Franz Kafka

The Penal Colony

Much of the theory (and one short story) that we have been reading in the past weeks in one way or another has the body at the center, or better yet at an invisible, or displaced center, of its theoretical propositions. (This week’s reading of a Kafka story, The Penal Colony, is not an exception.) Body can be viewed in a few different forms, i.e. social body, body of works, individual body, etc., although it is usually exemplified in the individual body of the subject. The body as being inseparable from language, I would propose the body as the general grounds of human inquiry and discussion. This may be perhaps because the body is where we feel, it is what decays on its own through time, it is what will bring us to our end (death), and therefore it is the most important surface on which to make a semantic inscription and with which to make organizational strategies before each one meets that end. The latter concept, ‘organizational strategy’, now suggests a political aspect. This organizational aspect, as Louis Althuser has shown (calling it infrastructure), is inseparable or cannot survive or exist without semantic inscription, or the assigning of meaning; in Althuser this area belongs to an upper lever called the superstructure, this is where politics, an intangible, resides. The body is therefore ground zero for any type of social formation or organization. This for some probably would be difficult to accept if a position outside of the material is not taken; meaning if one does not take a stance outside of just the actual individual’s body starting with his or her skin. The body as the center, ground zero, goes beyond actual inscriptions on the skin, perhaps the widespread modern use of the ‘tattoo’ might suggest otherwise, but that is not what I intend to discuss here.

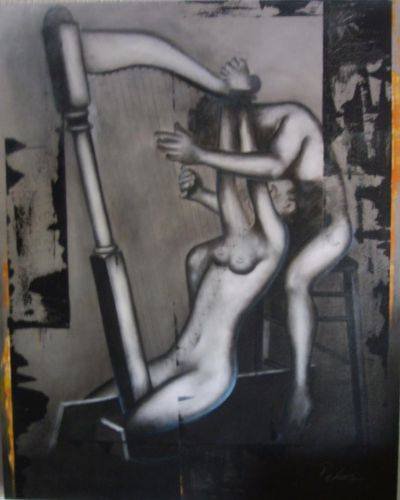

In Kafka’s story The Penal Colony the body is, as I have already implied, the center, the nucleus holding the language together in its organized form. In this case although, I don’t believe the body is part of the main question, it is rather part of the answer to that question. The question is: where is justice made? (It is a vague question I know.) This of course leads to a discourse on justice; asking what justice is. In the text although, there seems to be a working definition of what justice is. Justice in the text is simply punishing the guilty and in regards to this the text works with the notion that everyone is guilty; the officer and old commandant certainly seem to think so; explicitly at least. The traveler, although, doesn’t think that way. He thinks an accused needs a due process before justice is made. In the end both actually think the same. I will explain. The whole point of the apparatus is to kill. There is absolutely no point in a machine with such intricacies of writing on the body if the condemned is still going to die. That would be useful if the condemned were to stay living. In the end the Traveler stays living and there is a reason for that. The old has given way to the new. The whole process of the spectacle is no longer necessary; it has achieved the logical outcome of making justice by writing on the body. This outcome is to have those inscriptions present in every living body. That is to say, one is still guilty, but messages like “Honour your superiors” or “Be just!” are, as the Officer says, experienced in the body. The Traveler is the immediate example of a controlled, disciplined, civil body. He leaves the penal colony, but even outside he is imprisoned, he is still in the penal colony because the inscriptions in his body control him, control his body; because he, like everyone else, is guilty. The due process he believes in is applying by force onto the body of the condemned, i.e. fines (you have to work to pay the fine, right?), confinement, maybe death penalty, etc., bodily inscriptions which he or she did not accept or relieved themselves of them; so it actually is a reapplying of the inscriptions. Either way, justice has been made on his body. The ‘peculiar apparatus’ is the puppeteer.

Regarding Kafka and state power, do you really think that the author has completely given up on an individual conscience that can challenge authority? I see many instances of resistance in the text, and although the traveller disappoints us in the end, I think his decisions are not taken easily. It is almost as if he were wrestling with his conscience and loses. Kafka might be showing us that yes, we do have a choice; we can choose to obey the law, or we can choose to question it when it seems unjust.