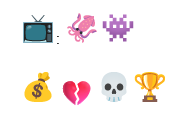

Despite the simplicity of emojis, the task of using these images to represent long form media (i.e. a TV show) proved to be quite challenging. While I could use emojis to capture key ideas like money, betrayal, death, and competition, expressing its deeper themes such as inequality, morality, and survival proved more difficult. This highlighted the strengths and limitations of emojis as a semiotic tool: they’re highly accessible and immediate but often struggle to convey abstract or nuanced concepts (which makes sense given their pictograph form).

What stood out to me is how emojis function as a hybrid between traditional text and visual representation. For instance, they are often arranged in a left-to-right sequence, encouraging a linear reading path similar to text. At the same time, they possess the flexibility of images, allowing readers to interpret or reorder symbols in different ways depending on their perspective. While I arranged the emojis in a particular order to suggest the plot of the story, others could approach them from different angles, focusing on specific elements or rearranging the sequence, and still extract meaning. This hybrid nature reflects Kress’ (2005) discussion of how reading and writing practices are changing in the digital age. In traditional text, authors hold significant control over meaning, as readers rely on the sequential order to uncover ideas. By contrast, visual modes like images give viewers the freedom to interpret spatially. Emojis combine both dynamics: they invite linear reading while also allowing for nonlinear, reader-driven interpretation (Kress, 2005, p. 13). As said by Kress (2005):

“Where with traditional pages, in the former semiotic landscape, it was the power of the author that ruled, here, it is the interest of the reader, derived from the contingencies and needs of their life-worlds.” (p. 18)

This shift from author-driven to reader-driven meaning-making also reflects broader social changes. Kress observes that digital communication gives readers greater agency to navigate and interpret multimodal texts according to their own contexts and needs. Parallels can also be made to Bolter’s (2001) assertion that this development (i.e. the growing primacy of the visual) is leading to “a readjustment of the ratio between text and image in the various forms of print (books, magazines, newspapers, billboards), and the refashioning of prose itself in an attempt both to rival and to incorporate the visual image.” Accordingly, emojis exemplify this trend, blending the structure of text with the openness of visuals to create a flexible form of communication (albeit with the aforementioned limitations).

References

Chapter 4. Bolter, J. D. (2001). Writing space: Computers, hypertext, and the remediation of print (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Kress, G. (2005), Gains and losses: New forms of texts, knowledge, and learning. Computers and Composition, 2(1), 5-22.