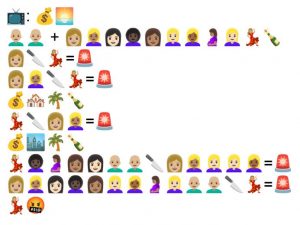

I am very curious to know if anyone is able to guess what show I am referring to!

Wow! I thought this was going to be easier to execute than it was, considering my frequent use of emoji’s when messaging with friends and colleagues!

- Did you rely more on syllables, words, ideas or a combination of all of them?

Interestingly, I ended up using emoji’s to reflect ideas and themes versus syllables or words. I believe this was because the emoji’s I had to choose from didn’t quite reflect the message I was hoping to convey. So instead of attempting to squeeze meaning out of a single emoji, I looked to grouping multiple emoji’s to convey a theme or idea. I also took this grouping and sequenced it to give more meaning and to provide a storyline. Struggling to make sure the emoji reflected what I was trying to say provided great insights into how these symbols, while carrying so much meaning, could lead to others misinterpreting, or not guessing correctly the story I am attempting to tell (Bolter, 2010). When you see an emoji symbol for a bag of money, this can have endless interpretations, leaving it up to the reader to make their best guess as to what the author is trying to say. Perhaps the saying “a picture is worth a thousand words” is misleading, as we don’t know which thousand words that picture could be referring to.

- Did you start with the title? Why? Why not?

I did in fact start with the title. I think that is the best way to identify a topic and to provide structure around the message being portrayed. However, beginning with the title and structuring the sequence from left to right, top to bottom, reflects how language shapes the way I think. While I share culture and language with many others, this has not afforded me the ease to interpreting my classmates emoji stories. As I read through my peers emoji stories, I struggled to decipher both the title and plot of a show, sometimes I could guess the title while not be able to interpret the plot, and so on. This goes to show that despite being from the same culture, we all have our own unique way of attaching meaning to the images we are seeing. reinforcing the notion that “picture elements extend over a broad range of meanings” (Bolter, 2010, p.59).

- Did you choose the work based on how easy it would be to visualize?

I would say no, I didn’t. I wanted to attempt to depict a show that others might find funny or be as into as I am. I thought I would do better at this since I generally use emoji’s to provide an emotional context to my prose/written text. Trying to depict relationships between people alongside big emotions, with only emoji’s, was incredibly difficult. That aspect of the activity really drove home the argument Bolter (2010) makes regarding “narrative power” being lost entirely from “picture writing” (p. 59).

- Breakout of the Visual

As I made my way through the readings this week (especially Bolter’s) I couldn’t help but wonder how Bolter’s perspective of what the breakout of the visual is would change if TikTok was thriving when this book was written. His book was published in 2010 and in 2016 TikTok made its debut. I cannot help but associate his idea of the visual breaking out to TikTok in all of its hypermediated glory. TikTok epitomizes the “hectic photomontage” (p. 51) that Bolter describes in hypermediated styles of prose. It does this by utilizing green screen features, allowing content creators to share multiple different images while speaking to what exists within those images, it also combines verbal and picture reading all the while listening to spoken words (Bolter, 2010). TikTok embodies the joining of “interactivity with the immediacy of a global hypertext” (Bolter, 2010, p. 70). Does TikTok improve the authenticity of content while providing immediacy for consumption of it? Can we determine if TikTok has remediated previous forms of social media and web pages?

References

Bolter, J. D. (2010). The breakout of the visual. In Writing space: Computers, hypertext, and the remediation of print (pp. 47-76). Routledge.