We know dictionaries don’t contain all the words, even the ever evolving online ones. Language is wonderfully elastic, able to be manipulated not just by the authorities but by you, too. In an increasingly digital world, you may have forgotten the mysterious power of your own handwriting, and that the glowing text on your screens started out somewhere as scratches on stone, attempts by one human to communicate with another. We’re making this all up, friends. All of it. – Sarah Urist Green, You are an Artist (2020)

First things first, did anyone else struggle with the extreme melodrama of the required podcast this week? I just giggled at the seriousness of the tone and background music and AI like voice throughout the entire thing. It was informative though, and with that digression out the way, let us move on to the task for this week!

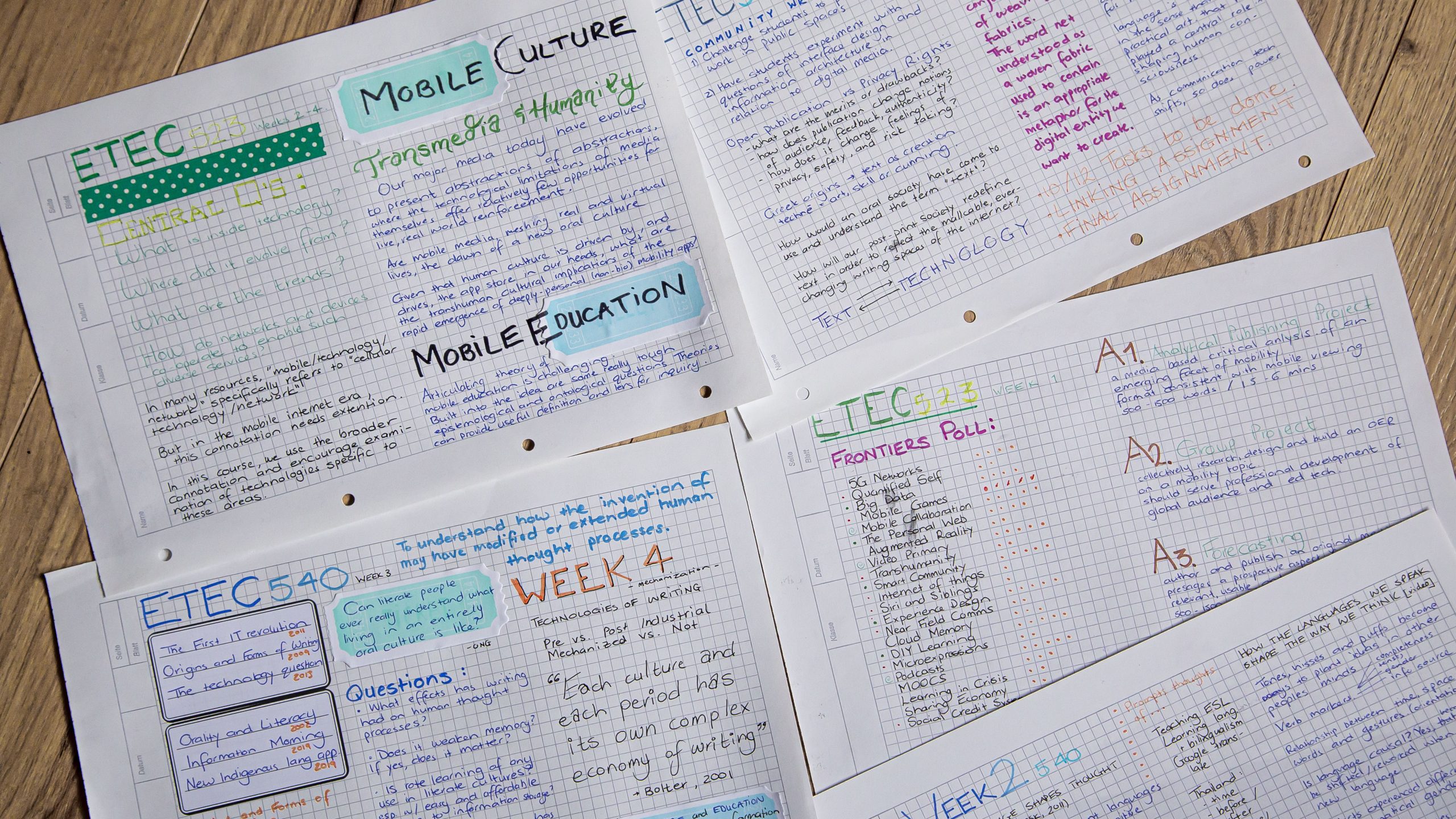

Whilst I didn’t do the handwriting section of this task, I wanted to engage with the questions a little as I do spend a lot of my time manually writing by hand. My MET notes in particular have become somewhat of a sacred activity, in which I mindfully consider my new knowledge and carefully construct it on the page. Blending text and paper and placement to come up with something halfway between notes and mindmaps and infographics. I wish I had my usual MET visual diary to share with you, but you can see some examples of my ad hoc solutions in the meantime.

Using different pens and media makes my handwriting playful, but it also helps me consciously decide how to internalize and display content. It’s practically a warped form of self-imposed project based learning. Due to all the conscious construction however, mistakes are a lot less rare and plotting my writing styles happens before ink seeps into dead trees. Don’t get me wrong, my laptop is my best friend and I am a prolific typer. If it weren’t for mechanised writing you would not have me blogging or probably even writing essays. I thus love mechanized and handwritten type equally, as they both have very different strengths and allow me to achieve very different writing tasks with very different intentions.

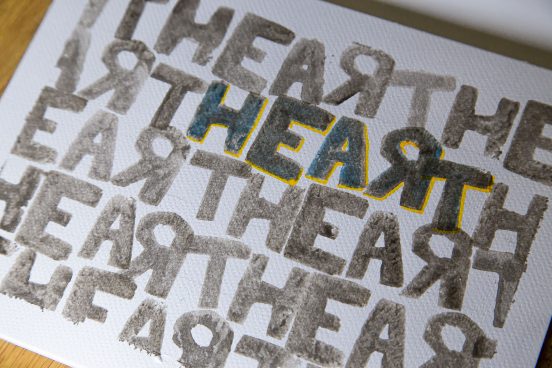

So, on to potato stamps! I was so excited to do this again. The last time I used potato stamps was when I was in Year 12 doing my final art projects and I made symbols from the rorschach test with potatos and used them to print huge portraits of people (it was a fun investigation of theories of id, ego, and superego that I thought was very profound at the time)! I went a little overboard and did a whole page of the word rather than just two copies, but this was also because there was interesting play in the word I selected that I wanted to highlight as part of this task.

Potato Printing Reflection

The word I chose was “heart” because when printed side by side you can find at least 4 other words in it (let me know what other words you can find in the comments). The cutting of shapes itself was a quick 10 minute process, and printing the words took around 10 minutes too. But this, of course, was not the extent of time that it took to create the stamp. I had to go to the shop to get potatos as the ones I had in the cupboard had all sprouted eyes. Then I had to research whether using them freshly cut or halving them and letting them dry was better for printing. Then I had to spend 2 days trying to find the time in my schedule to actually cut and use them. This was probably the most challenging part of the process for me in my current context, actually finding a moment to sit down and make the stamps.

I did find the process of making and using them very calming though. A moment of horror arose when I realised that the letter ‘R’ would only print backwards, and that I should have made it the mirror image for it to print “properly”. Rather than fixing it though, I decided to embrace its bespoke quirks and let it shine. Much to my relief, all the other letters were symmetrical enough to still represent themselves, even when technically printed backwards. I used watercolour paint to make the prints, which was quick to use and dry and made the whole process very efficient.

Having gone through this process, the mechanisation of printing is certainly something I am thankful for. Whilst it is a fun activity to do an exercise like this, I cannot imagine needing to do any of my daily text based work with such manual labour required. I send probably ±20 emails a day, spend all day communicating with my team on Slack, create training exercises for the internal team, write feedback on assignments, copyedit texts, put together schedules, run social media accounts with captions, and write messages to family and friends. None of this would be vaguely possible if mechanisation of text didn’t exist, and even if I decided to handwrite/print all my correspondence, it wouldn’t be as neat or readable or easy to respond to. Mechanization thus enables clean, quick, efficient, repeatable production of text. Digital mechanization enables the creation of letters that can be formatted/resized/edited without effort, that can also be manipulated, changed, and shared in so many ways that hand printed text on realis paper cannot be. This also highlights the fact that mechanisation of printing is half the game here, and mechanisation of printing that becomes digital text that we share over networked internet platforms is a very important other half to reflect when thinking about the crossing threads of text and technology today.

This combo (mechanisation + technology + networked digital infrastructure) has played a huge part in shaping the society we have today on micro and macro levels. It certainly helps with the decentralisation of knowledge, and it is a tool that has been able to completely shift how society thinks and shares information. I find myself wondering what thinkers like Foucault or Heidegger would have to add to a conversation like this, and enjoying what writers like McQuail (2010) have said about print media (specifically newspapers in the quote below) and their effects on society.

It’s distinctiveness, compared with other forms of cultural communication, lies in its orientation to the individual reader and to reality, its utility and disposability, and its secularity and suitability for the needs of a new class: town-based business and professional people. It’s novelty consisted not in its technology or manner of distribution, but in its function for a distinct class in a changing and more liberal social-political climate. – McQuail (2010, p. 28)

Other good reads in the realm include Eisenstein’s (1978) discussion on how printing created a revolution in society by making it possible to write down and share laws and Febvre and Martin’s (1984) paper on printing becoming a form of commerce in and of itself. To close, I invite you to think about how your identity might be different if you didn’t have access to mechanised textual technologies. Do you think you would have been influenced by the same things you have been? Would you think of yourself in the same? Present yourself in the same way? Would you have the job you have, or be able to conduct the work you currently do? How much of who we are is related to the information we are able to share and receive due to mechanised textual technologies? I know I’d probably be a little different…

Video Library

Here are two great videos (one short, one long)

Recommended Reading List

Brice-Heath, Shirley (1993). Re-thinking the sense of the past: The essay as legacy of the epigram, pp. 105-131 in Theory and Practice in the Teaching of Writing: Rethinking the Discipline, Lee Odell (ed).

de Castell, S and Luke A: (1986) Defining Literacy in North American Schools: Socio Historical Conditions and Consequences in de Castell, Luke and Egan (eds) Literacy, Society and Schooling. Cambridge University Press.

Eisenstein, E. L. (1978). In the wake of the printing press. The Quarterly Journal of the Library of Congress, 35(3), 183-197.

Feather, J. (1984). The Commerce of Letters: The Study of the Eighteenth-Century Book Trade. Eighteenth-Century Studies, 17(4), 405-424. doi:10.2307/2738128

Haas, C. (1996;1995;). Writing technology: Studies on the materiality of literacy. Mahwah, N.J: L. Erlbaum Associates.

Lawler, P. A. (2014). Technology and mechanization today. Society, 51(6), 595-601. doi:http://dx.doi.org.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/10.1007/s12115-014-9831-9

McQuail, D. (2010). McQuail’s mass communication theory (6th ed.). London: SAGE.

Olson, David (1980/2006). On the Language and Authority of Textbooks. Journal of Communication. Volume 30, Issue 1, 1 March 1980, Pages 186–196, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.1980.tb01786.x

Powell, B. B. (2012). Writing: Theory and history of the technology of civilization. Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell.

Rogobete, S. E. (2015). The self, technology and the order of things: In dialogue with Heidegger, Ellul, Foucault and Taylor. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 183, 122-128. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.04.854

MargaretNash

June 5, 2020 — 11:05 am

Jamie – the thoroughness of your posts is amazing!! Part of me wants to make my posts better, but in all honesty I don’t think I could do what you do! I LOVE reading your posts and appreciate your links to other readings and videos. (Maybe it’s the fact that I am not a writer at the best of times, so I have a hard time getting my thoughts into a blog!!)

Back to your post … I love the backwards “R” – it adds a playfulness to the word! Here are my “heart” words:

– art

– tear

– hear

– heat

– rate

– eat (I’m a Foods teacher)

– the

I love thinking about words like this – and the fact that many of those words relates to the literal and figurative references to heart!

And I totally agree about the podcast – it took me a while to get past the eerie music and tone of voice.

As a non-writer, what do you find helps you to be motivated to write things down (either by hand or on a device)? Any tips or tricks to helping me enhance my blog posts would be appreciated!

Meg

Jamie Ashton

June 6, 2020 — 12:15 am

Hey Meg,

I think it’s all about finding your own style – getting to doing what YOU do in a way that makes you happy 🙂 Blogs are lovely, because they’re not confined to just writing. As you can see, my writing is littered with other media forms and that is part of what can make this both fun and a reflection of you (if you want to).

Glad the ‘R’ is being considered a success! I had a solid minute of sadness when I realised it, and sat on my floor wondering whether to start again! My wallowing brought me to the point where I realised quirkiness is part of life, and somewhere in the world a typographer designer probably spent hours coming up with a backwards ‘R’, so I should just embrace this as a strike of inspiration and run with it ????♀️

So many words oh my gosh! I’m never going to look at “Heart” the same way again! And indeed, they do link up and overlap a lot.

My major motivator is good communication and inspiring curiousity in others. It’s also a lot of that 80% planning, 20% execution approach. Where I don’t write my blog all in one go. At first it’s a mess of resources that I’ve found thrown under the headings (or main points) I want to address. Then I start writing the connections inbetween, refining and organising the content as I go. I also always try think not only about the information I want to share, but why I am sharing it. What made it interesting to me? What do I want other people to possibly realise or reflect on when reading it? And from there on, it’s all just play to see what works!

Dunno if any of that is helpful, but hey! It’s there now 😀

HelenRogan

June 6, 2020 — 1:26 pm

Hi Jamie,

Really enjoyed your post. I LOVE that you decided to keep the R backwards. I also didn’t realize I would have to carve the letters backwards, and ended up re-doing 3 of them…and wasting more potatoes. Fortunately I had some old ones I had forgotten about that would have ended up in organics anyways. But your decision to keep it like that makes your design unique!

I appreciated your comment:

“This also highlights the fact that mechanisation of printing is half the game here, and mechanisation of printing that becomes digital text that we share over networked internet platforms is a very important other half to reflect when thinking about the crossing threads of text and technology today.”

Much of my thinking on this task focussed on how new technologies allowed information to spread more quickly in the printing press era. However extending the timeframe to today demonstrates that text technologies continue to drive the advancement of knowledge. Just like greater access to print materials led to an intellectual revolution, greater access to information through digital technologies has led to a more informed society. It’s interesting to consider what the long-term consequences of this will be.

Rebecca Hydamacka

June 7, 2020 — 8:50 pm

Hi Jamie,

The very first word that leaped from the page was “HEARTH” (sorry I don’t know how to reverse the “R.” The hearth being much like the heart or the center of a home. And now I am seeing earth in this comment. I had also thought to get the most out of my letters initially but went off on a tangent as I am about to do now. Circling back to you notes, which look fantastic! I almost wish I had posted some of my 450 notes who’s only practicality is the kinesthetics. I cannot really read my own notes but feel compelling to write them. I have tried typing into a google doc but it is not the same as if is more difficult to circle back to bits and pieces.

We are definitely different because of technology. I don’t think I would be an educator today if I did not have access to online courses. I am also thankful that it allows my writing to be more legible. The printing press revolutionized access to text and increased literacy. What literacies are increasing now? I just helped a non-digital native access an online Safety training course and earlier helped him to create a Facebook account (I am also not a digital native). I wonder about how further advances in technology with impact society and the way we live.

VALERIEIRELAND

June 16, 2020 — 11:04 am

Jamie,

Three quick comments:

1) love the use of different colour and directions of your print. Captures a message so much more than a ‘standard piece’

2) thanks for the TEDed video. Haven’t seen that one before and I’ll be sure to keep it in my repertoire/brain library!

3) that podcast bugged me too, but because I have hearing difficulties and found the background music made it hard for me to hear the message. I really enjoyed the podcast, but it physically hurt my ears to listen to it with the background music and sound effects.

Thanks again for all your insights!

Valerie

Jamie Ashton

June 20, 2020 — 12:25 am

Hi Valerie!

Interesting to note that the podcast actually impacted your ability to receive the information. I think it’s something important to note in the new “textual technologies” of the digital age, that they possibly need to be shared in multiple formats to assure accessibility for all.

Thanks for sharing your feedback 🙂

J

SASHA PASSAGLIA

June 19, 2020 — 10:22 am

Hi Jamie! What struck me the most about your post was your note-taking actually! It instantly reminded me of bullet journals and I wonder, do you have one? You had mentioned that you have a MET note journal but I’m thinking more along the line of one for everyday life? I also love using colours and different elements of design when I note-take as I find it allows me to bring focus to certain words or descriptions and lets my eye flow smoothly across the page. It’s almost like art in a way – note-taking art.

As for the heart words: Ones I found that haven’t been listed were:

1. ear

2. hare

3. tar

4. rat

Jamie Ashton

June 20, 2020 — 12:27 am

I don’t actually have a bullet journal! For some reason I love mapping knowledge, but am terrible at mapping emotions and my daily life. I find I just don’t enjoy it as much, and then it fades and gets used so irregularly that it seems pointless to try. I guess 35mm photography is more my everyday life tracking. It has a much more tangible end result and memory construction pattern for me. That said, not-taking art for school work or designing infographics for clients that need information shared is a passion of mine! Strange, isn’t it?

WOW! More words! Loving this!