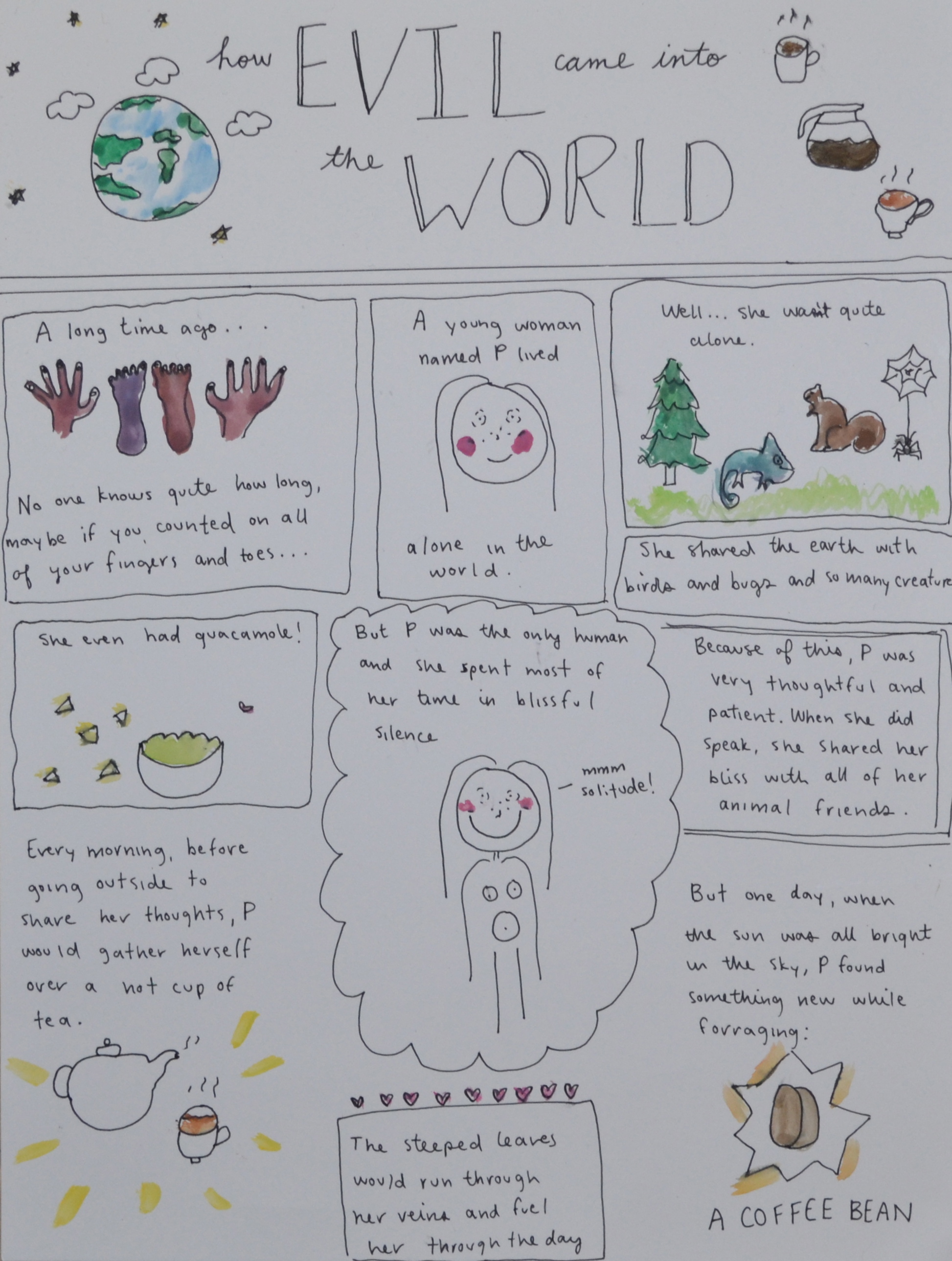

Question 3: Words. Chamberlin talks a lot about language, in particular the strangeness and wonder of how language works. Stories, he says, “bring us close to the world we live in by taking us into the world of words” (italics mine, 1). He describes learning to read and write as learning “to be comfortable with a cat that is both there and not there” (132). Based on Chamberlin’s understanding of how riddles and charms work, explain this “world of words.” Reflect on why “words make us feel closer to the world we live in” (1).

For the past two years, I have been the proud best friend of my roommate’s cat, Sprite. Sprite, my roommate and I’s house was recently torn down, so we were forced to part ways, but up until this, our cohabitation involved a lot of this:

sprite

Sprite is a strange cat in that she is a purebred Ragdoll. She has been (in)bred to be docile and passive, and is thus even more floppy and sleepy than your average cat. I understand that this is not exactly what Chamberlin was speaking about when referencing the cat that is both there and not there (in Sprite’s case, not there meaning asleep 20 hours of the day), or herding cats (my kind of cat-central-metaphors kind of guy); but it did get me thinking about the elusivity of something we hold so closely as part of our self-actualization: language.

I ended up at a previous student’s blog for a previous semester of this course, who explained that the cat as both there and not there is a reference to a thought experiment conducted by Erwin Schrödinger that explored imagination and reality as the ultimate paradox. Kk, sorry Erwin, philosophy is not really my jam, but this notion of reality and imagination as not so much polar, but symbiotic makes (a little more) sense with regard to Chamberlin’s “world of words”.

In describing the relationship between imagination and reality as symbiotic, I do not wish to confuse Erika’s discussion of the symbiotic relationship between story and literature–though the two pairings do seem to go hand in hand. Words and language are much like my pal Spritey because as much as the speaker/writer is in control of them–feels as though they own and raise them intentionally–they are also 1) not something entirely created by the speaker, their own entity that came from past relations/history/beings 2) available to others (readers, listeners and other speakers) to be interpreted and used. The connotations of language are aloof to the speaker: as Erika notes, the control and power is messily and foggily exchanged between writer and reader, speaker and listener. While storytelling allows for more context, energy and emphasis to be added that can influence the listener, the speaker is still very much in a vulnerable state in presenting their reality through words: does the reality need to be confirmed by listeners in order for it to be actualized. Through how many variations of hearing can a story go for power to come from shared belief?

In the context of discussion around colonization, forgetting and unlearning, power seems to be a separate factor: something that is not entirely born from shared stories and belief, but something that pre-exists due to histories of violence and misunderstanding (I fear that misunderstanding is too gentle a term, but alas I am limited in the world of words). When histories are intentionally forgotten on an institutional (and thus, national) level, not only do the connotations and meanings of words veer strongly out of the favour of certain (read First Nations) groups, but ways of using words to exhibit knowledge, belief and consequent reality are challenged and ignored.

Macneil’s discussion of orality was a much needed read, because I have been exceedingly frustrated by this binary of “literacy”–and the horrors of “illiterate” groups–“illiterate” women around the globe. Last summer I did an internship at a library in Busolwe, Uganda. I was doing impact assessment on this language decolonization program for elementary schools. ~~I have, to the point of nausea, one million things to say about the fact that I was even working abroad, especially in what would be considered a “development” situation, so hit me up if you ever want to chat over a beer, because I can’t type it all out on this bad boy.~~ The thing about Uganda is that it is seen as one of the *best* countries in East Africa if we’re talking about stability and the UN Millennium Development Goals; on that note, the thing about Uganda is that elementary school is taught in home vernacular until grade three, before a straight up switch where everything goes to English. whaaat. Because of this (again, I need a beer), there is a tonne of internalized inferiority, a huge drop in grades and “literacy”/the learning curve and a very estranged relationship to language. What I noticed especially was that, because English was this language specific to (Westernized, high emphasis on science, math etc.) school and studying, students used the language very clinically–self expression, story telling and poetry were kind of out of the picture when speaking English. But at the same time, students are punished when speaking their family dialects, so that is kind of limited too–or there is a certain amount of shame associated with it. For so many people, language (speaking and writing) is a primary medium for self-expression. Self-expression is a confirmation of self: a cumulation of experiences that confirms one’s existence, reality and validity. To force Eurocentric ideals, and colonial languages is to challenge the realities of groups, histories and individuals. THIS IS IN NO WAY MEANT TO BE ME TELLING THE STORY OF THE “DISEMPOWERMENT” OF THE PEOPLE IN BUSOLWE. I feel vulnerable in my own words here, because I hope in no way to be taking some kind of anthropological, “look what we’ve done”, labelling of the “victims” of colonialism. This is just one slice, one story/perspective to illustrate a point of the power of words and language and how tied to history “legitimate” ways of knowing can be.

Continuing with this, the documentary Schooling the World: The Last White Man’s Burden calls bullshit on the current trend in international “development” toward building schools to tackle illiteracy. The main point is that for some reason, the building of Western-style schools doesn’t seem as inherently racist or ignorant as, say, Christian religious missions, due to this assumption that education and literacy is “higher” in the hierarchy of needs and thus universal. But the reality is that going into situations to eradicate “illiteracy” is to claim a terra nullius on the knowledge and histories of the families and groups being approached. The film notes that inferiority is internalized in a twofold manner: children are taught that they are essentially being saved from the ignorance and poverty of their families through these new, Western schools (presumably being “built” by white voluntourists) and elders are being told that they have nothing valuable to teach to the young people in their communities. Additionally, when the kids taught in these Westernized elementary schools don’t succeed at becoming doctors, they don’t have the knowledge of their families/communities, and aren’t really useful at, for example, subsistence farming. It is kind of like a displacement of knowledge that can lead to literal displacement of people.

These examples of current-day colonization exhibit the delicate relationship between language and reality. While there is the micro relationship between how words articulate imagination, thus creating this quasi-reality is present, on a macro level, how we determine what types and uses of language are valuable and legitimate feeds into create and denying entire histories and bodies of knowledge. This is where unlearning, though SO difficult, is valuable. Through my schooling, I’ve always been taught to “think critically”, question whatever one is being told. But the problem with this is that critical thinking mostly materializes in the form of imposing one’s subjectivity and reality onto a story/argument/artwork. Unlearning as a method of critical thought more requires criticizing one’s subjective reality to better understand all of the assumptions that are made when listening. What we hear and what we don’t hear, and why. What we choose to make real, and what we see as mere detailing.

I’m trying to think of a way to bring this back to my cat. How do you deal with the pukey hairballs of your lil fuzzy words?

love,

Jocie

Works Cited

Dada, Zara. “Imagination v. Reality, The Ultimate Paradox?” UBC Blogs. 01/17/14. Web.

Black, Carol. “Schooling the World: The White Man’s Last Burden.” A Thousand Rivers. 2010.

Chamberlin, Edward. If This is Your Land, Where are Your Stories? Finding Common Ground. Toronto: AA. Knopf. 2003. Print.

Courtney MacNeil, “Orality.” The Chicago School of Media Theory. Uchicagoedublogs. 2007. Web. 24 May 2015.