0:30 I’ll be talking to you about language and I’ll be doing it using language of course because I can, this is one of these magical abilities that we humans have. We can plant ideas in each other’s minds.

This statement came early in the talk, and it really struck me. As an editor and designer, I’ve always understood that words matter, but I hadn’t quite framed it as “planting ideas in each other’s minds.” That metaphor makes the responsibility of language feel even more profound. In a 2025 hyper-connected & hyper-charged environment, where information spreads instantly and narratives shape public perception, the power of language feels even more crucial. It’s not just about communication—it’s about influence, cognition, and even shaping reality itself.

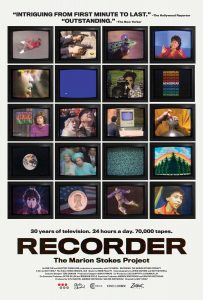

A documentary I saw recently, The Recorder: The Marion Stokes Project (2019) relates to Boroditsky’s idea of language as a tool for planting ideas in a fascinating way. Marion Stokes understood, perhaps better than most, how language and media shape public thought. By recording 24-hour news broadcasts for over 30 years, she created an archive that reveals how narratives are constructed, repeated, and evolve over time.

Her work connects directly to Boroditsky’s argument about the power of language. News media doesn’t just report events—it frames them, choosing which words, angles, and repetitions shape public understanding. In the digital age, where language moves faster and is more fragmented than ever, Stokes’ archive serves as a reminder that every phrase, headline, and soundbite contributes to the collective consciousness.

If language is planting ideas in minds, then media—especially 24-hour news—acts as a high-speed, industrial-scale planter. Stokes’ work fittingly raises questions about who controls that process and how language can be wielded for persuasion, misinformation, or truth.

27:10 In English you could say Cheney shot Whittington or you could say Whittington got shot by Cheney that removes Cheney a little bit out of it you could just say Whittington got shot leaving Cheney out of it all together.

Here Boroditsky points to the issue of language shaping perception, especially in reporting on powerful individuals in society and violence.

Boroditsky’s Cheney example highlights how subtle shifts in language can obscure responsibility. This plays out in news media constantly, especially in reporting on police actions. A CBC headline like “Investigation launched following video of man’s head hitting concrete during arrest” avoids directly stating who caused the injury. The passive construction—”man’s head hitting concrete”—implies an event that just happened, rather than one caused by police force. Meanwhile, the accompanying image clearly shows an officer kneeling aggressively on the man.

This linguistic framing isn’t neutral—it actively shapes public perception. By omitting or downplaying the subject (the police officer), responsibility is blurred, and the focus shifts to the outcome rather than the cause. This pattern is widespread in reporting on police violence, where headlines frequently use passive voice or indirect phrasing to reduce the perceived agency of law enforcement.

Boroditsky’s work reminds us that language isn’t just a tool for communication; it directs attention and assigns blame—or avoids doing so. Again, in an era of rapid media consumption, these subtle choices matter more than ever, influencing how readers interpret events before they even engage with the full story.

32:06 English speakers are still really strongly paying attention to who did it. They’re the ones who describe the action as “He popped the balloon, he broke the pencil,” but if you change the question and instead ask, “Do you remember if it was an accident?” Now it’s the English speakers who don’t look so hot. Now it’s the Spanish speakers who remember if it was an accident and the English speakers because they were paying so much attention to who did it and didn’t encode as strongly whether or not it was an accident so there’s a trade-off. There’s only so much stuff that we can pay attention to and what we see here are speakers of different languages witness exactly the same event but come away remembering different things about that event.

Here Boroditsky’s discussion of language shaping perception brought to mind the issue of eyewitness testimony, which is notoriously unreliable. As she explains, English speakers tend to focus on who performed an action rather than how it happened, whereas speakers of other languages, like Spanish, are more likely to remember whether it was intentional or accidental. This linguistic bias can have serious consequences, particularly in legal settings where eyewitness testimony plays a crucial role.

This Noba Project article highlights how memory is not a perfect recording but is reconstructed each time we recall an event. Factors like leading questions, biases, and even language structure influence what witnesses remember. If an English speaker is more likely to encode who committed an act but not whether it was accidental, their testimony might unintentionally skew toward assigning blame—potentially reinforcing biases in legal proceedings.

This underscores a critical issue in law enforcement and justice: the way we ask questions and frame events can shape not only how people describe their memories but also how they actually remember them. It raises ethical concerns about how police interrogations, courtroom questioning, and media coverage influence both perception and judgment.

Boroditsky’s research reminds us that language doesn’t just reflect reality—it actively constructs it. Understanding these biases is essential for developing fairer legal practices, improving eyewitness reliability, and recognizing the hidden ways language shapes our perception of truth.

39:02 They go to the store and they give money to someone and that person somehow magically knows how much money to give back and they just don’t know how they know. That it’s just this magical cognitive ability that other people have that they don’t have. For me, the way to think about it is that I have a lot of friends who are very good at improvising music or you know composing on the fly. I know they’re good because when they do it it sounds good, and if I tried to do that it would sound terrible. I have no idea how they do it, to me it’s this magical thing that they just open their mouth and it sounds good. I have no idea how they’re doing it, so that’s the way I think about this.You know that there’s something that you’re missing and you just have no idea how to get entry into that system. In this case what they’re missing is this cultural system of number words that was developed and refined over many many generations that we now take completely for granted because we learned it so long ago – we were kids we don’t remember learning it and yet it gave us entry into this whole world of numbers and math. And in our culture of course there’s nothing that’s created without math, there’s nothing in this room that was created without math.

Boroditsky’s description of feeling locked out of a system—knowing that something is happening but having no idea how—resonates with me profoundly. As a neurodivergent person, I often feel this way, as though there’s an invisible layer of knowledge or instinct that others access effortlessly while I struggle to find the entry point. Whether it’s unwritten social rules, professional networking, or even certain cultural expectations, there are moments where I know *something* is missing, but I don’t know what or how to bridge the gap.

This raises the unsettling question: How can we know what we don’t know? If entire systems—like math, language, or music—can be invisible to those who didn’t learn them naturally, what other cognitive frameworks exist that we might be unaware of? What skills, perspectives, or intuitions do others take for granted that remain mysteries to us?

For me, this connects deeply to neurodiversity. Many of the “missing” pieces aren’t intellectual but social, sensory, or contextual—things like intuiting unspoken expectations, navigating vague instructions, or interpreting shifting social dynamics. The challenge isn’t just access to knowledge; it’s access to the frameworks that organize and prioritize that knowledge in ways that make it usable.

Maybe the key isn’t finding every missing piece but recognizing that no one perceives everything. Just as neurotypical people might not realize how much of the world is designed around their default settings, neurodivergent people often notice gaps that others don’t see. Instead of endlessly searching for the missing puzzle piece, maybe the better question is: How do we build alternative entry points?

50:40 It is impossible to achieve exact translation across any two languages.

Boroditsky’s statement—“It is impossible to achieve exact translation across any two languages”—is a profound reminder that language is not a neutral vessel for meaning but a framework that shapes how we think. Words carry cultural, historical, and emotional weight that doesn’t always transfer cleanly between languages. Even within the same language, meaning shifts based on context, experience, and interpretation.

This connects directly to Bernard Shaw’s idea that the biggest communication problem is the illusion that it has taken place. We assume that because we’ve spoken—or written—our thoughts, others have understood them as intended. But language isn’t a direct pipeline of meaning; it’s an approximation, full of nuances, omissions, and assumptions.

This is especially relevant in education, workplace communication, and cross-cultural interactions. The words we choose may not land as we expect because they carry different connotations for different people. Neurodivergent individuals, for example, often experience this firsthand—what seems like a clear statement to one person might be confusing, overwhelming, or ambiguous to another.

If perfect translation is impossible, then perfect communication is, too. But that doesn’t mean we’re doomed to misunderstanding—it means we have to approach communication with more care. We need to ask clarifying questions, be open to reinterpretation, and recognize that language is only one part of understanding.

Instead of assuming communication has happened, we all should ask: Has it been received in the way I intended? And perhaps more importantly: What meaning might have been lost or transformed along the way?

56:46 Audience Q: Do you think that the different ways people use the language now by texting is changing the way they think?

Boroditsky’s A: It’s a wonderful question. So you know people are always using language in new ways, language has never been static. It’s a living thing. One thing that has been common throughout history is that older people complain about how younger people are killing the language and soon there will be no more language left because of the kids these days. People have worried about language being destroyed by all kinds of things, there were serious arguments that the invention of the printing press was going to destroy language. […] Teenagers in all generations were always about to destroy the English language, language continues changing and evolving and that’s its nature – it’s a living thing that we create. Whether it’s through technology or through being exposed to new experiences that’s just always going to happen. So yes people are definitely changing the language, part of that is driven by technology but this is nothing new.

Boroditsky’s response highlights a timeless tension in language evolution: the fear that change equals decline. As an editor, this reminds me of the divide between prescriptive and descriptive approaches to language. Prescriptivism adheres to strict traditional grammar and style rules, while descriptivism acknowledges that language is living and adapts to how people actually use it. The prescriptive approach often resists change, fearing that flexibility leads to degradation, but history shows that language has always evolved—through printing, radio, texting, and beyond.

For me, the biggest takeaway is how narrow and biased our understanding of the mind can be. If language shapes the way we think, then rigidly clinging to “correct” language might also mean limiting how we allow ourselves to think. Instead of only considering how the languages we speak shape the way others think, we should also ask: How do they shape the way I think? What biases, assumptions, or limits do I impose on my own thought processes because of my linguistic framework?

This realization presents an opportunity: How could I think differently? If language is always evolving, so is the way we construct meaning. Instead of fearing change, we can see it as an invitation—to challenge our perspectives, to rethink old structures, and to consciously shape the future of language rather than simply inherit it.