Donna Trembinski, St. Francis Xavier University

Western-style universities were founded in the Middle Ages. One doesn’t need to look very far to see evidence of this today. The pageantry of university gowns and ceremony, fraternities, common meals in refectories all stem from medieval antecedents. For the most part, such medieval-inspired nostalgia on today’s university are the generally frivolous trappings of an institution steeped in history, or, more accurately for Canada, an institution that wants to project the image it is permeated with history and custom. Not all medievalisms in university settings are so harmless, however. For instance, most universities in Canada police their own communities. They have codes of conduct that are expected to be followed and infractions of the codes are policed by internal security forces and internal justice systems. That modern universities in Canada have become essentially a law until themselves is somewhat surprising, until we remember that this too has its roots in the structure and operations of medieval universities.

The oldest university in Europe is probably at Bologna, founded in the mid-eleventh century. Soon after, other centres of higher learning were founded; Oxford and Paris by the end of the twelfth century and many others in the decades after that. Before the advent of these centres of higher learning, monasteries, cathedrals and mosques were the centres of higher learning, and indeed, medieval universities retained many of the characteristics of learning that had developed in these religious institutions. Just as institutions of higher learning grew enormously in Islamicate lands in the period from the 10th-14th c, so too did medieval universities. By 1400, there were more than 40 universities in Europe. Almost all these universities still exist in some form or another today.

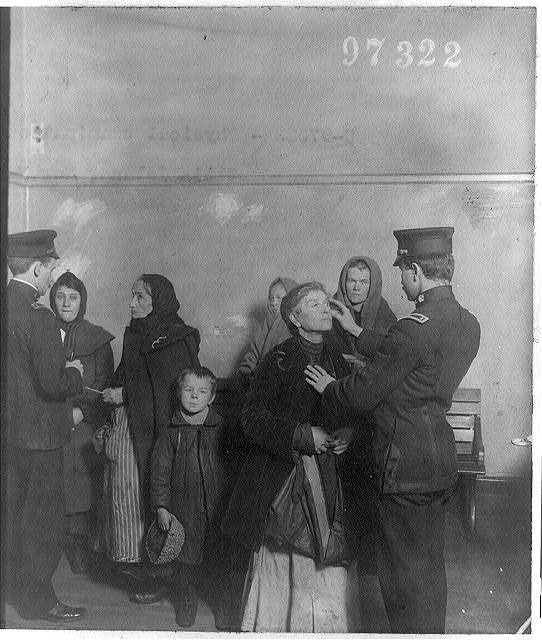

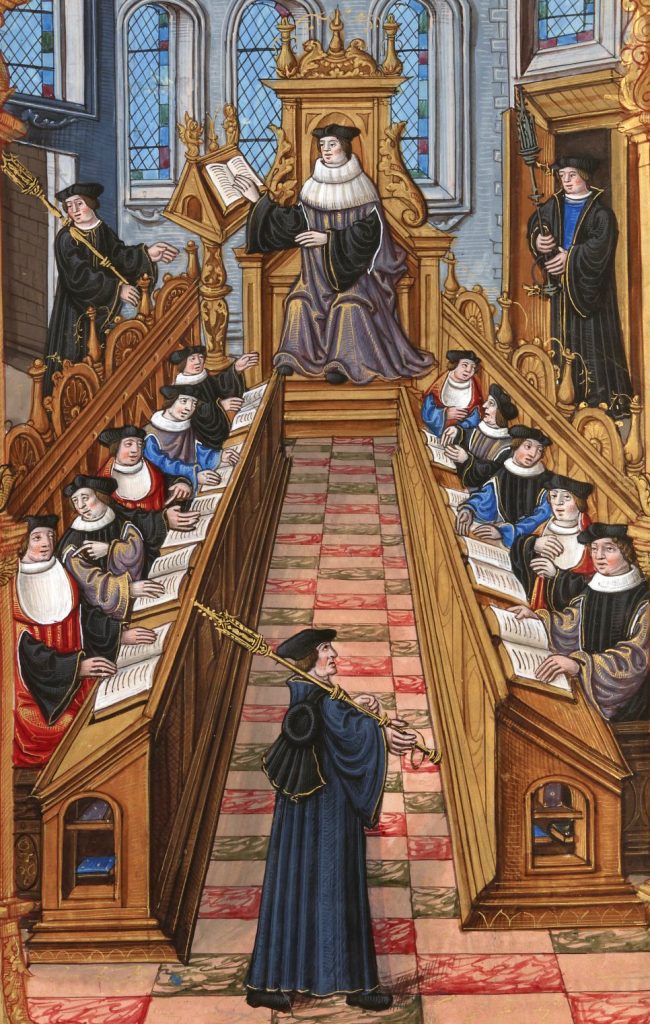

Figure 1: A sixteenth century image of masters in robes at the University of Paris

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Medievalism in modern university settings has not yet merited a great deal of attention, but evidence of the medieval origins of the institution and nostalgia for that medieval past can be found all over university campuses. The black gowns and colourful “caps” students wear for ceremonies? Those have their origins in the clerical robes most students wore in the Middle Ages (See Figure 1). Oral examinations or defenses? These too, have their origins in the disputationes of medieval universities, in which students and masters debated the important intellectual questions of the day. Fraternities and houses? Those too, are explicitly medieval. Called nationes each house had its own distinct character.

A less clear, but nonetheless apparent medieval lineage can be found for university codes of conduct and disciplinary tribunals; a university’s own “court” system tasked to mete out justice and penance when infractions occur. Students at medieval universities were clerics. This meant that they were maintained by church funds and were regarded as members of the church. As such, university students had the right to be tried in ecclesiastical courts rather than town courts when they committed crimes. Functionally this meant that many universities had their own courts with jurisdiction over students and other members of the university community.

Figure 2: A medieval illumination showing students drinking and being sick.

Source: The Times Higher Education

This became a bone of contention between university students and towns people, especially as medieval university students had a reputation for participating in the more unsavory aspects of university life, drinking, carousing, fighting. Students frequently clashed with local landlords, pub owners, merchants and town officials. But when they were called to face the penalties of their crimes, town officials had no recourse but the university courts which were more favourable and lenient to students. Punishments in these courts generally consisted of doing penance and small fines, rather than the corporeal punishment that might have been meted out in town courts. Understandably, medieval townsfolk sometimes resented the privilege students had to be tried in university courts.

Though some of the powers of university courts were stripped in the early modern and modern periods, to a large extent, universities still police themselves as they did in the Middle Ages. Most universities have codes of conduct by which students are expected to abide. These codes of conduct regulate all manner of infractions from sexual assault, to academic misconduct like plagiarism and cheating, to prohibited drug use on campus. Though many infractions regulated by student codes of conduct are criminal and, as such, governed by federal, provincial or local laws, policing, investigation, judging and sentencing still often occurs only within university processes and amongst university personnel, far removed from other legal bodies. This extensive power of protection is directly rooted in medieval models of university life and privilege and has, in some cases, at least appeared to allow universities to gloss over or ignore problematic behaviors by both professors and students.

At first glace, university code of conducts and attendant processes may not appear to be medievalism as it is generally understood, a nostalgia for a sanitized and fundamentally false version of the Middle Ages. However, modern universities have fought to retain and even enhance their rights to police their own communities, believing the institutions to be a community of their own, both a part of, but also separate from, the usually urban community in which they exist. This comes, at least in part, from a modern agreement with the quite medieval notion that members of the university community are different and so deserve special and favoured treatment. This is nostalgia, even if it has not yet been interrogated as such.