Two years ago, I took a family trip back to China. The purpose of the trip was to reconnect with relatives, but for my dad, his most pressing goal was to find the cheapest, biggest, most up-to-date drone that he could get his hands on.

Drones are currently the hottest product within the tech industry and are a must-have cool kid toy for any serious tech head, aspiring videographer, or amateur surveillance professional (home security can be a serious matter). Apart from their obvious recreational uses, drones are being steadily implemented into various industries to help in ways that have surpassed many expectations. From its roles in Amazon’s Prime Air delivery, to Dubai’s drone taxi service, and even to their data-collection role for American insurance companies during the recent hurricane devastations in Texas and Florida, drones have become a hot commodity.

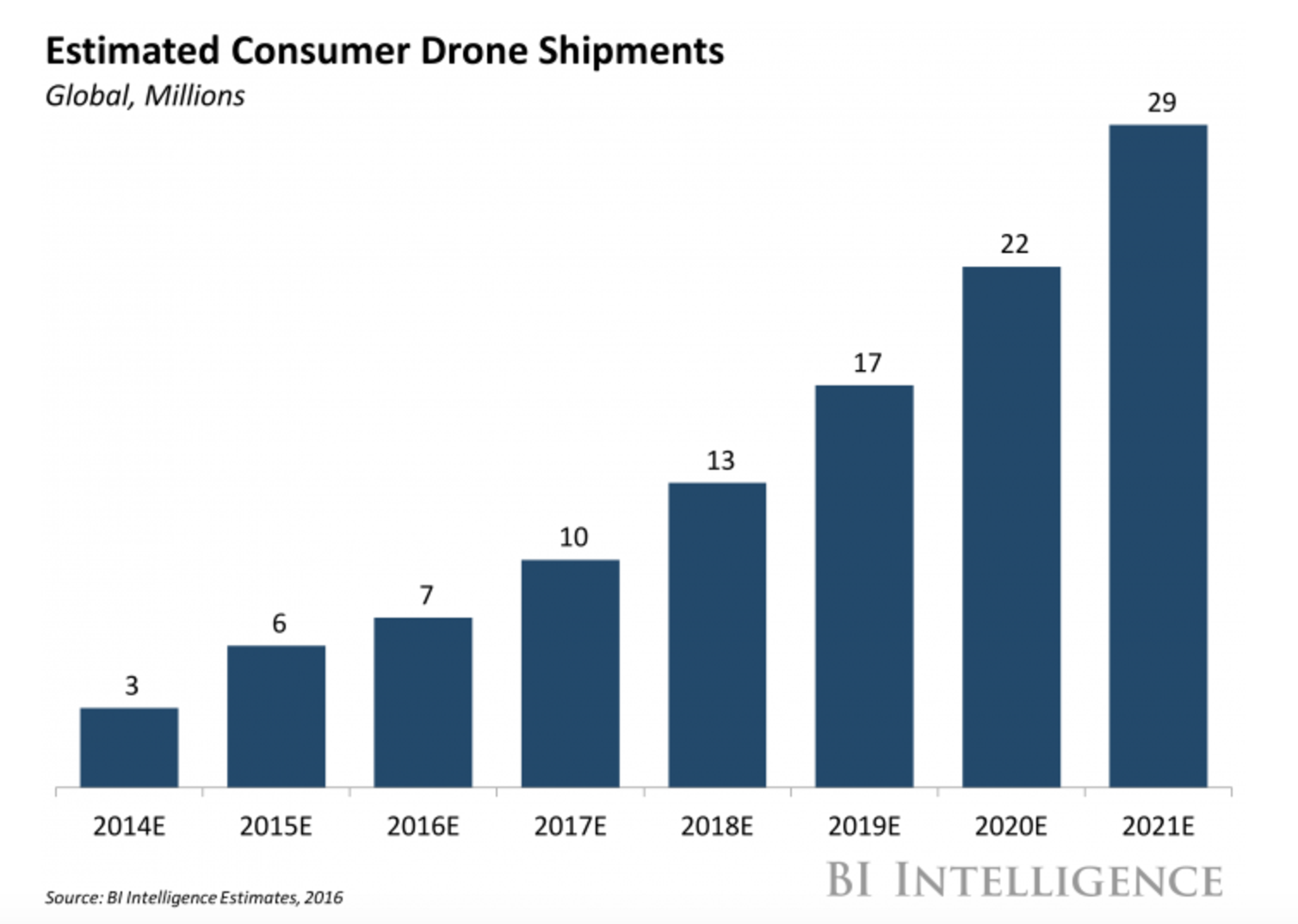

The reason behind the drone’s exponential success can be attributed to the product’s versatility that crosses over multiple sectors of use that has the potential to revolutionize entire industries. In response to the overwhelming demand, the industry has boomed within the last couple years, with 2.4 million personal drones being sold last year in the U.S. alone – double what was sold the year prior.

While many may look upon the industry’s booming growth in awe, I view the numbers with alarm, because, with innovations like drones comes a lack of boundaries, and from there, major safety and privacy concerns that require the right form of regulation. Our current global regulatory controls are just not able to keep up with the rapidly changing unmanned-aircraft technology.

With new product upgrades coming in every few days, regulators are just unable to guard against major concerns and threats that drones pose, including airspace threats, privacy invasion, corporate espionage, and civilian accidents. Therefore, I find it completely necessary for governmental bodies to implement and enforce regulatory laws for the use of drones.

I believe that all consumer drones should be prohibited to fly below 400 feet over any permissible public or private property and that any drone-user wishing to fly higher must register a license with their municipality. Furthermore, any offenders should be fined as a warning to others. While these restrictions might seem overly rigorous, I believe it to be necessary for the time being so as to allow time for regulators, officials and industry leaders to develop a global operating standard for unmanned flying vehicles.

While the limitless possibilities for drone usage is an exciting prospect, they can only be used to their full potential with the right controls in place. So, until governments are able to pass these regulatory laws, I can only say, “Heads up”!

Word Count: 448