Among educational institutions in contemporary developed countries, juku seem somewhat unusual in that they don’t appear to confer cultural capital, at least not in the classical sense that Bourdieu identified to be so important to class reproduction in Western Europe.

In Distinction Bourdieu proposed “cultural capital” as a helpful notion to understand intergenerational class-reproduction in postwar welfare states. If the state equalizes economic capital and safeguards workers’ rights and livelihoods to some extent, how come we still see intergenerational class reproduction, was the question he was addressing. One element in the answer was that education not only confers skills (human resources), but that it also confers prestige and subtle familiarity along class-lines that individuals can display (cash in on, to stay in the language of capital) at later stages. For example, highly-regarded secondary schools may not teach any content in a particular different way from any run-of-the-mill lycée, but students at these institutions (drawn largely from a class-homogeneous population) may be taught a curriculum that emphasizes highly-validated content or ways of talking about this content that distinguish graduates of such an institution.

{Note that this is obviously a very simplified and painfully simplistic version of Bourdieu’s concepts and their influence.}

High Cultural Capital in Juku?

While plenty of arguments can be made that cultural capital may be playing a different role in different cultural/national contexts and over time, this is one of the concepts that has clearly inspired a lot of research in the sociology of education over the past three decades or so.

Now, cultural capital and juku?

In their public and private self-representation, juku certainly don’t claim to be a place to acquire cultural capital, at least not of the high culture variety. Jukucho would immediately point to the predominance of standardized testing that would not make it possible for applicants (to higher education, to jobs, etc.) to display (and thus cash in) any cultural capital. There is also no evidence that juku attendance leads to lasting social ties of the kind that some secondary school and university clubs do (most famously baseball and rugby teams, for boys at least). This seems to be the case even though attendance at juku may stretch out over a much longer period (some time in elementary school through secondary education, and for some students on into higher education when they “return” to a juku as a teacher). So the immediate answer on (high) cultural capital would have to be, no, juku don’t seem to confer this.

Learning How to Learn

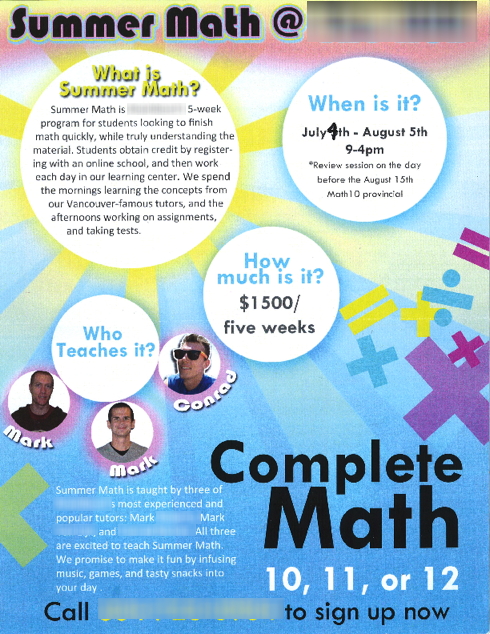

What about the kind of cultural capital that is more focused on study/learning skills. So, how to organize homework as opposed to knowledge of classical composers. Here, juku certainly claim that they are infusing students with cultural capital, specifically by teaching students how to learn. While the kind of learning that is being taught in juku with its focus on processing speed, correctness of answers selected from multiple choices, etc. is very particular, long-term attendance at a juku would certainly seem to reinforce this kind of cultural capital, and it is this kind of learning that may lead to greater chances at success at later stages in education that do in turn confer cultural capital, particularly the prestige associated with specific institutions of higher education. Takehiko Kariya (Oxford and 東大) has been arguing that learning capital is one of the crucial variables in Japanese stratification (see his Asia Pacific Memo for related arguments).

The Future of Cultural Capital in Juku

Juku will change in the future. From succession problems in small juku to a decrease in the competitiveness into higher education institutions due to the decline in the number of children, to some mild tendencies to broaden the access points to higher education, it seems like juku’s role may be declining in significance. Countervailing trends could be seen in the potential of juku to gain a more formal standing as alternative schools.

In terms of cultural capital, the greatest question may be whether juku will gain some kind of role as an arbiter of cultural capital. The current prominent role of three graduates of the Matsushita Seikei Juku in the Noda cabinet may be an example of such a role, though an exceptional one.

Another avenue for cultural capital to begin mattering more would be through a greater prevalence of admission to universities “by recommendation” rather than entrance examination. Perhaps some of the more well-known juku will gain the “right” to nominate students in the future?

Or, if students’ perception that the “real learning” occurs in juku gains in prominence, perhaps companies will begin hiring on the basis of which juku an individual attended?

This seems unlikely to me, but may be the case in the future.