To conceal or to reveal is the question.

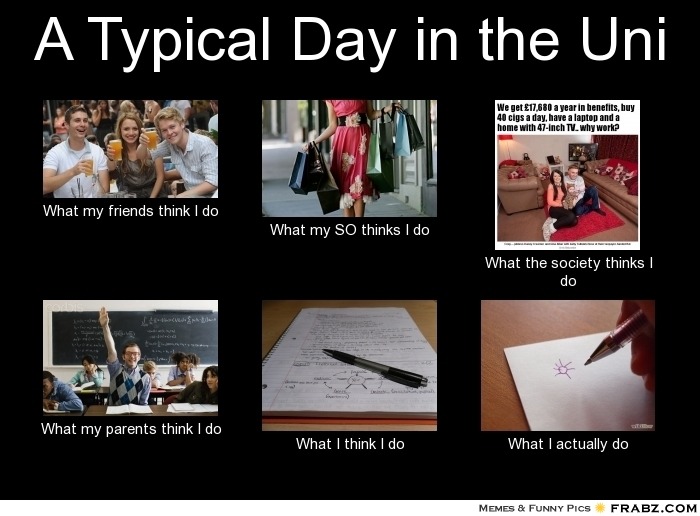

When you’re sitting down at the Thanksgiving dinner table and your ol’ Uncle Dave asks you “How is university going?”, you might want to say that your courses are very interesting, that you’re enjoying your professors, that you’re studying hard and that you’re doing well. But how true is this really?

Did you happen to mention the fraternity party you went to last Friday night? Or the nights you procrastinated until 12:00am and stayed up until 4:00am, convincing yourself you were being productive? Or how about the time you barely passed that midterm that you started studying for the night before? Did you mention how you’re secretly dying on the inside just trying to survive this crazy thing we call university; by balancing all of your classes, your millions of readings, your social life, getting a workout in here and there, trying not to check your bank balance as much as possible, attempting to get a good 8 hours of sleep but in reality only getting 4 or 5, remembering to eat 3 meals a day, being a part of 1, 2 or 3 clubs, councils, sports teams all the while keeping a happy face plastered on when you get asked the dreaded: “How is university going?”

We have all been there.

This idea to conceal or to reveal comes up in our day-to-day lives, whether consciously or subconsciously, each and every one of us is guilty of concealing certain things in our lives while revealing others. What we reveal to others varies by who we are interacting with; our teachers, our professors, our parents, our friends, our co-workers, our classmates, people of the opposite sex, employers, etc. We generally have the tendency to want to reveal things about ourselves and paint ourselves in a rather positive light such as what we reveal on social media, what exam marks we choose to or to not reveal or what we choose to reveal about ourselves during ice breaker activities. Sometimes, however, we choose to place ourselves in a negative light such as when we tell our friends of how little studying we have done, how little sleep we have gotten or of how much of a clutz we are.

This idea of concealing and revealing also applies to our memory, of what memories we choose to reveal to the public and of what kinds of memories we choose to conceal and to keep to ourselves. Marita Sturken, a communications scholarly writer, writes in her book: “Tangled Memories: The Vietnam War, the AIDS Epidemic, and the Politics of Remembering” about cultural memory and how cultures have the tendency to forget certain parts of the past by using a form of forgetting that is both “highly organized and strategic” (Sturken, Tangled Memories 7). As Dr. Luger mentioned in our ASTU class, Canada, as a nation has done its best to conceal the Japanese Internment from our cultural memory in an attempt to strategically forget the suffering, trauma, and torture that we caused over 20,000 Japanese people from 1941 through to 1949. Our country is not proud of these actions and of this xenophobia that the Canadian government and its citizens felt during this time period. As a result, we all choose not to reveal this part of our history but to conceal it as much as possible.

According to Sturken, cultural memory is produced through representation-in contemporary culture, often through photographic images, cinema, and television” (Sturken, Tangled Memories 8). She then questions the idea of whether or not it matters if we remember “correctly” and how accurate one’s personal memory or cultural memory really is. Yes, cultural memory is produced in various forms such as in film, television and photographs and from all sorts of different perspectives-but what are these various sources choosing to conceal or choosing to reveal?

How many times do we really reveal the full story?

… If the full story is rarely revealed, how are we supposed to remember the past accurately and truthfully?

…Does this mean that we always have an inaccurate memory of the past?

Recent Comments