Mosquito Habitat Study at Squamish region of Howe Sound

The maps are at the bottom of the page…

Abstract

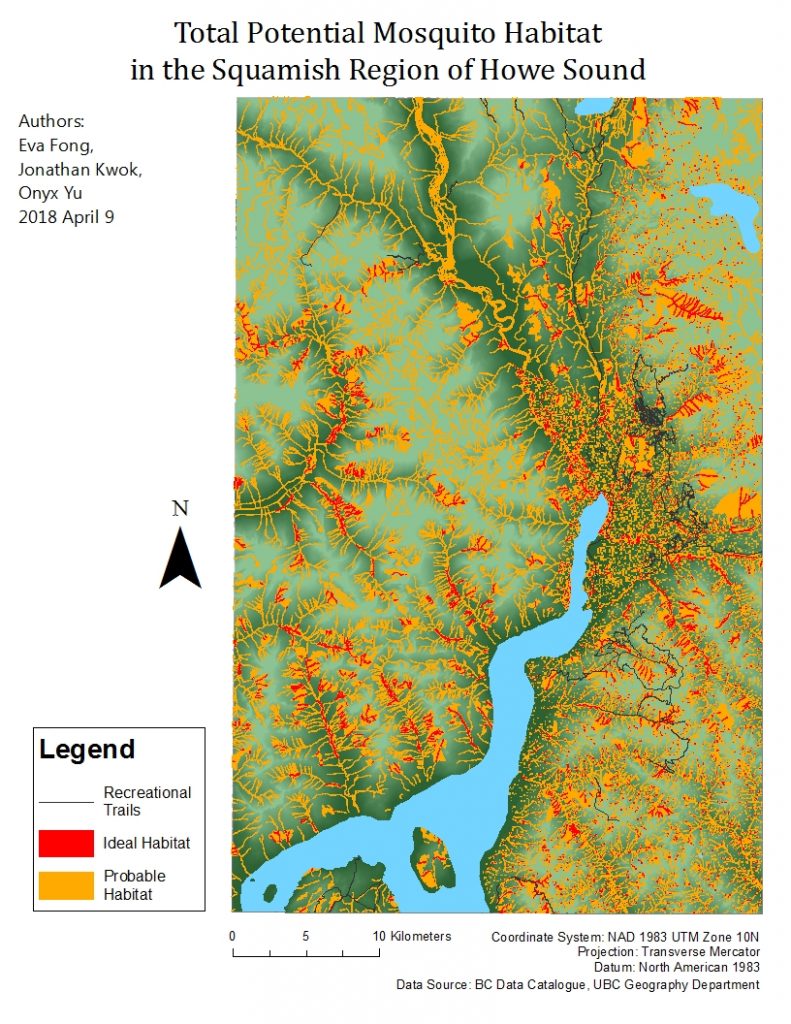

Mosquitoes are also a common insect encountered during outdoor activities in the lower mainland and Howe Sound and thus can be a nuisance to some people. Mosquitoes are well studied in other parts of the world such as tropical and subtropical regions. Using that information of prefered and potential habitat sources, a map of the Fraser Valley and Howe Sound is created to suggest potential habitat sources for mosquitoes based on moisture availability. We have also included layers like old growth forests in the region to simulate mosquito habitats besides relying solely on moisture levels. Data on the region was collected from the British Columbia Data Catalogue as well as the UBC Geography’s hard drive server. Mosquitoes prefer warm environments therefore it is assumed that this map would predict source habitats during the warmest quarter of the year. Since this was solely based on moisture levels and prefered habitat quality, it would be suggested for the next study to include other factors such as temperature, wind variance, urban and predatory interactions.

Introduction

For many who enjoy the outdoors, they don’t mind the conditions nature has to offer. Most can agree that the amount of pests can create a tipping point towards long lasting memories, or utter bitterness. In British Columbia alone, there are a total of 5 genus and 41 different species of Mosquitoes (Culicidae sp.). These aerial insects are an inevitable encounter in Vancouver’s mountains especially since our outdoor activities are located in a temperate rainforest, a moist and warm environment which is perfect for mosquitoes. Mosquitoes are also unavoidable as they are found in abundance across the globe especially in the summer in the Metro Vancouver region since the temperature is warmer. Outdoor activities are quite popular for tourists and locals in the Fraser Valley and Howe Sound regions in the summer which increases the potential for human and mosquito interaction. The goal is to map out potential mosquito habitats based on preferred abiotic conditions and breeding locations, e.g locations with sources of moisture, poor soil drainage, and old growth forests. The map will identify mosquito hotspots and will help outdoor enthusiasts predict the intensity of mosquito frequency during their activities.

Methods

Aquire

The data on local trails, old growth forest habitat, streams, and water boundaries was acquired from the British Columbia Data Catalogue. The data on park and recreation areas, topographic boundaries, and larger water bodies such as major rivers were retrieved from the data library from UBC Geography’s hard drive server. The raster data on soil drainage was also retrieved on the hard drive server.

Parse Filter

The Geospatial contained information throughout the BC province and the entirety of Canada . All Data were clipped to show just the fraser valley area to reduce background loading on ArcMaps. Elevation layer was added as a raster and converted to polygon and was used for clipping all the other files to reduce the are to the Squamish Valley and Howe Sound area (See table 1). The soil drainage data included only specific attributes such as very poor, poor, and imperfect soil drainage to complement mosquito habitats since they prefer moist and damp areas. Attributes with well or high levels of soil drainage were not selected. The soil layer was then clipped to the relevant local area.

Mine

Streams and other freshwater bodies, and known mosquito land habitats were buffered to visualise the potential total area mosquitos could travel from their source habitat. Old Growth forest are a known refuge for mosquitoes therefore old growth forest polygons were also buffered. The soil drainage raster data contained values of soil drainage levels. Very poor, poor, and imperfect drainage attributes were selected and exported as a polygon layer, which was buffered. All buffers were 50m from the edge. All files were clipped to the resulting polygon elevation layer.

Represent

The layers were projected as NAD 1983 UTM 10 since the scale of our map fit within one UTM category and it is a large scale. The color of the buffers were chosen to blend in the geography layers and the stream and water bodies without disrupting the color integrity. Colours were distinct enough to show a difference in layers and representation without disrupting the viewer’s understanding of the map.

Results

Our project is to determine a hospitable source area in which mosquitoes can be found particularly in the Squamish Valley and the Howe Sound area. We chose this area in particular as we are quite fond of hiking in the Squamish Valley and Howe Sound trails. Mosquitoes however remain as an unavoidable part of nature and often are a nuisance to most people trying to enjoy the great outdoors the Pacific Northwest has to offer, particularly during the optimal seasonal window in the summer. We decided to focus on mosquitoes for our area of study because we wanted to know which potential hiking or recreational areas might have a high prevalence of mosquitoes, making it possibly easier to avoid hiking trails or areas with a higher chance of encountering mosquitoes. Although it was difficult to find exact data on mosquito spawn locations or hotspots, we created a potential “ideal habitat” for mosquitoes by considering factors such as moisture, bodies of freshwater, old growth forest areas, potential and terrestrial habitats. We joined the layers together in order to make the “ideal habitats” and buffered water boundaries and old growth forests by 50 metres.

Summer is considered the best season to thrive in for mosquitoes in British Columbia (Belton, 1983) due to the warmest temperatures being recorded in the summer and also having a healthy amount of leaf litter in old growth forests contribute to a mosquito’s optimal habitat (Johnston et al. 2011). British Columbia is also one of the wetter provinces in Canada, receiving higher levels of rainfall and also having a higher amount of moisture in the environment allowing mosquitoes to thrive since they prefer wet conditions (Belton, 1983). Mosquitoes are also prevalent in areas where drainage is often poor, like marshes or flooded rivers, since still water is favoured by mosquitoes to have their larvae as mentioned by Mangudo et al. (2018). Areas with poor drainage often lead to increased moisture levels in environments or at least bodies of water which provide potential habitats and spawning areas for mosquitoes (Dida et al. 2018). Dida et al. (2018) mentioned that all potential mosquito breeding habitats were within 50m from a water source. We used 50m as a value for our buffers to determine the extent of the breeding habitats from our streams, rivers, and lakes. It is also described by Mangudo et al. (2018) that mosquito larvae can also be found in other dead-water areas such as tree holes from decomposing logs or still-standing dead trees. Since old growth forest contain a diverse range of tree age and species, old growth forest has been buffered as well (Johnston et al. 2011). Since mosquitoes can travel well beyond their source habitats, the buffer serves as quantifiable data of guaranteed likelihood of encountering one during the seasonal window. Outside the buffer, the likelihood of mosquito would decrease but it is still possible of encountering one due to other transportation factors such as wind (Hunt et al. 2017). However it is possible to still encounter mosquitoes beyond the buffer zone maybe due to factors such as decreased winds levels and increased temperature and moisture levels. Thus from the data we collected, we formulated it into probable habitats, so habitats that might be possible for mosquitoes to thrive, and ideal, which is the perfect habitat for a mosquito to thrive in within the Squamish Valley and Howe Sound regional area.

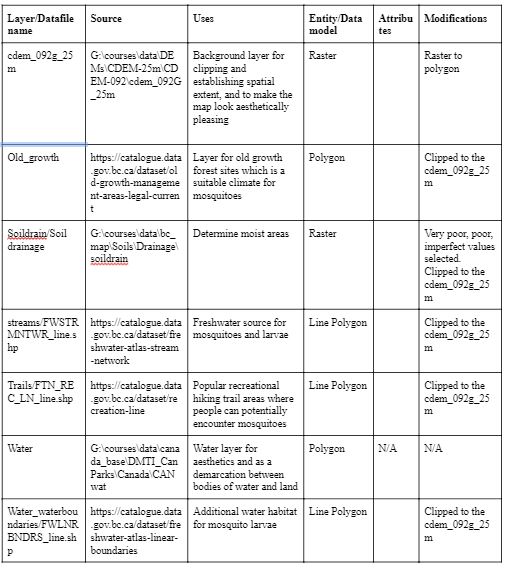

In order to achieve our results we first had to factor in various habitats mosquitoes would find suitable to inhabit or have their larvae as mentioned. Firstly, we found various bodies of freshwater sources throughout the Squamish Valley region. We used streams and lakes in the area since those are freshwater sources unlike the Howe Sound which is salt water. After applying our freshwater layers, we buffered freshwater boundaries and the streams layers by 50 metres, since Dida et al. (2018) mentioned that all potential mosquito breeding habitats were within 50m from a water source. The results we achieved for the water buffer was 77218783.823416 m² for the water boundaries buffer and 414129769.341356 m² for the streams buffer. Finally the aquatic union, the water boundaries and streams buffer combined, was calculated at 460896335.705636 m². Thus we discovered there was quite a copious amount of potential freshwater habitats for mosquitoes to inhabit but we did not account for other factors yet. The final result can be seen in Figure 1.1 (Appendices) and shows a map of the Squamish Valley region’s hiking trails with the 50m buffer for freshwater sources.

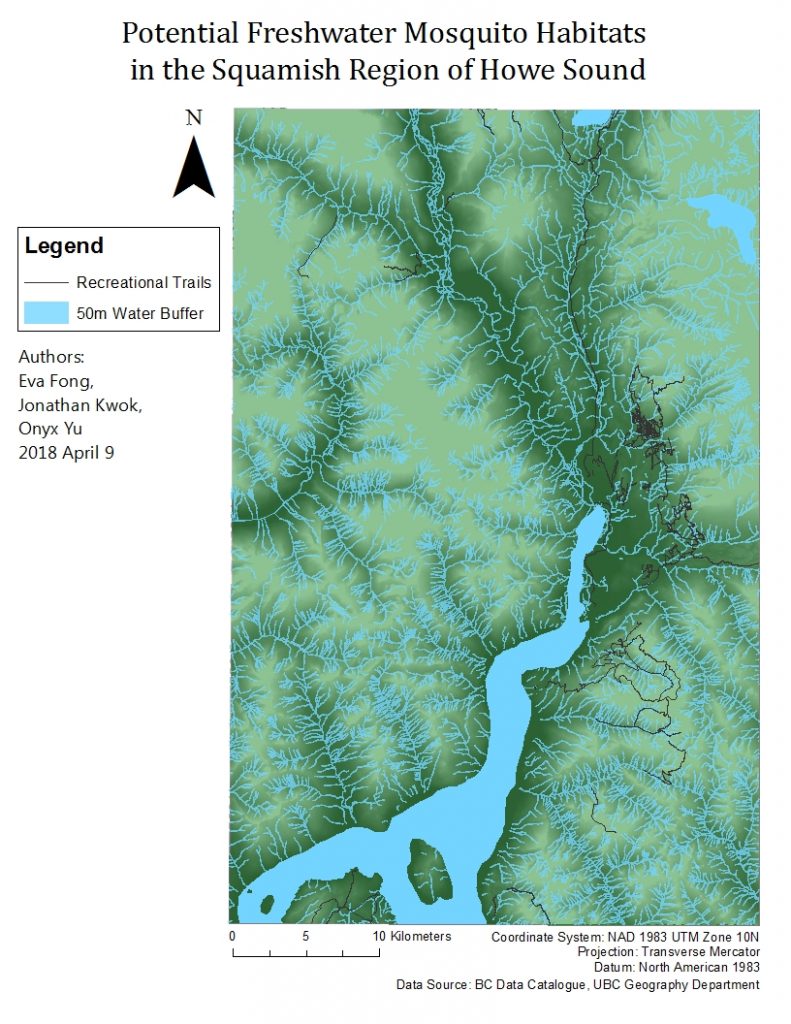

The next layer that we included which coincides with water was drainage. Mosquitoes larvae and mosquitoes are more commonly found in areas with poor drainage and also lower elevations or lack of slope, which leads to poor drainage. Poor drainage areas flood more easily than areas with better drainage leading to a higher chance of having stagnant water which is ideal for mosquitoes (Ngugi et al. 2017). In the Squamish Valley region, it is noted that low elevation areas were more prone to having poor drainage, particularly areas that were closer to the Howe Sound as shown in Figure 1.2. The total area calculated that has what Data BC (where we found our data) considers to be poor or imperfect (below average) drainage is 133702236.319973 m². Another terrestrial factor we took into account is the Old Growth Forest Area layer. Mosquitoes prefer to live in areas with lots of trees as trees provide leaf litter that make their habitat more suitable, but trees can provide mosquitoes with shelter from certain predators or weather conditions (Johnston et al. 2011). Tree holes, decomposing logs, or dead trees, are inhabited by mosquitoes as well as areas where you can find their larvae (Mangudo et al. 2018). We found data for old growth forests from the Data BC website and buffered it to 50m as previously mentioned that mosquitoes can live farther from their preferred habitats to an extent. The total area calculated for old growth area with the 50m buffer was 169404441.145695 m². We combined the Old Growth layer with the soil drainage to make a layer called Terrestrial Union as it is the land based suitable potential habitat features for mosquitoes and the total area calculated was 290648279.695401 m².

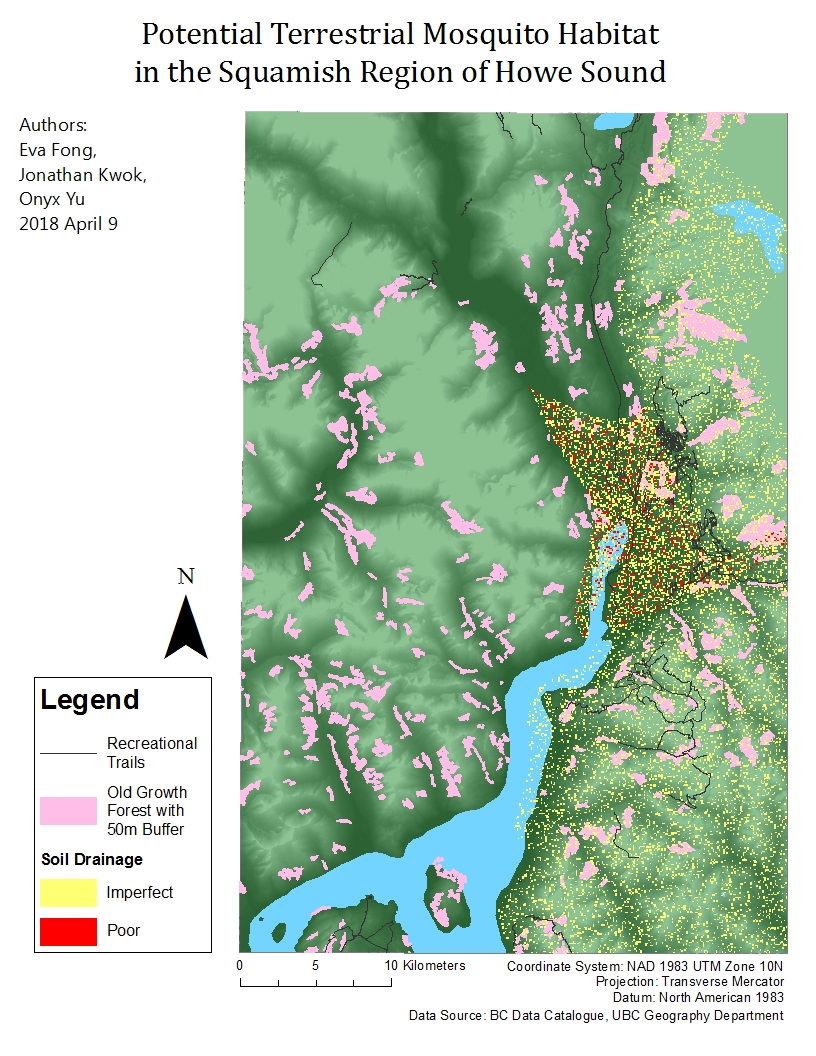

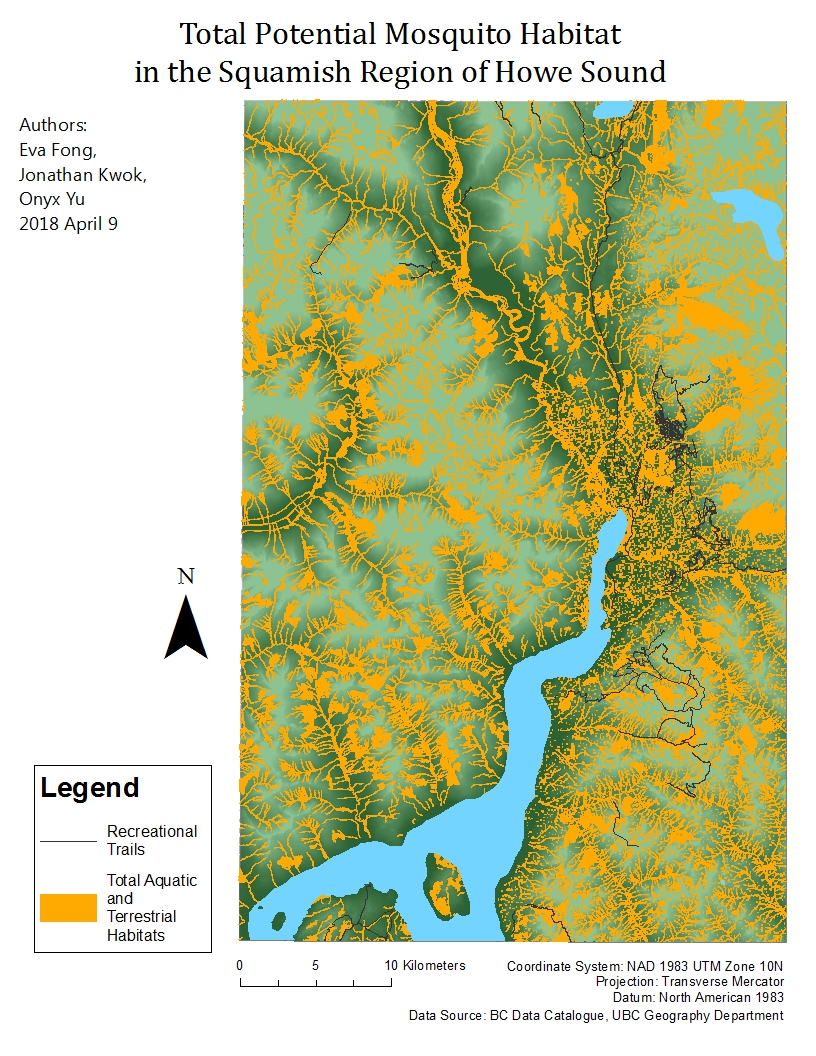

After figuring out and finding out the data for suitably potential climates for mosquitoes, we joined the water based and terrestrial based data together to make a probable layer union for where mosquitoes might possibly be inhabiting or found within the Squamish Valley region. The total area calculated for the probable habitat was 671733777.436648 m² as seen in Figure 1.3. However this is not the ideal habitat as it is either just suitable aquatic habitat or suitable terrestrial. So the final result in Figure 1.4 was a combined total area of aquatic and terrestrial with both aquatic and terrestrial layers joined, and the aquatic and terrestrial layers intersected. Based on the intersected layer, the ideal habitat for mosquitoes in the Squamish Valley Region is 80175027.189369 m².

Discussion

There seems to be a study bias towards disease-carrying mosquitoes, therefore almost all studies found on this topic were conducted in tropical and subtropical zones. This creates a gap of knowledge for local species of mosquitoes and their behavior. Almost all websites share similar information on mosquito behavior and habitat zones so it is assumed that all taxonomic groups share similar phenotypic and genetic qualities. As they are also a worldwide species, it is also assumed that they are generalist, therefore the information were based on papers that study mosquitoes on other continents. This will create some variance in our data.

Wind does play a role in mosquito population distribution since the species is based on flight for travel. However there was no information specifically on wind speed and its effect on mosquito population distribution. There are epidemiology papers that discuss the the spread of zika and malaria, but the effect of wind speed was not heavily discussed. However the map maintains its integrity in structural abiotic factors such as water availability and known breeding habitats, but adding data on wind speed and direction will affect source habitat locations.

A lack of accurate detail and focus on elevation might affect the accuracy of the spread of mosquitoes as there is a lack of abundance of mosquitoes in higher elevation possibly due to factors like a lack of moisture, high wind speed, lower temperature, and less tree coverage or leaf litter. There was also a lack of good resolution in our layers. The resolution was quite poor when zoomed in (100x100m) for certain layers so we couldn’t look at the minute details to determine which trails or trail sections even were considered ideal habitats for mosquitoes thus keeping the map and data at a regional scale.

It seems that temperature has a significant role in mosquito productivity, however most studies on mosquitoes were done in mediterranean climates or other climates where it is consistently warm year-round (Kikookar et al. 2017; Ngugi et al 2017). In British Columbia the maritime west coast climate varies in temperature and precipitation thus the presence of mosquitoes are only known in the warmest quarter of the year. With such limited time frame the rate of population growth is not entirely studied on the west coast. Especially with climate change, predictions of habitat change for mosquitoes are more difficult to calculate.

Since most studies were conducted in tropical and subtropical areas, this paper would highly benefit from more local study sites or study sites of equal climate variation. This would give us more information on the interactions with BC’s temperature and wind variation.

Studies of mosquito and their predators would also create additional habitat factors in our study. Our map is based on all potential habitat, but including known predator habitat and its population range would affect the presence of mosquitoes, possibly shrinking the net buffers and creating a specific niche.

Shifting from forested setting, it would be interesting to see how urban settings might play a role in mosquito habitat range. Urban environments could potentially open up habitat space since cities and towns have many still-water areas such as gutters and puddles. Cities are normally warmer in temperature relative to the surrounding environment, which is optimal for mosquitoes as well.

It would also be helpful to fill the gaps in our study if we had more detailed data for swamps or marshlands and see if that will affect the results of our study. Additional data on seasonal temperature would help fill the gaps of our study since that would increase the potential range of non-native mosquitoes and potential increase in mosquito population in BC, for example the summer season. The spread of diseases by mosquitoes can be derived to calculate the potential spread of mosquitoes.

Tables and Figures

Table 1.

Figure 1.1

Figure 1.2

Figure 1.3

Figure 1.4

Literature Cited

Belton, P. (1983). The mosquitoes of British Columbia. Victoria: The British Columbia Provincial Museum.

Dida, G. O., Anyona, D. N., Abuom, P. O., Akoko, D., Adoka, S. O., Matano, A. S., Owuor, P. O., and Ouma, C. (2018). Spatial distribution and habitat characterization of mosquito species during the dry season along the Mara River and its tributaries, in Kenya and Tanzania. Infectious Diseases of Poverty, 7(2), 1-16.

Hunt, S. K., Galatowitsch, M. L., and McIntosh, A. R. (2017). Interactive effects of land use, temperature, and predators determine native and invasive mosquito distributions. Freshwater Biology 62: 1564 – 577.

Johnston, N. T., Bird, S. A., Hogan, D. L., and MacIsaac, E. A. (2011). Mechanisms and source distances for the input of large woody debris to forested streams in British Columbia, Canada. Canadian Journal of Forest Research 41: 2231 – 2246.

Kikookar, S. H., Fazeli-Dinan, M., Azari-Hamidian, S., Mousavinasab, N., Aarabi, M., Ziapour, S. P., Esfandyari, Y., Enayati, A. (2017). Correlation between mosquito larval density and their habitat physicochemical characteristics in Mazandaran Province, northern Iran. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases 11(8): 1 – 19.

Mangudo, C., Aparicio, J. P., Rossi, G. C., and Gleiser, R. M. (2018). Tree hole mosquito species composition and relative abundances differ between urban and adjacent forest habitats in northwestern Argentina. Bulletin of Entomological Research 108(2): 203 – 212.

Ngugi, H. N., Mutuku, F. M., Ndenga, B. A., Musunzaji, P. S., Mbakaya, J. O., Aswani, P., Irungu, L. W., Mukoko, D., Vulule, J., Kitron, U., and LaBeaud, A. D. (2017). Characterization and productivity profiles of Aedes aegypti (L.) breeding habitats across rural and urban landscapes in western and coastal Kenya. Parasites & Vectors 10: 1 – 12.