Published on: http://elpueblo.com.co/la-mujer-del-animal-esa-tan-nuestra-normalizacion-de-la-violencia

Amparo (Natalia Polo) takes one gnawed, almost eaten-away pen and writes on a similarly-looking notebook

My lord, what am I doing? What am I punished for?

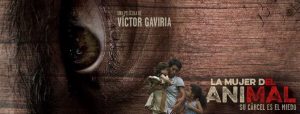

This turns out to be the only way the animal’s wife has to release her pain. This film, Victor Gaviria’s latest work, invokes the gender-based violence in a very graphic way which may lead those who do not often explore the inner dynamics of our national issues to agree with a religious explanation on why this woman suffers such a reprehensible and continuous treatment in most of the scenes in the film.

“She’s going through that situation because she’s a sinner. God has forsaken her.” This, although not expressed, may be what the neighbors and people who know her are thinking about her doom when they witness every single abuse she suffers. And even if she ends up believing that her tortuous life has been doomed by the creator (which is understandable, “nothing is worse than physical pain” said Winston Smith in 1984. Physical pain blurs thoughts) that is not the worst. What Gaviria shows in the film is how those who can stand up for her and stop this disgrace by taking decisive action wind up justifying that violence based on what they think is “divine intervention” which punishes “a bad wife, a bad woman”, or simply by behaving indifferently, the most subtle yet abject way.

The images in the film would claim the basis of the storyline is a sort of Tarantinesque ode to violence. Blood and flesh teem right in front of that audience which loves violence but shuns an analysis on its origin.

“The animal’s wife” is, no question, Gaviria’s most heartless, most graphic and, yes, most violent film of the four works he has directed.

Still, by handling the issue of gender-based abuse and violence with such graphic depiction does not intend to make it the core of the storytelling. Instead, Gaviria convincingly uses this resource to stand out that contrast when the tough punch the oppressor gives to victim, the blood flowing down her face, her screams out of helplessness and pain, meets the apathetic presence of those around, those who live in the outskirt of a city. In the age the film takes place, a massive group of forcefully displaced peasants is flooding the streets of Medellin.

By doing this, Gaviria seems to be asking: Would you also turn your backs? If you think this scene is repulsive, don’t you think is more hideous to justify or ignore the violence that scene portrays. Evil is clearly the main character, impersonated by

The Animal, but it is also revealed in such coward, or, perhaps, habituated, acceptance of the man’s personification of wickedness.

Those whose feelings are stirred by this succession of acts of explicit violence would do well if they check interviews, articles and essays on Gaviria’s work. The poet and director once stated that “I make films with the stuff others leave out: I work with stories regarding social issues and with what the actors of life have to say”. While recent Colombian cinema has mostly incorporated an intimate look on different dynamics with a strong European influence, Gaviria has broken his 13-year hiatus from Colombian film scenario with this film: bringing back a drama stand, he renounces long silences, subjective pauses, succinct and arty dialogues and establishes a rapid camera movement, a must when it comes to accurately registering the pitiless violence inflicted by The animal (Tito Alexander Gómez).

Similarly, as already used in his previous works, Gaviria allows a fluent, sincere dialogue, which greatly increases the drama portrayed in every scene of abuse. His expertise on working with natural actors (a trademark of his filmography) sheaths the story with tenable verisimilitude and sensitivity, as well as establishing a closer link between the audience and the story. Thus, the audience is asked to reflect on how similar they can be to those neighbors who watch the attacks on Amparo and ignore them.

There is a background on this story of humiliation, extreme misogyny but especially of criminal, conspiratorial and prevailing standardization of these hideous acts. A true Animal existed as a gangster in one of the outskirts of Medellin, and he really subdued Margarita (Amparo in the film) from 1975 to 1980. 4 years of research and two more of shooting were necessary to screen this 2-hour film, which Gaviria and the production company have taken to the TIFF, the Rome Film Festival and will be soon exhibited in FICCALI (CIFF – Cali International Film Festival). As expected, controversy will spark in the nation when it is massively released next January; we all know our tendency to hollow uproar.

This does not seem to affect Gaviria, who was present in the film’s exhibition at the most recent version of BIFF (Bogotá International Film Festival). He reaffirmed his conviction on revealing those stories underlying Medellin with its overpublicized development as well as other cities in the country where cinema seems to be fearful of doing the same: Exposing evil and its corresponding standardization.

Juan Merchán