WHO WE ARE | BODY SYSTEMS

Username: student66b

Password: @Student66b

Target Audience & Vision

The end-users of this LMS course will be grade three students, and, in-part, teachers at Suzhou Singapore International School (SSIS).

This course, designed in Moodle, has dual aims. First, it will serve as a repository for sequence of learning and resources within for teachers. This will promote longer-term sustainability in terms of resource allocation in case there is ever a large turnover in the grade-level staff at the institution (of which is common in the demographic of international educators). In addition, media, near the end or start of the school year, is often erased from the school’s servers (sometimes without teacher consult) in an attempt to regain crucial and limited server space. Backing up resources within this web-based LMS will give the planning greater permanence. More importantly, the second aim for this course is to be used as a resource for students. The course is designed to support and guide instruction both inside and out of the classroom in addition to catering to differentiation of ability. Content missed within the classroom can carry on beyond its borders with the affordances that web-based instruction offers.

The pedagogical content contained within the course satisfies one of the six programmes of inquiry (PoI) of the International Baccalaureate’s (IB) Primary Years Programme (PYP) curriculum. This course will focus on the grade three inquiry into “Who we are” and its further defined scope by its central idea of “The body is made up of many systems that are connected to one another”.

Since the face-to-face (F2F) learning structure of units of inquiry (UoI) within SSIS are (mostly) six weeks long, the online planning, in terms of desired length for this course naturally unfolds. In the physical spaces of the grade three classrooms, four to five weeks is spent inquiring about five body systems, each containing its own formative feedback channel from the learning activities. This prepares children and gives them enough support in order for them to have greater success in their summative project, where they make their knowledge attained from the UoI visible. The online equivalent will be no different: Five initial topics, each representing a week of learning about a specific body system, followed by a final week involved in a summative project.

Instructors

Moderators of learning and discussion will be led by SSIS grade three educators. Their behavior will be conducted in similar fashion to the 21st century facilitation role exhibited by these teachers in their classroom – learning aims will be student-centered with a focus on social contructivism and distributed cognition. Teachers will moderate discussion only when necessary, spending the majority of their time taking the role of observers, whilst fostering and promoting rich discussions.

Since this course will be used to support in-class learning beyond the borders of the classroom, teachers can still be available for F2F discussion, if needed. However, teachers will be available within the forum spaces on Moodle, in addition to being accessible via email, the class blog and even Evernote’s asynchronous Work Chat feature which is used amongst parents, students and teachers within the grade.

Feedback from instructors will be, as Garrison & Anderson (2003) suggest, “ongoing, frequent and comprehensive”, like that in their F2F environment (in Jenkins, 2004, p.68). However, within Moodle the feedback in topics 1-5 will be purely observational so that peers can shape the way that it is constructed. Instructors will step in, for cases where feedback from peers did not happen organically; however, it will only be done in a way to promote further peer discussion. As Bates posits, “students themselves can extend their learning by participating in both self-assessment and peer-assessment, preferably with guidance and monitoring from a more knowledgeable or skilled instructor” (2014, p.3).

During week six of the course, students will be given feedback on their summative assignment from their instructors, which will relate to how the students have achieved the success criteria given to them at the beginning of module. Students will only be given a comment and not a grade, so that the feedback may be used in a formative way to drive their learning forward in their next UoI (Gibbs & Simpson, 2004).

LMS Rationale – Why Moodle?

The course was designed in Moodle as it synergizes well with our main school LMS, DragonNet, which is also designed in the medium. After trialing the course with students, reflections will be made by administration and teachers. Overall, if the feedback is mostly positive, the course, through its design in Moodle, can easily be updated into DragonNet through Moodle’s backup, export and import features. This will synergize workflow for both teacher and student alike in terms of resources needed to negotiate and engage in learning.

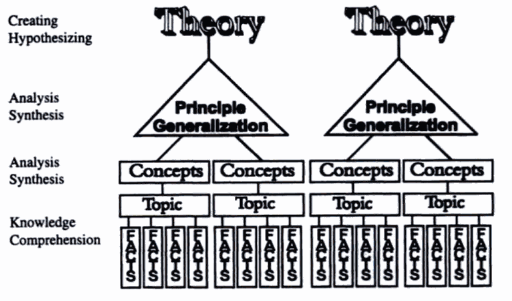

Secondly, Moodle allows for the inquiry to be broken up into manageable chunks of learning through topics. As Conrad elucidates, successful instructional design of an LMS emphasizes the main points and tasks, illustrates the connection between topics and progresses along in logical order, done at a reasonable pace (2000, p.113). Breaking concepts down further into topics also aligns well with the concept-based learning approach to the PoI at SSIS. Lynn Erickson’s Structure of Knowledge image below (see Figure 1.1) best illustrates how the concepts of form, function and connection (i.e. the conceptual undertandings/goals of this UoI/course) can be further broken down into topics in order for them to be easily understood. Moodle lends itself nicely to Erickson’s work and ultimately PYP pedagogy because facts can be contained within the topics of the LMS. Conceptual understandings can be linked to the goals of the course, which are ultimately linked back to the principle generalization (i.e. central idea) and theory (i.e. knowledge of “Who we are”).

Figure 1.1: Erickson’s Structure of Knowledge (2002)

Figure 1.1: Erickson’s Structure of Knowledge (2002)

Third, Moodle has plenty of cues and learning tools that help orient and engage the learner. As Fleming (1988) suggests, successful design in web-based learning involves the evaluation of tools and their benefit to learning (in Conrad, 2000). Moodle’s tools that will add value to this course include a glossary of terms, search features, and choice in media content that can be updated. Furthermore, the forums within Moodle allow for asynchronous online discourse to take place. Benefits of discourse promoted within these forums can be linked to theories of distributed cognition, social contructivism and formative assessment. Distributed cognition theory posits that learning happens in conjunction with others with the support of cultural tools and implements (Hollan, Hutchins, & Kirch, 2000). Meanwhile, Vygotsky’s social constructivism maintains that learning happens based on connections to prior knowledge in socially constructed environments (Driver, Asoko, Leach, Mortimer & Scott, 1994). Not only are the forums a tool for learning to be constructed and consolidated in a social construct, they can also be a mechanism for students to receive feedback within a safe environment (Jenkins, 2004). This formative feedback, according to Gagne (1997), helps connect prior knowledge with the new material, gives children a focus, encourages active engagement, helps children monitor their progress towards mastery and offers plenty of opportunity to apply their new knowledge and consolidate it in authentic activities (in Gibbs & Simpson, 2004, p.11-12). Put more succinctly by Chickering & Gamson (1987), “Knowing what you know and don’t know focuses learning” (in Gibbs & Simpson, 2004).

Lastly, Moodle affords the users an online, social contructivist space conducive to collaboration. This helps “promote peer support, the creation of authentic and applied tasks, and an environment for reflection” (Jenkins, 2004, p. 74).

Accessibility

Moodle does have some limitations, in terms of accessibility in China, meaning that the Great Firewall (GFW) has flagged some scripts within the site in order for it to be quickly accessed. Luckily for SSIS stakeholders, its board of directors has recently approved several internet lines direct from Hong Kong that allow access to learning sites, like Moodle, without censorship. Thus, no virtual private network (VPN) is required to access the site anymore; users just need to be cognizant to switch the Wi-Fi to that of the Hong Kong direct line. This has been very successful since the start of this year, with only minor glitches that have resulted in very little loss of access to learning. This being said, government policy changes do happen very rapidly in China – having approval to use overseas internet today, does not mean that it will be the same tomorrow.

Security

For better or worse, SSIS is a not-for-profit private institution. It aims to provide an excellent and rigorous education to children of expatriate families and is authorized by major international institutions, not limited to the IB. With this in mind, it does have the advantage in increased flexibility and reduced timelines in its policies pertaining implementing new educational technologies. This also applies to governance of major decisions that surround the safety of children. For example, when applying to SSIS, parents must sign a disclaimer that any material used for learning, including student photos and videos, may be used for promoting the school. This does not exclude social media channels such as Twitter, WeChat, Facebook and Instagram. However, the school is very cognizant of the protection of minors and teachers must abide by policies that include using first name only (pseudonyms preferred) and to try to limit facial exposure as much as possible.

How does this tie in with Moodle? Media content of minors, including photos and video may possibly be stored within Moodle and its courses. If the Pentagon or major governmental agencies can be hacked, who’s to say that Moodle couldn’t either? Regardless of where content is stored and legalities with ownership of content, digital content, whether stored locally or on the cloud is breachable. It’s a 21st century risk we take and must be advertent to. Open-sourced software is a calculated risk; it has its power in numbers of contributors out there – meaning that common interest usually prevails. Also, because of Moodle’s GNU public licensure, it promotes transparency in its practices so they can be explicitly and universally understood by all.

Moodle’s acceptance by the board of governors and administration has already sought approval and has been in use for years at SSIS. As mentioned previously, DragonNet, SSIS’ intranet for resources, bookings and LMS for some high school courses, is all done in Moodle. Therefore, the “red tape” in implementation is minimal since boxes have already been ticked and there is no additional financial cost towards using the medium due to its free use.

Corporate Influence

When introducing any new program into a learning institution involving minors, teachers and administration should be cognizant of the corporate influence and branding that children will be subjected to. Learning institutions must ask themselves how right is it for schools to brand themselves as “X Corporation” schools, particularly when aligning themselves with educational technologies. Of particular importance, is whether or not the company promotes a positive image towards humanity. A foreign company choosing to assemble in products in nations where it can pollute more and pay and treat workers less than in the nation of its origins, should signal a few warnings. If children do not have a voice or rights to vote as political citizens within their own nations, then does that also include stripping them of their right to vote as commercial citizens (Banet-Weiser, 2007)? Open sourced software programs, like Moodle, promote good messages to minors – collaboration, sharing, transparency and giving.

References

Banet-Weiser, S. (2007). Kids rule!: Nickelodeon and consumer citizenship. Duke University Press.

Bates. T. (2014). Appendix 8. Assessment of Learning. Teaching in a Digital Age. (online book)

Conrad, K. (2000). Instructional Design for Web-Based Training. Chapter 5: Defining Learning Paths (pp. 111-136).

Driver, R., Asoko, H., Leach, J., Scott, P., & Mortimer, E. (1994). Constructing scientific knowledge in the classroom. Educational researcher, 23(7), 5-12.

Erickson, H. L. (2002). Concept-based curriculum and instruction: Teaching beyond the facts. Corwin Press.

Gibbs, G., & Simpson, C. (2005). Conditions under which assessment supports students’ learning. Learning and Teaching in Higher Education, 1(1), 3-31.

Hollan, J., Hutchins, E., & Kirsh, D. (2000). Distributed cognition: toward a new foundation for human-computer interaction research. ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction (TOCHI), 7(2), 174-196.

Jenkins, M. (2004). Unfulfilled promise: Formative assessment using computer-aided assessment. Learning and Teaching in Higher Education, i, 67-80.

Lee W., Owens D. (2004). Multimedia-Based Instructional Design. Chapter 23: Developing Computer-Based Learning Environments. p. 181-189.