I have always had an interest in the concept behind ecotourism. The idea of fusing tourism and conservation, and producing a economically and environmentally sustainable organization seems like a long term solution to the difficulties of making reserves, particularly in a world that prioritizes economic over intrinsic value. I also have a fasination with nature, and hope to visit some of these ecotourism locations I researched one day.

My curiosity in this subject was also founded in my plans to travel and work in South Africa this summer. I’m working with an organization called “Cheetah Outreach”, which is an “education and community-based programme created to raise awareness of the plight of the cheetah and to campaign for its survival.”.

A 9 month old cub on grounds of Cheetah Outreach, where I will be working this summer!

After receiving this internship, I became increasingly interested in different ecotourism projects and their design, and then decided it would be a great topic for my paper!

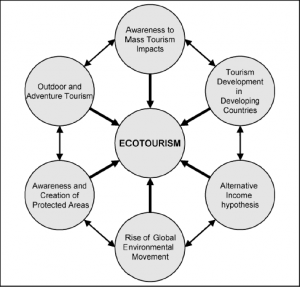

But what exactly is ecotourism?

Ecotourism, by definition of the Ecotourism Association of Australia, is….

“Ecologically sustainable tourism with a primary focus on experiencing natural areas that fosters environmental and cultural understanding, appreciation and conservation.”

What are some examples of ecotourism? My paper focuses mainly on the theory of ecotourism, but ecotourism can range from going on a tour through Kruger National Park in South Africa (pictured below) to turtle watching on the Osa Peninsula in Costa Rica.

A Giraffe crossing the road in Kruger National Park. The park offers several guided safari trips, several of which are overnight. It also acts as protected reservation for several populations of species such as lions, African buffalo, elephants, hyenas, and many more.

The rest of this site will give an overview of ecotourism, with a few examples. The different categories of history,values, regulation, economics, and biological knowledge can be browsed by simply scrolling down the page, or clicking the different tabs under the “Menu” label.