of secularism and rationality. Even the idea that entertainment and informing are separate is only something that exists now; at the time, entertainment and information were the same thing 🙂 Concepts of truth as not defined by religion would never have even been considered, and neither would be reports or plays! Interesting, hey

Fred Rush has fantastic writing on this, if you’re interested!

Rush, Fred. 2004. “Conceptual Foundations of Early Critical Theory.” In The Cambridge Companion to Critical Theory, 6-39. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rush, Fred. 2004. “Introduction.” In The Cambridge Companion to Critical Theory, edited by Fred Rush, 1-5. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Emily

June 1, 2020 — 11:46 am

Hey Jamie,

You pointed out some interesting connections throughout your post on religion, songs as living historical documentation and between speech-to-text/ translation apps, which reinforce the point that writing can both distort and misrepresent oral language. The idea that Western society holds writing as more valuable or true than speech has changed the way we think and learn. Just as it you mentioned, the way songs were performed changed due to the ability to textually record the lyrics which caused a greater emphasis to be placed on memorization rather than interpretation and creativity. This can also lead to narrowing the ideal of perfection and reducing risk-taking in learning and verbal participation. Therefore, the use of writing, and technology to produce writing, has shifted the emphasis from learning as internalizing and making-sense of concepts in a way that one will embody, to masking performance with a piece of paper or computer screen.

In my teaching practice, I see this as students preference rather not give presentations in front of the class because they are uncomfortable in open discussions with no time to prepare and write down their thoughts. At the ministry level, it is also recorded by the absence of speaking and debate from final exams. What you know in those cases, is what you can write down and document. This changes the emphasis of teaching to accommodate very specific learning objectives for answer questions and writing essays, rather than creative expression and inter-disciplinary multimodal learning.

Also, I hadn’t heard of Kelly Fraser before, but I will have to check out more of her work. Do you know if she translates the songs orally or also writes them in syllabics? I wonder, since this is a new system of written language, how the Inuit people perceive it affects their oral history and language as a whole? Side note, my favourite band from Nunavut is ‘The Jerry Cans’ and they sing in both English and Inuktitut.

Jamie Ashton

June 2, 2020 — 1:29 am

Hey Emily,

I love that you tied that back to classrooms and learning – I completely agree! Students so often only see themselves as capable of showing knowledge but writing it… I hadn’t made that connection before. Very specific learning objectives indeed.

I don’t know how Kelly Fraser translates, but it is a great question. Maybe one of us could email her and ask? Will be checking out The Jerry Cans in the meantime 😀

tyler graham

July 2, 2020 — 3:01 pm

By god you go above and beyond! Thoroughly impressive your analysis of all this. I had a fun time with your voice to text – due in large part to the errors. And again, you went totally above and beyond in highlighting every single one of them. And as for which came first, gesture or speech, I’m with you in saying they developed simultaneously – but I suspect that gesture began as more effectual, before speech overtook it. But that’s just a guess!

Jamie Ashton

July 2, 2020 — 11:43 pm

Hey Tyler,

A little indulgence always makes things more enjoyable 😀 The errors do make things interesting – almost poetic some might say.

I like your ideas on speech/gesture development! Will ponder ever further and see if I ever reach a conclusion I feel certain in.

Til soon!