There were many changes in the way that books were being read and distributed in the 18th century.

Publication in the 18th c. grew very quickly. At around 1800, there were seventy to eighty novels published a yea, compared to the twenty-five published a year at around 1750. It was an increasingly competitive marketplace.

The novel became an increasingly prominent and dominant form of publication. The first English novel published was Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe in 1719. Scholar Margaret Anne Doody argues against this, and states that “the Novel as a form of literature in the West has a continuous history of about two thousand years”. Nonetheless, novels achieved prominence during the Eighteenth century.

Circulating Libraries

The circulating library greatly influenced the format, distribution, and publishing of books in the 18th century, including Pride and Prejudice.

Books were expensive in the eighteenth century. The first edition of Pride and Prejudice was priced at 18 shillings, which is the equivalent of $700 CAD today, considering the buying power of the average British worker. Thus, book collecting was restricted to only the most affluent readers. This high price was caused by inflation caused by the Napoleonic Wars. The prices of novels were four times as much as they were before the Wars.

The modern public library as we think of it today did not exist in the 18th century. Public libraries today are usually owned by a municipality, open to all residents, and non-profit organizations. Usually free, readers browse in stacks for titles. Public libraries also have very generous borrowing policies. For example, Vancouver Public Library allow readers to borrow a maximum of 50 library items at one time.

The Circulating Library, showing the variety of titles available from circulating libraries, including plays, sermons, history, romances, and novels. (image from janeaustensworld.wordpress.com)

The circulating library is very different from the public library as we understand it today. Circulating libraries were privately owned and run commercially for profit. Readers had to pay a subscription, which in Regency times, started at one Guinea annually, the equivalent of 21 shillings (or roughly the cost of one three-volume novel). Readers could pay more for the privilege to borrow more books at one time. Even at this price, the circulating library was not accessible to all as not everyone could afford the subscription fee.

Readers at circulating libraries chose their books from a catalogue, or a list of titles that the library has. Moretti argues that the use of catalogues influenced the titles of novels. He states that “libraries couldn’t waste space on a catalogue page, they didn’t want confusion between this novel and that”, and thus long, descriptive titles that were widely used in the past were phased out. “Very short titles: one, two, or three words”, usually catchy, became the norm.

Circulation libraries had an important role in shaping the way books were distributed, and even down details such as how they were named. Very importantly, they also increased the number of books readers have access to without having to purchase them.

The three-volume novel

Circulating libraries also had impact on the way works were formatted, and in particular partially responsible for the emergence and popularity of the three-volume novel.

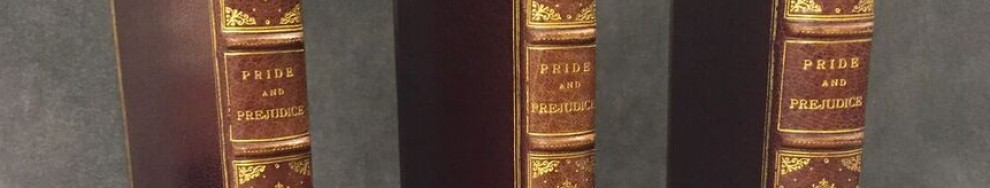

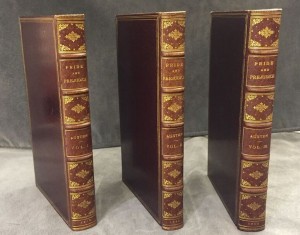

Pride and Prejudice Volumes I, II, and III. From UBC Rare Books and Special Collections

Due to the three-volume novel, circulating libraries could charge three times the amount for one work. This format influenced the writing of the works , where writers included cliffhangers in their writing at the ends of volumes to keep the reader interested in borrowing the next volume to find out what happens. Here is an example from Pride and Prejudice:

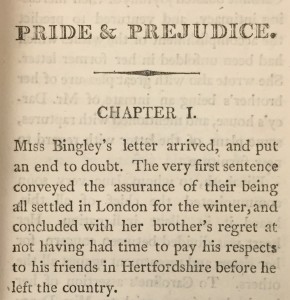

Page 1 of Pride and Prejudice Volume II.

Volume I of Pride & Prejudice ends with the Bennets (and the reader) unsure about whether Mr. Bingley, Jane Bennet’s love interest, will return to Netherfield Park. The beginning of Volume II resolves this problem.

References

- The True Story of the Novel. Margaret Anne Doody 1997

- “The Literary Marketplace” by Jan Fergus. In A Companion to Jane Austen, edited by Claudia L. Johnson, Clara Tuite. 2012.

- “Regency Circulating Libraries – Why, How and Who?” from The Regency Redingote. regencyredingote.wordpress.com. 2011.

- “Circulating Libraries” by Edward Jacobs. From The Oxford Encyclopedia of British Literature, edited by Davis Scott Kastan. 2006.

- “Glossary”. The Broadview Reader in Book History. Edited by Michelle Levy & Tom Mole. Broadview. 2015

- “Style, Inc. Reflections on Seven Thousand Titles (British Novels, 1740-1850)” by Franco Moretti. In The Broadview Reader in Book History.Edited by Michelle Levy & Tom Mole. Broadview. 2015.

- “Loan Periods, Fines, and Charges” Vancouver Public Library.